Ask FLYING: What is a G-AIRMET?

An aviation meteorologist explains how a graphical AIRMET is different from a traditional one.

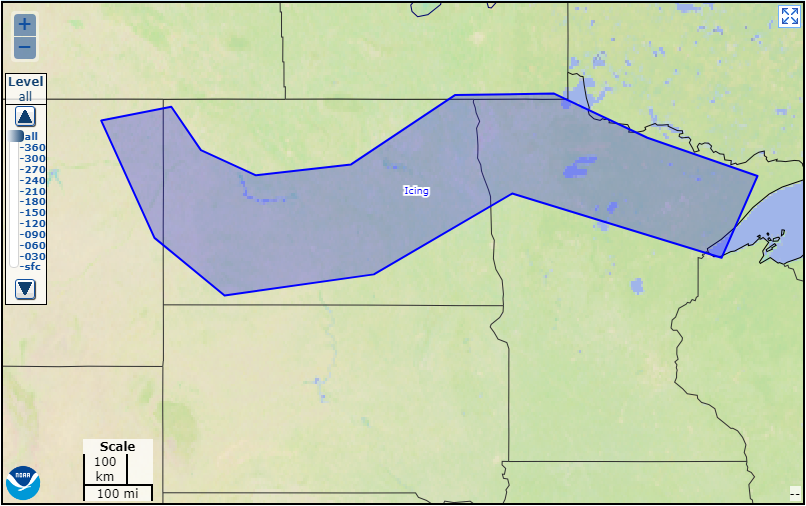

The relatively new G-AIRMET format gives a snapshot of forecast hazardous conditions. [Courtesy: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration]

Q. What is a ‘G-AIRMET’ and how is it different from an AIRMET?

A. It has been more than a decade since the Graphical AIRMET [AIRman's METeorological Information] or G-AIRMET replaced the legacy AIRMET. However, it seems that on various podcasts, webinars, and social media platforms, pilots are still clinging to the term "AIRMET.” Perhaps it's because they were never told that on March 16, 2010, the G-AIRMET became the operational product for pilots and replaced the existing textual AIRMET. After standardizing the language for the AIRMET text in 2006, the legacy AIRMET is now a byproduct of the G-AIRMET, and unfortunately, has stuck around for more than a decade for a variety of reasons. Moreover, many of the heavyweight EFBs continue to cling to the legacy AIRMETs in their app.

At this point in time, all pilots should have moved away from the legacy AIRMET in favor of using the G-AIRMET. In fact, if you search on the Aviation Weather Center (AWC) website (https://aviationweather.gov), you will not find a graphical depiction of the legacy AIRMET. Yes, the AWC does provide access to the text associated with the latest AIRMETs, but does not depict them graphically. Well, that's not entirely true. It's there if you know the "secret" URL, but it's not part of the site menu structure. That was done on purpose to force pilots to use the new product.

To answer the reader’s question, we need to do a quick history lesson. The legacy AIRMET has always been a textual product. That is, before sophisticated computer systems were in place, an aviation meteorologist issued an AIRMET solely using a keyboard to type in the forecast one character at a time. And, during those days when a pilot received a route briefing from Flight Service, the pilot pulled out a blank advisory plotting map to draw the various AIRMETs as polygons that the briefer provided. Those days of drawing polygons by hand are long gone. When the internet became alive with aviation weather guidance, websites began plotting these polygons for pilots based on the VOR line referenced in the header of the textual AIRMET.

The main issue with the legacy AIRMET is that it’s a time-smeared forecast valid over six hours. Its temporal resolution long became a running joke for many pilots who said that most AIRMETs were useless. That’s an understandable reaction since the AIRMET had to cover a period lasting six hours—what if an area of weather was moving quickly through the Midwest? Well, it had to account for that movement within the valid period and the AIRMET ended up covering a lot more real estate because of the time-smear nature of the product. Consequently, at any point in time, some parts of the AIRMET region did not contain the adverse weather identified in the AIRMET. This is why now, in the digital age, we’ve moved away from the AIRMET and today use G-AIRMETs.

Even though the legacy AIRMET still gets issued four times a day, the primary difference is that a G-AIRMET is a "snapshot" of a particular hazard valid at a specific time (e.g., 0300Z), whereas the legacy AIRMET is valid over six hours. The difference is that the G-AIRMET depicts the expected coverage of adverse weather valid at a particular time within an area defined by a forecaster-generated polygon. Typically, this region is much smaller, and therefore, more useful to the pilot. In the end, the G-AIRMET provides a much better spatiotemporal resolution of the weather hazards than the legacy AIRMET.

In the case of G-AIRMETs, you will notice there's no textual component like the legacy AIRMET. Instead, G-AIRMETs are created by aviation meteorologists by a simple point and click on a screen. Therefore, it is strictly graphical, although it does include some metadata. For G-AIRMETs depicting widespread moderate ice, for example, the metadata simply consists of upper and lower altitude limits of the airframe icing threat. A G-AIRMET for IFR conditions will include metadata for the specific cause of those IFR conditions such as PCPN (precipitation), BR (mist), or FG (fog).

To cover the same 12-hour period as the legacy AIRMET, each forecast cycle for G-AIRMETs consists of five snapshots. This includes an initial snapshot and snapshots with a lead time of 3, 6, 9, and 12 hours. Then, once the forecaster has defined the snapshots, the software automatically generates the legacy AIRMET text by taking the union of the first three snapshots (initial, 3-hour, and 6-hour). Then the AIRMET outlook is a union of the last three snapshots (6-hour, 9-hour, and 12-hour). What you end up with is guidance with better spatiotemporal resolution.

For example, above are two legacy AIRMETs for airframe icing valid from 15Z to 21Z with the text for each one shown below. This consists of a tiny AIRMET in eastern Montana and a larger one to the east in North Dakota and Minnesota. Why not just combine the two? Given that the legacy AIRMETs must be issued based on the aviation area forecast (FA) boundaries (remember those?), the AIRMET must be split into two parts, namely, for the Chicago and Salt Lake City FA areas.

On the other hand, G-AIRMETs are essentially seamless and don’t need to obey the FA boundaries. Shown below are the three G-AIRMET snapshots that define the initial (15Z), 3-hour (18Z), and 6-hour (21Z) forecasts. For the most part, the union of these three snapshots should approximate the legacy AIRMET area.

[Courtesy: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration]

If you were departing out of the Dickinson/Theodore Roosevelt Regional Airport (KDIK) in southwestern North Dakota around 21Z, it would appear from the legacy AIRMET that moderate airframe icing might be an issue. However, at 21Z, the only region of moderate airframe ice forecast using the G-AIRMET snapshot valid at 21Z is located at the northern border between North Dakota and Minnesota.

But there's another advantage of the G-AIRMET. The legacy AIRMET was split into three groups, namely, Sierra, Tango, and Zulu for mountain obscuration and IFR conditions, turbulence, and icing, respectively. The problem is that each one of these had embedded subcategories. That is, AIRMET Tango was issued for moderate nonconvective turbulence, nonconvective low-level wind shear (LLWS), and strong surface winds. Now, those three are split out into their own G-AIRMET making it easier to recognize.

For example, the G-AIRMET above was issued for non-convective LLWS. It is valid at 0300Z. When you look at the AIRMET text below, it'll be buried in AIRMET Tango with potentially an AIRMET for moderate turbulence and one for strong surface winds, as it was in this case. So, it's easy to get lost in the shuffle as you can see below.

WAUS42 KKCI 292045

MIAT WA 292045

AIRMET TANGO UPDT 5 FOR TURB STG WNDS AND LLWS VALID UNTIL 300300

AIRMET STG SFC WNDS...NC SC GA FL AND CSTL WTRS

FROM 130E ECG TO 190ESE ECG TO 130SSE ILM TO 200ENE PBI TO 60NE

PBI TO 30NNW TRV TO 20S CRG TO 20W SAV TO 40SSE ECG TO 130E ECG

SUSTAINED SURFACE WINDS GTR THAN 30KT EXP. CONDS CONTG BYD 03Z

THRU 09Z.

LLWS POTENTIAL...NC SC GA FL AND CSTL WTRS

BOUNDED BY 30ESE CLT-40NNW ILM-20SSE ILM-CHS-20NE CRG-20SSW OMN-

50SE CTY-20WSW AMG-30ESE CLT

LLWS EXP. CONDS DVLPG 00-03Z. CONDS CONTG BYD 03Z THRU 09Z.

OTLK VALID 0300-0900Z

AREA 1...TURB NC SC GA FL WV MD VA AND CSTL WTRS

BOUNDED BY 30SSE CSN-150SE SIE-190ESE ECG-150ESE ILM-90S ECG-

40SSE CLT-40S IRQ-40ENE CTY-20SSW TRV-40ESE RSW-40WSW SRQ-40SW

TLH-20SE LGC-50SSW VXV-40E BKW-30SSE CSN

MOD TURB BLW 100. CONDS CONTG THRU 09Z.

AREA 2...TURB NC SC GA FL ME NH VT MA RI CT NY LO NJ PA OH LE WV

MD DC DE VA AND CSTL WTRS

BOUNDED BY 40ESE HUL-160ESE ACK-120S ACK-160SE SIE-190ESE ECG-

130SSE ILM-50SSE FLO-160ENE PBI-60ENE PBI-20WNW ORL-30E ATL-30SW

VXV-HMV-HNN-40E CVG-30W APE-50S YOW-40ESE HUL

MOD TURB BTN FL180 AND FL450. CONDS CONTG THRU 09Z.

To avoid this kind of confusion, start using the term G-AIRMET unless you are specifically referring to the time-smeared legacy product. Just like the termination of the aviation area forecast (FA) on October 17, 2017, the legacy AIRMET is on the chopping block and will someday just magically disappear. I hear that might be sometime in 2023 but there has been no formal messaging from the FAA or NWS as of yet.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox