An Unqualified Pilot—But Not Disqualified

Several colleagues knew of a pilot’s limitations before a fatal 767 accident.

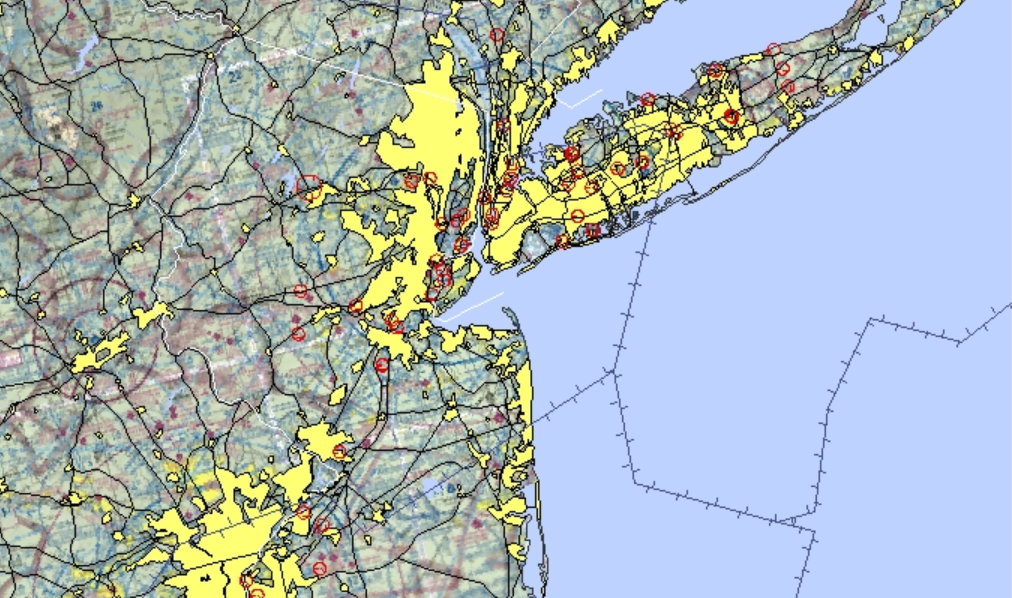

“One instructor thought he merely ‘had a confidence problem.’ Another, less charitable, called him a ‘train wreck.’ “ Courtesy YMP

In February 2019, a Boeing 767 freighter arriving from Miami was approaching George Bush Intercontinental in Houston. Forty miles from the airport, as it crossed the shoreline at 6,000 feet, the jet suddenly pitched down. In a 45-degree dive, it plunged into Trinity Bay with an airspeed of 434 knots and a descent rate of almost 13,000 feet per minute. The three airmen aboard, two flying pilots and a deadheading third, died; scraps of the shattered airplane and its cargo were scattered over a mile of shallow water.

The black boxes were recovered, and the National Transportation Safety Board was not long in explaining the bizarre event.

A few seconds before the start of the dive, the airplane, which was flying on autopilot and autothrottles, had shifted into go-around mode, adding power and pitching up. The first officer, who was the pilot flying, was taken by surprise; he believed the airplane was stalling and pushed it over into a dive. Bafflement, confusion and panic reigned in the cockpit. A few seconds before impact, when the airplane emerged from the 3,000-foot cloud deck and its attitude became apparent, both pilots hauled back on the control column in an effort to recover, but it was too late. The 767, pulling 4 Gs, was still 16 degrees nose down when it struck the water.

The cockpit voice recorder stored those final chaotic seconds.

CAM: Cockpit-area microphone.

CAP: Captain.

FO: First officer.

JMP: Deadheading jumpseat pilot.

Times are Central Standard Time. Utterances that were exclaimed or shouted are indicated with exclamation points.

12:38:31.1

CAM: (A faint click is heard; it is thought to be the movement of the go-around switch.)

12:38:43.6

FO: Oh...whoa! Where’s my speed? My speed!

12:38:48.0

FO: We’re stalling! Stall! Oh, Lord, have mercy [on] myself! Lord, have mercy!

(About 12:38:55, the 767 emerges from the cloud deck into the clear.)

FO: [Calls out captain’s name]

CAP: What’s goin’ on!?

FO: Lord. [Calls out captain’s name]

JMP: What’s goin’ on!?

FO: [Calls out captain’s name]

JMP: Pull up!

FO: Ah! Oh, God!

12:39:02.0

FO: Lord, you have my soul!

The recording ends at 12:39:03.9.

The NTSB’s theory of the case was that the airplane, which was passing through the leading edge of a cold front, was in IMC and light chop. The FO—44 years old, and a 5,000-hour ATP with multiple type ratings—was the pilot flying. The captain, 60, was preoccupied with programming the flight-management computer and communicating with Houston.

Most likely, the FO, without realizing it, touched the go-around-mode switch with his wrist while his hand was resting on the speed-brake handle. The captain was expecting the descending airplane to level out at 3,000 feet, and so would not have been surprised by the initial change in power and vertical acceleration associated with the actuation of the go-around mode. But the uncommanded pitch-up and acceleration, the board thought, created in the FO a so-called somatogravic illusion—a class of spatial disorientation in which longitudinal acceleration makes a pilot feel that the airplane’s attitude is more nose-up than it actually is. The illusion—which stems from the impossibility of subjectively distinguishing between the perceived force of gravity and longitudinal acceleration attributed to engine thrust—can be surprisingly powerful. According to the NTSB’s analysis, during parts of the dive, while the airplane was still in cloud, the crew’s subjective impression could have been of a nearly vertical climb.

What happened next, however, was extreme and unexpected. In the grip of an irrational startle response, the FO jumped to the conclusion that the airplane was inexplicably pitching up and in danger of stalling, and he responded by pushing hard forward on the control column. Needless to say, this is not the recommended procedure for stall recovery in a 767—not that there was any indication of a stall or an impending stall, other than the FO’s subjective sensations.

In effect, the FO lost his mind—his pilot mind, that is. The one that takes in the situation, weighs the probabilities, scans the instruments, and gets a grip on itself before acting.

The NTSB found in the FO’s history some hints of how his wildly inappropriate reaction came about. He had been employed by a number of airlines and had failed to advance from FO to captain. He had repeatedly resigned rather than face failure and had concealed some of his previous unsuccessful employments from subsequent employers. He had experienced many difficulties in training, but he eventually passed oral and practical checks by dint of those brief periods of competence that often follow an intense training session but are soon lost. If he didn’t pass, he resigned in order to save face. Between disasters, however, he had had periods of adequate performance, and he seemed to be unaware of, and refused to acknowledge, his own shortcomings.

His particular weakness was a chronic inability to respond methodically and appropriately to unexpected events. One instructor thought he merely “had a confidence problem.” Another, less charitable, called him a “train wreck.” One noted that he was very nervous and lacked situational awareness. When he became aware that something needed to be done, he often did something inappropriate.

The board found fault with the captain’s failure to intervene more quickly, but it’s not hard to imagine that he did all he could, given the kamikaze dive into which the FO had put the airplane, as well as the short time he had to diagnose an unimaginable situation and react to it.

The NTSB included the FAA among the contributing factors in this accident. If the agency had acted sooner, the board wrote, to implement the electronic pilot-records database that Congress ordered it to create in 2010, the FO’s shortcomings would have been discoverable by potential employers. As it was, the still-prevalent manual system for retrieving information about pilots’ employment and performance histories remains cumbersome, haphazard and easily gamed.

Many pilots won’t welcome a system of federal surveillance that will make every bad day in the simulator or thorny experience with a check pilot available to future employers. However, as several board members pointed out in concurring statements, the military services have no trouble washing out poorly performing candidates, and it is perhaps better to disappoint a few than for lives to be lost because of grotesque and predictable failures of airmanship.

Which Way Is Up?

Two components of this accident stand out: the “somatogravic illusion” and the system of hiring, testing and record-keeping that can put an obviously unqualified pilot into the cockpit of an airliner.

The NTSB cited many instances of pilots with well-documented weaknesses who eventually became responsible for a crash. Several members mentioned the 2009 Colgan Air accident near Buffalo, New York, where the captain misinterpreted a correct action by the automatic flight-control system and reacted by stalling the airplane and holding it in the stall all the way to the ground.

As to the somatogravic illusion—the word comes from the Greek soma, meaning “body,” as in somatic symptoms—it has been held responsible for many crashes in which a pilot taking off in darkness over water or unlighted terrain descends under control in the belief that the airplane is climbing. Burke Lakefront Airport in Cleveland has seen at least three such accidents. The importance of relying on instruments, not sensory cues, and maintaining a positive rate of climb after takeoff is obvious to everyone, and yet, this class of accident continues to occur.

This story appeared in the November 2020, Buyers Guide issue of Flying Magazine

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox