A Formation of Dissimilar Aircraft Unravels

Pilots are endowed with the right to take risks.

A contributing factor, the NTSB said, was “the stepped-down configuration of the formation flight which was composed of dissimilar aircraft.” NTSB

On a Saturday morning in April 2017, a swarm of airplanes—40 pilots attended the preflight briefing—took off from Spruce Creek Airport in Florida for a flight to nearby Titusville to attend an EAA pancake breakfast. The Saturday morning breakfast flight to various destinations is a tradition at the private airstrip, the centerpiece of a gated community with a population of several thousand residents and hundreds of airplanes.

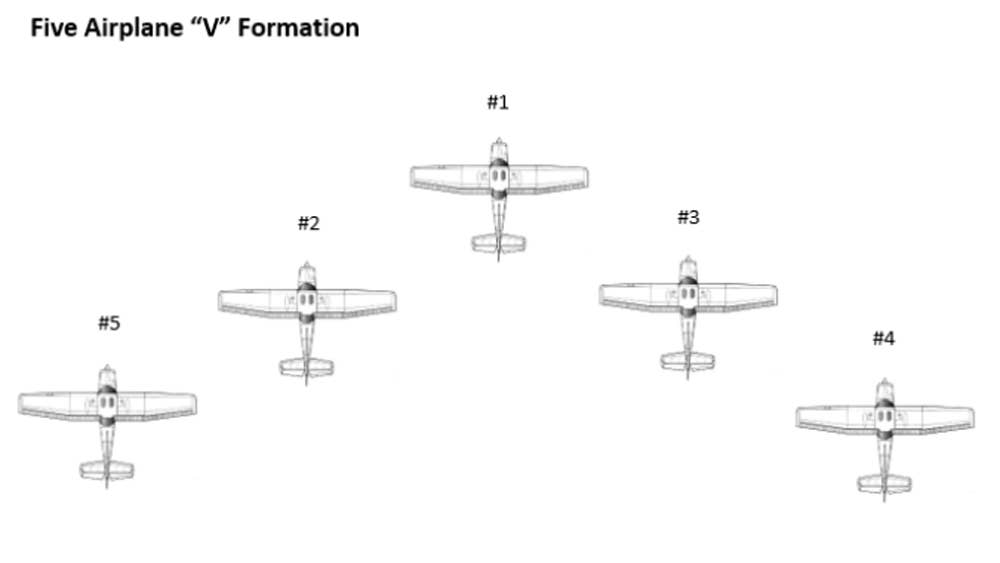

According to the National Transportation Safety Board’s report, one group of five airplanes made up a “wide, loose” V-formation, which one pilot said “was normal for en route.” In the lead was a Great Lakes biplane. Behind it to the right was a Cessna 170, and behind the Cessna was a Grumman Lynx, originally the Bede-designed two-seat American Yankee.

On the left side of the V was a Grumman Tiger, and behind and to the left of the Tiger was a Decathlon.

The formation assembled on the way to 1,000 feet and turned southward toward Titusville. The morning sun—20 degrees above the horizon—was to the left and in the eyes of the pilots on the right side of the formation, who needed to look left to hold position. The flight lead ordered a change to a left echelon formation, in which all five airplanes would form a staggered line to the lead’s left. All would then be looking to the right, away from the sun.

In principle, a formation consists of “elements” of two airplanes, or sometimes one. The Great Lakes and Tiger were the first element in the formation; the two airplanes to the right of the Great Lakes formed the second element and as such would move into place together between the Tiger and the Decathlon, which constituted a third element. The Decathlon would first drop back along the diagonal line of the left side of the V to open up space. The second element would then shift laterally behind the lead, dropping down slightly to pass below the lead’s wake. The 170 would take up a position behind and to the left of the Tiger, and the Lynx would continue sliding sideways, passing behind the 170 and lining up behind it to its left. Finally, the Decathlon would tuck in to complete the evenly spaced echelon. During this maneuver, the 170 would fly by reference to the Tiger, the Lynx by reference to the 170 and the Decathlon by reference to the Lynx.

Something went wrong.

Moments after he commanded the shift from the V to echelon formation, the flight leader saw a “flash.” He immediately pulled up and out of the formation. To the Lynx pilot, the transition appeared “slow and normal” until he saw parts and vapor fly past him. He then saw the Tiger pitching up, appearing to “be past vertical…almost like it was in a loop.” The right wing of the Cessna appeared to fold upward, and its tail swung to the left. He saw the flight leader pull up, and he himself banked steeply to the left, out of the formation.

Witnesses on the ground reported that both the 170 and the Tiger fell vertically to the ground. The flight leader saw the 170 descend “like a falling-leaf maneuver,” its right wing appearing “folded over.”

Examination of the wreckage of the two airplanes revealed that the 170 had come up beneath the Tiger, whose propeller had severed the Cessna’s right flap tracks, the inboard end of its right aileron and its aileron cables. The wing had remained in place; it was the dangling flap that made it appear to witnesses as if the wing had folded over. The empennage and the portion of the tail cone to which it was attached had completely separated, however, and were attached to the airplane only by control cables, which were twisted around one another multiple times. The wreckage of the Tiger was also badly mutilated, but the only damage that definitely occurred during the collision was gouges in the propeller blades made by the Cessna’s aileron control cables.

The pilots of both airplanes were ATPs and instructors with over 10,000 hours and multiple ratings and type ratings. Both were airline pilots.

The NTSB attributed the accident to “the Cessna pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from the Grumman...” A contributing factor, the NTSB said, was “the stepped-down configuration of the formation flight which was composed of dissimilar aircraft.”

That the Cessna pilot had failed to remain clear of the Tiger was indisputable. Why the NTSB thought it happened was more difficult to understand, but the reference to a “stepped-down configuration” of “dissimilar aircraft” gives a hint. “Dissimilar” means a mix of high-wing and low-wing aircraft. The pilots of military airplanes sit high, surrounded by a transparent canopy or greenhouse; a civilian pilot’s view is obstructed by wings, the cabin roof and window frames. The NTSB evidently thought that mixing types increased the likelihood of creating complementary blind spots.

The crossover from right to left required the 170 to drop down a little to avoid the wake of the leader. I suspect the 170 pilot lowered his nose slightly and kept the Great Lakes in view as he crossed. He reduced power at the same time, so as not to gain speed. However, he did not accurately balance pitch and power in such a way as to drift backward, and his own high wing blocked his view of the Tiger, while the Tiger’s low wing blocked its pilot’s view of him. In the event, he came up below and ahead of the Tiger, whose propeller sliced into his right wing from above.

Did the pilot of the Tiger see anything before the collision? Probably—the Cessna’s nose was well ahead of the Tiger’s. The Tiger’s nearly vertical pullup may have been an instinctive reaction to a peripheral glimpse of white below and to the left. The NTSB report makes no judgment as to whether the Tiger remained controllable after the collision; possibly, it stalled and spun after the pullup, and the pilot failed to recover because of the low altitude.

Formation flying is a recreational activity that many pilots enjoy. During the 1990s, efforts to ensure the safety of formation flying led the T-34 Association to create its own Formation Flight Manual, which was eventually adopted by a number of other organizations in the warbird community. Eventually, a system of education, training and certification of formation pilots—particularly intended to qualify pilots to participate in airshows—came into being.

Formation flying was regularly practiced at Spruce Creek under the rubric of the informal Gaggle Flight Formation Group. Some pilots in the group had formation certification, some didn’t—it was not required. When new, uncertified pilots joined, group members “would keep them at a distance” until their abilities became apparent. The NTSB seems to have taken a dim view of the “Gaggle Flight” formation manual, which is a simplified and lighter-hearted version of the original T-34 Association document. The manual, the NTSB complained, “did not reveal any evidence of a structured program that provided standards for formation training and flying, a system for proficiency evaluation, a method for monitoring currency, or any formation-standards evaluation guides or forms.” It also cited an FAA advisory circular, AC 90-48D, that cautioned formation pilots to “recognize the high statistical probability of their involvement in midair collisions.”

According to an article that appeared in the Daytona Beach News-Journal after the release of the final NTSB report in September 2019, a Spruce Creek spokesperson conceded that formation flying was riskier than other types of flying but denied that it was “probable” that it would lead to a midair collision. The NTSB’s members, he said, “don’t like the freedom” of the Gaggle’s lack of strict standards. Nevertheless, he acknowledged the crash had led some residents, including him, “to rethink whether they’re willing to take the additional risk that accompanies formation flight.”

“I think a lot of folks kind of stepped back from it a bit,” he said.

This story appeared in the March 2020 issue of Flying Magazine

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox