Aviation History Through the Pages of FLYING

A look at nine decades of aviation innovation through our eyes.

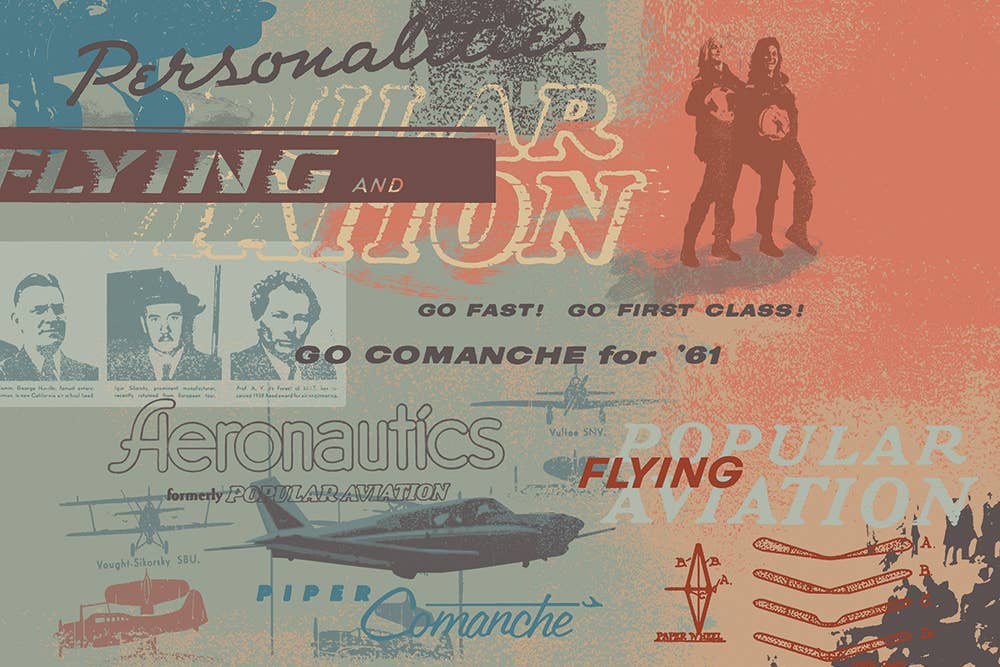

[Illustration by Clare Nicholas]

The 1920s: Popular Aviation Premieres

In August 1927, the first issue of Popular Aviation hit the newsstands, published by the Popular Aviation Publishing Company of Chicago.

The first cover featured three aircraft—two biplanes and a monoplane—in the sky. Below them, a crowd watches them fly over. Some of the people are standing on the roofs of buildings, others are climbing up a pole supporting a windsock, as if to get a better view of the airplanes. The monthly publication cost 25 cents, which equates to approximately $3.44 today.

The readers of Popular Aviation learned about the National Air Races (the Reno Air Races of the day), the fledgling airline industry, and the people and personalities who made up this new, exciting form of transportation and entertainment. The covers of the publication often featured artwork of the early airliners with happy, well-dressed passengers and pilots, who looked as if they were destined for adventure.

One of the first writers for the publication was General William Mitchell. Known as the father of the U.S. Air Force, Mitchell served with distinction in World War I and was promoted to brigadier general and assistant chief of the Air Service in 1921. When not writing articles about aviation adventures, he campaigned for the development of military aviation, as he felt that it would become critical in future wars. Mitchell encouraged military pilots to strive for record-setting flights and pushed for a transcontinental air race as a means to keep aviation in the public eye.

From the very first issue, there were advertisements for flight schools and pilot training programs promising big pay. Advertisements for careers in aviation touted the macho he-man image. Female pilots were a rarity. One of the first aviatrixes to appear in Popular Aviation was Dicky Heath, the daughter of E.B. Heath, the manufacturer of the Heath Parasol. At the time her photograph appeared in the magazine, Dicky Heath had logged approximately 300 hours flying Parasol Sport Airplanes.

Ziff understood that most people would read about aviation before they got anywhere near an airplane, so one of the first regular features of the magazine was Questions and Answers. Each issue also included plans for a model aircraft. At the time, model aircraft were scratch-built using paper and balsa wood.

By 1929, the magazine reportedly had a circulation of 100,000. In June of that year, the publishing company changed its name to Aeronautical Publications Inc., and the magazine became Aeronautics. Despite a notation on the cover that Aeronautics was formerly Popular Aviation, the change was confusing to readers, so the title was changed back to Popular Aviation in July 1930.

The 1930s: Adventure, Invention, and Colorful Covers

In the Great Depression, Popular Aviation continued to publish. The covers became more colorful, with a shift from traveling in airplanes to the aircraft themselves.

Air racing and epic, record-setting flights were still popular, as were profiles of famous aviators.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin—the inventor of the airships that bear his name—was featured. In the early 1930s, airships were the ocean liners of the sky. This changed on May 6, 1937, with the destruction of the Hindenburg near Lakehurst, New Jersey.

The pages of the magazine were heavy with advertisements for pilot training programs and aircraft that could be used by fledgling pilots.

There were lots of pilot reports on gliders. They were less expensive than motorized aircraft. There were also pages and pages of model aircraft designs.

The magazine recognized the founding of the Ninety-Nines, the international organization of women pilots in 1929, and the start of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) in 1939.

A young inventor named William Lear wrote about navigational equipment. Many years later, Lear would become famous for both his advances in avionics as well as the business jets he would design.

By the mid-1930s, the covers became more comic-book like, with bright, vibrant colors. American military pursuit aircraft (later known as fighters) began to appear. In 1935, the magazine published the plans for the Boeing Airplane Company's fastest low-wing pursuit airplane, the P-26. The plans for the models, just like the aircraft they depicted, became more detailed, with a list of necessary parts and their dimensions for the scale model.

The magazine continued to educate as pilots were introduced to air traffic control with the establishment in 1938 of the Civil Aeronautics Authority—the predecessor to the FAA. May 1939 saw the debut of I Learned About Flying From That. It became a favorite feature among readers. In the first installment, Garland Lincoln described running a Ford Tri-Motor out of gas in Alaska while in IFR conditions—after falling prey to “get-there-itis.”

The 1940s: Another Name Change, a Second War

The 1940s began with military aggression in the Pacific theater and Europe. The January 1940 issue trumpeted above the masthead: “More Allied-Nazi Warplane Photos!” Military training aircraft began to dominate the covers of the magazine. In the pages, readers learned about the airpower of combatant nations, and just about every advertisement encouraged young men to enter careers that would serve the national defense.

In January 1941, a cover featured entertainer Edgar Bergen and his ventriloquist dummy Charlie McCarthy, both dressed in flight suits and leather flying helmets. In the image, Bergen attempts to hand prop an aircraft while McCarthy, wearing an umbrella like a sidearm, looks on. The photo was publicity for the movie Look Who’s Laughing. Filmed in the spring of 1941, the movie featured Bergen, who really was a pilot, getting lost and landing at an airport in Wistful Vista. The plot revolved around the people of Wistful Vista attempting to get the owner of the Horton Aircraft Factory to buy their airstrip and set up a factory. The movie was released just weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Civilian pilots as well as lapsed pilots were called upon to do their part for their country, as AOPA joined forces with the magazine with a designated section in its pages—intent upon boosting airmanship.

In August 1940, the magazine was re-titled FLYING and Popular Aviation. Eventually, Popular Aviation was dropped from the title in 1942 (80 years ago).

As the war wound down, the message was clear—“flying is still the ‘everyman’ adventure.” A post-war aviation boom ignited, as aircraft manufacturers clamored to provide aircraft for all the former military pilots who weren’t ready to hang up their wings. By the end of the 1940s, readers of FLYING learned about a new type of aircraft called a jet, and swept-wing designs appeared.

The 1950s: Intro to Jets, Space, and Modern Problems

The civilian single-engine aircraft market swelled, and pilots were encouraged to go places they had never gone before. Aircraft that were introduced just before America entered the war—such as the Ercoupe and Call-Air—enjoyed new popularity.

The Korean conflict put military aircraft back on the cover. FLYING created special issues that celebrated aviation in each branch of the military.

The Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) was founded in 1953, and in October 1954, an experimental aircraft—the Horton Wingless, developed in 1952—appeared on the cover. The inventor, William Horton of Huntington Beach, California, claimed the aircraft was wingless because the entire body of the airframe was an airfoil.

Aviation became adventurous again as Max Conrad, who became known as the Flying Grandfather, set the first of several world records in light aircraft. He flew his PA-20-135 Pacer from Los Angeles, California, to New York, New York—setting a distance record of 2,462.335 miles.

The idea of using aircraft for commuting took hold, with a push to use them as tools to increase productivity—and FLYING launched a business aviation issue.

In 1957, Bernard Davis sold his share of the publishing company to Ziff, and left to found Davis Publications Inc.

By the end of the 1950s, America and Russia were entrenched in a game of nuclear brinkmanship. Articles about atomic weapons and the “space-race” appeared.

The 1960s: Living Faster, Going Farther

The 1960s dawned with American aviation satisfying a need for speed and distance. Jets were the commercial carrier of choice for many, and it seemed like everyone was in a hurry to get someplace.

General aviation pilots were also in a hurry, judging by the number of covers featuring light twins and retractable gear aircraft. FLYING began the year with a pilot report about the Bellanca 260, one of the first socalled “family-friendly airplanes.”

More retractable-gear airplanes appeared on the market and in the pages of FLYING. A multi-page spread introduced the Cessna Centurion, also known as the Cessna 210.

Aviation was becoming more technologically advanced as more ads appeared for aviation radios and avionics. The days of flying just with “altimeter needle, ball, and airspeed” were coming to an end.

FLYING branched out, writing for a more eclectic audience, to include stories about the air war in Vietnam and women in aviation. The publication recognized June as Discover Flying Month because it determined that many people would receive Discovery Flights as Father’s Day or graduation presents, and these would often lead to flying lessons. The airlines were hiring, and advertisements for flight schools and headsets for civilians became more prevalent.

In 1968, FLYING added two columnists to its staff, Richard Collins, who would become editor-in-chief in 1977, and Peter Garrison, who still contributes to the publication today.

The 1970s: Bax, Gas Shortages, and Airline Deregulation

Gordon Baxter, an aviator, radio personality, and humor writer from Texas, joined FLYING as a columnist. His shortest column appeared in 1973:

“Naked City Airport, Indiana. Turf strip overrun with parked cars of a crowd of 7,000 who came to view 50 naked girls vying for title of Miss Nude America, and four naked parachute jumpers. Unable to obtain other data, notebook was with my clothes.”

A fuel shortage marked the decade, and cars lined up for blocks at gas stations. The lack of available fuel—and the cost—got the attention of the aviation world.

FLYING featured covers with photos of GA and business aircraft. The only military covers during this decade were of the Canadian Snowbirds and vintage WWII-era designs, such as the deHavilland Spitfire and Fairey Firefly, Grumman Wildcat, and Vought Corsair. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 threw the airline industry into turmoil as it relieved the federal government of control over routes and fares. This resulted in new airlines, more flights, and more passengers. The pages of FLYING carried advertisements for programs for type ratings and accelerated ground schools. The airline world needed pilots, as those trained during WWII approached the mandatory retirement age of 60.

In 1971, cigarette advertising was banned on TV so the tobacco industry shifted to print—including FLYING. In 1975, the David Clark Company introduced the first noise-attenuating headset to address pilot hearing loss, now recognized as an occupational hazard.

FLYING featured several articles about finding a good, used airplane and aircraft restoration services.

Writer John W. Olcott noted that six out of 10 students dropped out because training was not enjoyable: “It’s going to hurt everyone from the airlines to airframe manufacturers if we don't fix it.”

In 1977, FLYING celebrated its 50th anniversary.

The 1980s: Space-Age Designs, GPS Debuts

The new decade began with a Long EZ on the cover. The aircraft, one of many space-age designs conceived by Burt Rutan, would prove to be very popular.

In 1986, Rutan’s twin-boom design, piloted by his brother, Dick Rutan, and pilot Jeana Yeager made the first nonstop, unrefueled flight around the world.

NASA’s space shuttle, America’s first reusable aircraft, became synonymous with the decade. Accomplished pilot J. Mac McClellan joined FLYING magazine and stayed for 35 years, serving for 20 years as editor-in-chief.

FLYING published its first guide for aircraft buyers. Fast airplanes are now what the public wants. The flying community recognized the V-tail Bonanza as the fastest single-engine piston.

In 1984, Ziff-Davis sold the magazine to Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S., then one of the world’s largest magazine publishers.

Civilians learned about a new form of navigation called the global positioning system (GPS). GPS approaches were introduced, and the children of the magenta line were born.

The 1990s: Women Military Pilots, Computerized Cockpits

With aviation still soaring high, the magazine featured stories about the first women to fill combat aviation roles in the U.S. military. The Navy, in particular, saw an increase in flight school applicants, thanks in part to the 1986 movie Top Gun, which boosted recruitment by 300 percent.

Aviation careers were still booming. Technical colleges ran ads showing off their courses in aircraft and avionics maintenance, air traffic control, and flying.

In the summer of 1995, FLYING marked the 50th anniversary of World War II. Contributing editor Russell Munson debuted in the issue with the P-51 Mustang on the cover.

The Cirrus SR20 appeared and set the aviation world alight with both the built-in airframe parachute and the Avidyne glass cockpit.

The concept of “fly by wire” and automation became more common.

The 2000s: 9/11, Glass, and LSAs

Aviation—like the rest of the world—wondered what Y2K would do to the computerized air traffic control system, and when the new century began with no major upsets, the world breathed a sigh of relief.

All of this changed on September 11, 2001, when airliners were used as weapons. The commercial aviation industry took a nosedive, and many people were afraid to fly. Congress created the Transportation Security Administration and airline travelers started taking off their shoes and leaving liquids outside a defined security zone.

People don’t particularly want to be packed into airliners when they have options such as fractionals and charters. The covers of FLYING reflected this, showing mostly business jets.

FLYING continued to educate up-and-coming pilots with articles on the basics, such as how to perform good takeoffs and landings, and techniques for instrument operations, such as flying a good nonprecision approach.

Email, in its infancy in the 1990s, clearly made it easier to send comments to the magazine.

In December 2003, pilots and aviation enthusiasts celebrated the 100th anniversary of aviation with an attempt to recreate the historic flight on December 17 at Kill Devil Hills with a replica aircraft. However, the weather didn't cooperate, with heavy winds and rain.

In July 2004, the FAA adopted the sport pilot rule. Very similar to a European ultralight certificate, the rule was ostensibly designed to make flying more affordable. In addition, pilots flying under the rule can do so with a driver’s license, in lieu of a medical certificate. Several aircraft manufacturers—among them Piper, Cirrus, and Cessna—developed and marketed light sport aircraft. Sport piloting appeared to stall in

2007, and FLYING columnist Richard Collins noted that the flood of aviation predicted by the sport pilot rule “hasn’t happened yet.”

Cub-inspired designs from CubCrafters and Legend Cub metaphorically duke it out at air shows. In June 2005, FLYING columnist Gordon Baxter passed away. We published his last column in September of that year.

The FAA raised the mandatory retirement age for airline pilots from 60 to 65, and the duration of a third-class medical, for those under age 40 at the time of examination, increased from 36 to 60 calendar months.

In 2008, a recession hit, and furloughs ravaged the aviation world. Everyone from airlines to flight schools, aircraft manufacturers, and aviation publications felt the bite, as once-healthy aircraft order books fell off in the wake of the economic crunch.

FLYING columnist and editor J. Mac McClellan told readers about something new to improve aircraft safety called ADS-B. It would take the industry more than a decade—and a mandate from the FAA—to compel aircraft owners and operators to install the lifesaving equipment into GA aircraft across the spectrum.

In June 2009, FLYING was sold to Bonnier Corp., the U.S. magazine division of the family-owned Bonnier Group of Sweden. The acquisition placed the magazine in a portfolio aimed at active enthusiasts of a wide range of activities that pilots might also be drawn to.

The 2010s: Pilot Shortage and Training Boom

As the new century turned the corner on a new decade, aircraft manufacturers, many of whom were forced to layoff staff and cut back production, expressed optimism that they would recover—eventually.

The airlines were in a hiring frenzy. The pilot shortage was very real and began at the flight school level, because when CFIs reached 1,000 hours total time, they were off to the regional airlines. There was more talk about ADS-B as a means for making flying safer— but there was also some pushback from aircraft owners, who balked at the installation cost, which ran north of $2,000.

FLYING supported the promotion of learning to fly with special issues. A slew of entry-level aircraft debuted under the light sport category, with the Icon A5, and models from Pipistrel, Flight Design, and Tecnam.

The FAA introduced the remote pilot certificate in 2016. There were growing pains, though, as actively

piloted aircraft and small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS) learned to share the sky.

The 2020s: ...And Here We Are

The COVID-19 pandemic and climate change were the buzz phrases as FLYING entered the new decade. The death toll from the virus has been like nothing seen in several generations.

Airliners were parked for more than a year; thousands of people were furloughed. CFIs who barely made enough to survive were wondering if they should risk their health and the health of their families to build hours for a job that may not be there in a few short months.

A vaccine was developed and slowly the world—and aviation—emerged from the global timeout. The airlines added back flights, and flight schools ramped up.

General aviation has proven resilient through the crisis, with business aviation taking on some of the activity lost by the airlines. People who discovered flying during the pandemic now find they don't want to return to crowded hub airports and security lines.

In 2021, Bonnier sold FLYING to digital media entrepreneur Craig Fuller, and the new FLYING was born.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox