Auto Flight for Rotorcraft

Garmin’s new autopilot for the AStar smoothes out the rough edges.

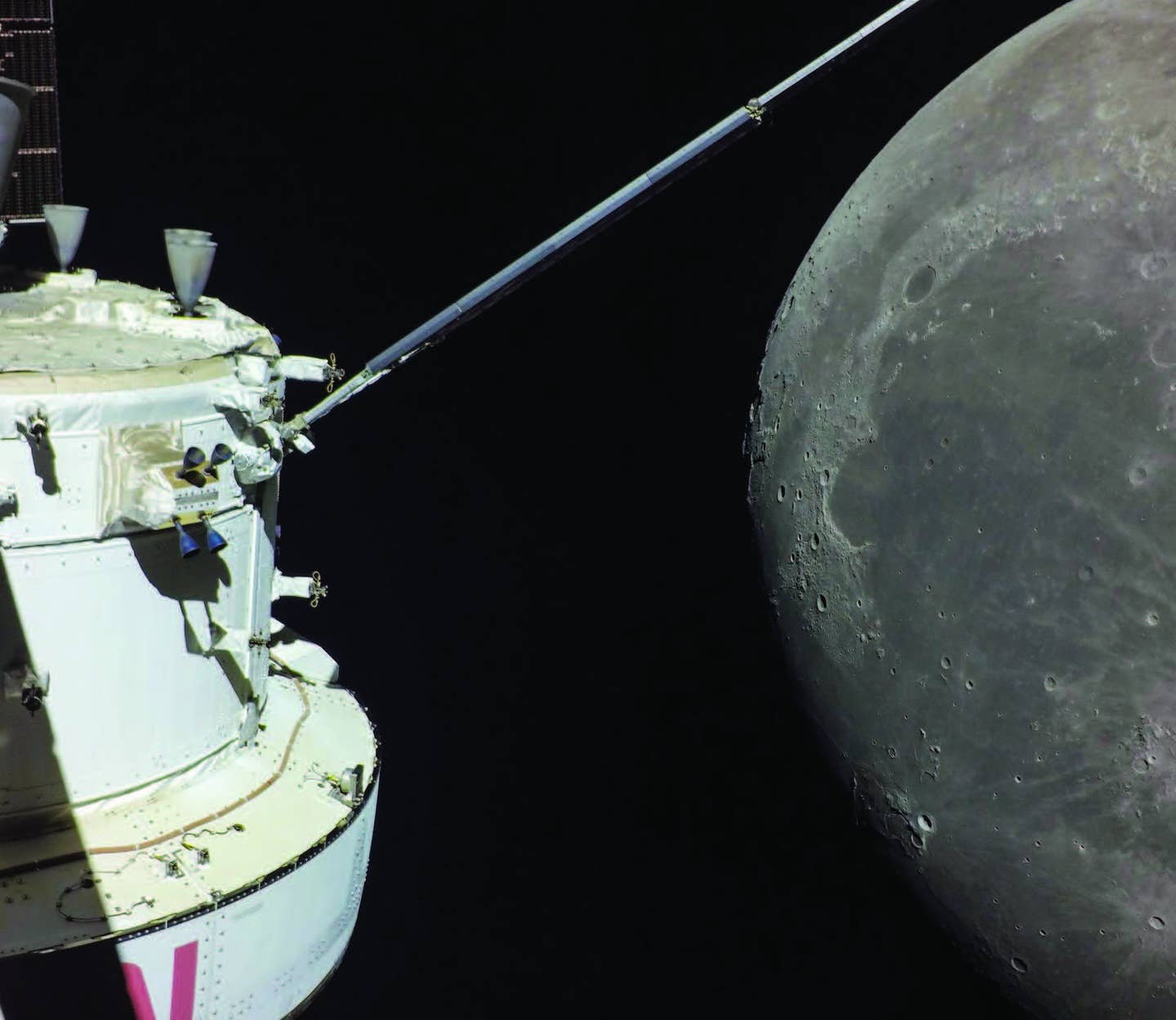

Flying the AS350 with the GFC 600H over the Oregon countryside. [Credit: Stephen Yeates]

As we’re walking out to the 1996 Eurocopter AS350 B2 perched on the pad outside Garmin AT’s offices in Salem, Oregon, I naturally head for the right seat. Because to my fixed-wing pilot brain, that’s where the observer sits, the copilot. And as one with only a handful of hours in rotorcraft in total, that’s what I guess I had expected to do on this demo flight—my introduction to Garmin’s GFC 600H for the AStar.

So when Garmin flight test engineer—and experienced rotorcraft instructor—Jack Loflin gestures me into the right seat, I don’t hesitate. Then I do.

He’s putting me on. Is this wise?

But as it turns out, I’m not only ready for my first AS350 lesson, I am going to have the best assistant I could possibly have. The GFC 600H turned me—for a couple of amazing hours—into a helicopter pilot.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowI’m not saying this is its intended application—or even a good one—but it’s an indication of just how incredible the advances in autoflight have come to the rotorcraft world, that I can even fathom what I’mabout to see and do in the AStar.

Takeoff—And a Cross-Country

The AS350 is also equipped with the Garmin G500 TXi flight display system for rotorcraft, along with the GTN 750 Xi and GTN 650 Xi, allowing for a host of other features—including H-TWAS—to supplementour short cross-country flight. Loflin has planned for us to fly from the Salem Municipal Airport (KSLE) up to the Portland Downtown Heliport (61J)—a gem in that it is one of the few public heliports located in a major metro area in the U.S. We’ll utilize it—it sits on the top of a multistory public parking lot—to pop in for lunch at Loflin’s favorite Lebanese place downtown.

From there, we’ll take off and head back southwest towards the Willamette Valley, dropping in to practice hovering and other spot landings both on-airport and off, on a sandbar in the Willamette River.

From the briefing, I know what to expect of the GFC 600H—now it’s time for Loflin to give me dual on our departure after leading me through the engine start and initial rotation from the pad outside Garmin AT’s flight ops hangar.

Garmin sales manager Pat Coleman has joined us—on our way out to the helicopter, he showed us a few projects inside the Garmin skunkworks in the hangar. Originally certificated in the AS350 in 2019, additions to the GFC 600H’s supplemental type certificate approved model list (STC AML) loom ahead. You can already find the autoflight system in the Bell 505 under a Garmin-owned STC, which came out in mid-2021.

As we lift off and Loflin hands the controls over to me, I feel a sense of low-level anxiety, reflecting on my minimal time in the category. But that quickly melts away as I test out the three axes of flight in small increments as I follow the magenta line that leads us up to Portland proper.

Along our initial flight path, I feel only the barest sense that the autoflight system’s silent hand carries me in the background. It monitors the envelope, speeds, and other parameters to stabilize my relatively level flight. I come down to 500 feet msl to track into the city; we’re indicating about 95 knots.

We are approaching from the south-southeast—the city lies along the Willamette, making for a pleasingly situated downtown, with the heliport we’re aiming for on the western bank. Loflin points out several key obstacles as we approach—at this altitude, nearly everything becomes an obstruction, but the TXi highlights only the most critical at the moment on the multifunction display. The screen shows normal terrain shading with a yellow “obstacle” annunciation as we come up on a series of bridges.

The same obstruction shows on the Garmin GI 275 electronic flight instrument located in the center stack. It has many of the same functions available as those brethren STCed for airplanes—a PFD with attitude, airspeed, altitude, and vertical speed, plus MFD, traffic, terrain, and engine information.

A web of red lines depicts the location of powerlines and other high wires that threaten a helicopter’s path. In order to get the most out of the aircraft’s capabilities, you need to take it into confined areas that would be fatal to fixed wings. It’s a whole different way of looking at the world—and the obstruction data on the MFD goes from towers popping up during an otherwise uneventful flight to an entire maze to navigate down low.

Loflin coaches me so that I take us within about a quarter mile and 100 feet of the landing pad, then takes over to position the AS350 into the relatively confined space. I say “relatively” because there’s plenty of room on the heliport to accommodate at least three helicopters, maybe four, depending on how well they are parked.

He slows us to 35 kias on short approach, bleeding down to hover over the space we’ll leave the AS350 parked in while we grab lunch. It feels surreal—yet just like another one of those “only with GA moments” as the four of us take the elevator down to the street and walk out onto the rather quiet city streets.

Hover Test

We remember the code to get back to the fifth floor of the parking garage—the heliport restricts access to pilots and their guests or customers for clear reasons. It’s time to fire up again and head out to play—and really test the GFC 600H’s mettle against the best amateur rotorcraft pilot moves I can throw at it.

We follow the river out of town, over connecting lakes, and into the valley which is world-renowned for its pinot noir and chardonnay. It’s the very best view of the vines as we pass over them at a neighborly altitude. Often helicopters a reused for frost protection and other agricultural ops over the vineyards—but that is not our mission today.

Our first stop has us joining the traffic pattern at the McMinnville Municipal Airport (KMMV). To me, the airport is famous because it’s home to the Evergreen Aviation Museum—and home to the famous Spruce Goose, the Hughes Hercules eight-engined mammoth that sits barely encased in glass so its enormity can be appreciated even if you never step foot in the museum. We don’t make a stop there today—but both the Gooseand the Boeing 747 in Evergreen livery out front create easy landmarks for me to follow in the pattern.

After the approach, Loflin instructs me through slowing the AS350 down into a hover over a far reach of the taxiway. We have plenty of ramp space here to give me the leeway I need to perform my first AS350 hovering—at first highly assisted by the GFC 600H, in both attitude and yaw hold modes. Then, Loflin turns the magic off. And all of a sudden, the work that the autopilot has been performing behind the scenes becomes dramatically apparent. He takes back the controls periodically to help me along.

We step taxi over to a field northwest of the runway, an open area where we can play a little more. I get to test with and without the GFC 600H and see again just how much it is assisting me as a newb. Now, the benefit to the seasoned pilot lies in the dramatically reduced workload—just like any autopilot—taking the physical work of flying the aircraft from the pilot’s hands so they can focus on something else. And if you think about it, that’s a big change for a helicopter pilot who nearly always has to have both hands engaged with the flight controls during a flight,with only momentary transitions to change radio frequencies or manage checklists.

ESP, Rotor Style

The envelope stability protection that we enjoy in the fixed-wing versions of Garmin’s autoflight systems takes on a new cast in the GFC 600H. H-ESP, as it’s called here, provides both low speed and overspeed protection, as well as limit cueing to help the pilot keep the helicopter upright.

When the pilot maintains f light with the rotor blade plane tilted less than 10 degrees from level, the ESP system sits in the background, monitoring the flight dynamics. When it first senses the rotor plane approaching the beginning of the limit arc either up or down, ESP engages and applies the nudge that’s familiar to those of us accustomed to flying with ESP in other aircraft. If the pilot powers through that nudge and continues to tilt the rotor plane towards the upper limit of the arc, the GFC 600H applies up to a maximum level of force, opposing the pilot’s action and striving to return the rotor plane to a level state.

In the case of a low speed limit approaching, the yellow “LOWSPD” annunciation appears on the pilot’s primary flight display. Similarly, if a maximum speed limit is anticipated, the yellow “MAXSPD” highlights. A LVL mode returns the helicopter to a zero fpm vertical and zero bank angle lateral attitude when actuated.

Flying the Approach

Coming back into Salem, we opt for another one of the system’s enormous safety benefits—the ability to fly a coupled approach. The AS350 we’re in is placarded “VFR Only,” and many helicopter pilots do not possess an instrument rating. It’s not that they wouldn’t ever need the skill, but it comes up less often than it does for airplane pilots.

That is, until it takes on critical importance. Recalling the accident that took Kobe Bryant’s life and those of his family and friends in January 2020, it’s sobering to contemplate what would have been different if the pilot had been able to maintain situational awareness.

The GFC 600H, when integrated with the NXi, allows even a non-rated pilot to engage an approach as a safety tool in lowering visibility. We had set up the RNAV (GPS) approach to Runway 31 at KSLE and I engaged the AP through a similar mode controller as other Garmin autoflight systems in the series. Though I cannot tell you how many times I’ve watched the approach proceedings unfold on an MFD over the course of my career, it’s wild to see it happen in a helicopter. Our speed on the approach isn’t too slow—though it’s slower than what most of us are accustomed to—but the outcome is the same. We’ve returned to a safe position from which to hover-taxi to our final landing point on the airport.

That’s when it really hits me—the GFC 600H makes the helicopter as easy to keep in level flight or a stabilized approach as an airplane. I mean, Coleman had said it in our initial conversations, but it turns out not to be just a marketing line. The autopilot shadowing me allowed me to manipulate the controls in a way more akin to my ingrained skill controlling an airplane. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed my rotorcraft lessons before, but flying a helicopter without this felt like pirouetting on the head of a pin—a delicate balancing act full of nuance and retraining my muscle memory.

While this isn’t a panacea—what happens to the pilot who flies with it on all the time when it breaks, and they suddenly have to hand-fly? But that’s a question we ask in the fixed-wing world too—and we make sure to train both VFR and IFR flight without the automation as a result, to keep those skills sharp.

The other piece is that it made the rotorcraft rating feel approachable—and one less barrier to entry, perhaps. But most of all, the real capability of the GFC 600H changes the game for safety.

This article was originally published in the March 2023 Issue 935 of FLYING

Genesys Autoflight for Helicopters

Genesys helicopter’s speed range, with altitude-command and altitude-hold functions. Fly-through system engagement is available in all flight regimes, from startup to shutdown, and the system features rugged, redundant flight control computers. Total weight installed is less than 35 pounds, and it operates in a fail-operable manner. The GRC 3000 is currently certificated on the Airbus EC-145e and the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk.

Aerosystems (formerly S-TEC) entered the autoflight arena in 2014 with its HeliSAS two-axis VFR autopilot and stability augmentation system for light rotorcraft on the AS350 as well as the EC 130, followed by the Bell 206B/L and 407, and the Robinson R44 and R66. A three-axis option is available for the Bell 505. The company has delivered more than 1,000 units to date.

The HeliSAS incorporates the ability to track heading and nav functions (VOR, LOC, GPS), with course intercept capability, and manage forward speed, vertical speed, and altitude.

With units weighing less than 15 pounds, the HeliSAS also features an auto-recovery mode to return the helicopter to a neutral attitude when the pilot loses situational awareness. And according to the company, its system has also allowed pilots with no prior rotorcraft experience to maintain the helicopter in a hover “with very little practice.”

Genesys also makes an IFR autoflight system, the GRC 3000. The two- or three-axis autopilot includes auto-recovery to near-level flight attitude throughout the

This sidebar was originally published in the March 2023 Issue 935 of FLYING.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox