Bam! In Life and in the Air, Things Can Change in a Hurry

A cancer diagnosis shows this longtime pilot just how quickly one’s entire perspective can be altered.

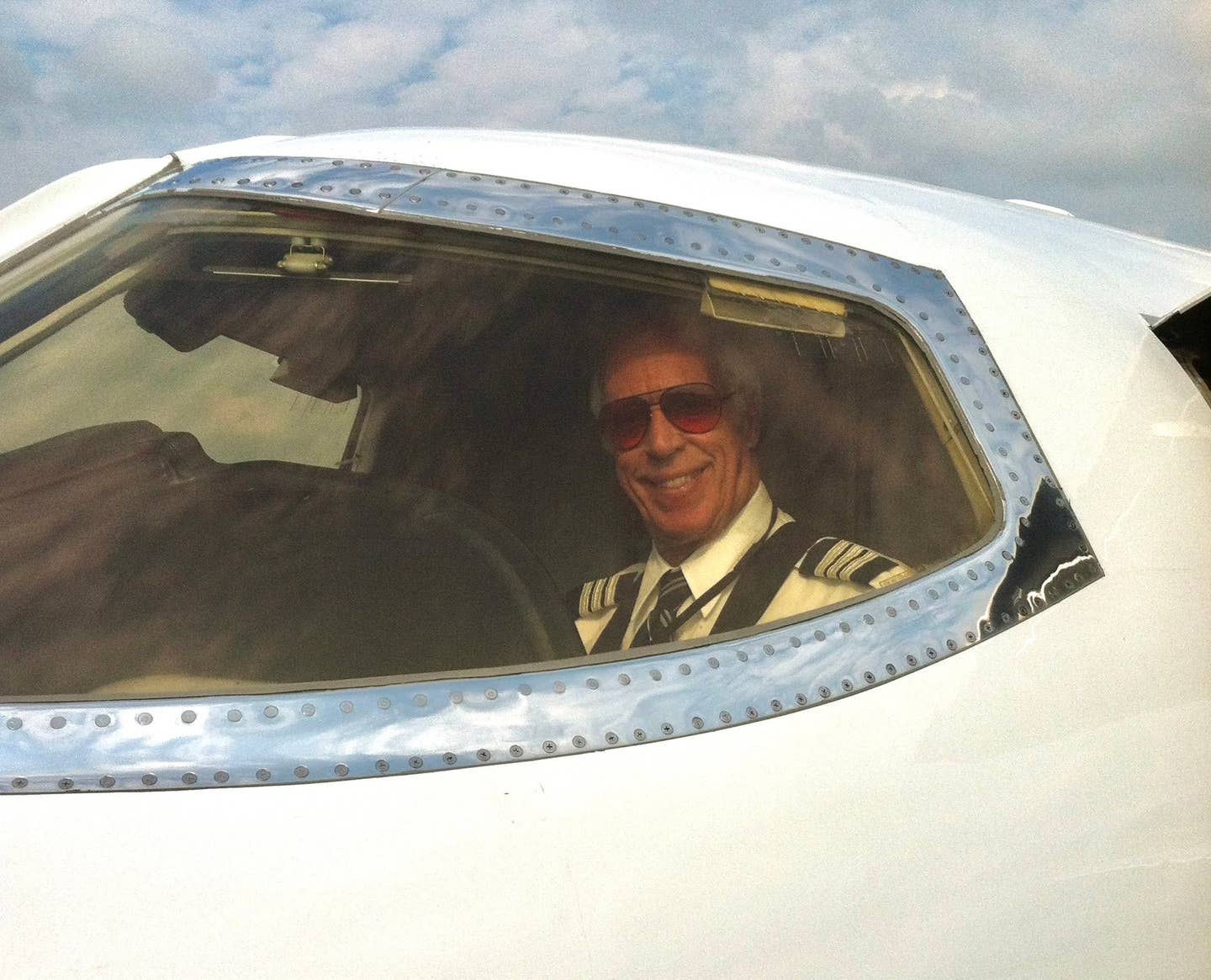

FLYING contributor Dick Karl says that dealing with an unforeseen health crisis is a reminder that your week, his week, anybody’s week can go from anticipating flight to hanging on for dear life. [iStock]

In life and in the air, things can change in a hurry.

Cruising westbound at FL 430 with just more than an hour to the destination, we’re chatting about our groundspeed, which is just tickling 400 knots, the headwinds, and, despite constant rearrangement of the sun visors, the annoying persistence of sun in both our faces.

Suddenly, BAM!

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowStunned, I can’t make out what has happened, but whatever it is, it is catastrophic. The master warning is blaring, and I think I see some flashing lights, but the air is filled with condensation and junk. Sudden catastrophic decompression.

We wordlessly execute our memory items. Don oxygen mask, switch to mic oxy mask. With communication established, we go to the emergency descent memory items. Throttles to idle, speed brakes deployed, start with 15-degree nose down. If nothing seems to be falling off the airplane, accelerate to MMO. Check pax oxygen. Go to the checklist.

This was not a dream, nor was it real, yet it was pretty much the equivalent of what happened over the summer. It wasn’t the airplane that had a problem—it was me.

After a leisurely hike with my wife, Cathy, son, and his family in the Ledges of New Hampshire, we went back to the cottage, sent the parents home to Boston, and had dinner. We had bought some chicken at a farm near us in Vermont. The chicken had led a coddled life; no hormones, nothing but the best feed, and plenty of room to roam. Cathy made a sheet pan chicken dinner.

I was really looking forward to the next week. The grandkids were great, and my flying friend, Bill Alpert, had invited me to copilot a Cessna Citation CJ2+ from Nantucket, Massachusetts, to Tampa, Florida, at the end of the week. Our Beechcraft P-Baron should’ve been out of its Florida annual by then, so I could fly it back to New Hampshire. What a package.

About an hour later, BAM!

Violent vomiting and other even less appealing gastrointestinal events alternated in bewildering fashion. We’ve all had the GIs at some point, but this was different. Cathy kept busy changing sheets and cleaning me up. The kids slept, obliviously.

By morning I had passed out twice, once on the bathroom floor, once next to the bed. The place was a mess. By late afternoon, I had not improved, had lost 5 to 7 liters of fluid, and Cathy called the fire department. The responders had a chair for just this kind of situation and took me down a flight of stairs as I waxed in and out of consciousness. “Keep your hands in,” I heard them say. In the ambulance they started an IV. Off we went to Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, arriving just at shift change: 7 p.m.. Just another day at the office for my saviors.

An initial assessment found I was perilously low on red blood cells that carry oxygen and white blood cells that fight infection. The diagnosis of B12 deficiency was entertained, I’m told, but I missed most of the discussion. I was out of it. By the time I was capable of understanding, more sinister diagnoses were being discussed by various consulting physicians. Resuscitated, I was fit to go home on day 5.

Over the next month, the diagnosis became clear: acute myeloid leukemia. The worst. Five-year survival rate for people over 20 is 28 percent. Not only that, but those survival statistics are for patients younger than me. And then this: The only known cure for my subtype is a bone marrow transplant. Don’t Google this. A month in the hospital is the least of it, and the therapy itself carries a 25 percent mortality rate, I’m told.

What the heck does this have to do with flying airplanes?

One, it is a reminder how your week, my week, anybody’s week can go from anticipating flight to hanging on for dear life. As a young surgeon, I learned this in the emergency rooms where I met that motorcycle jockey who left home one morning with high hopes and the feel of speed that made his T-shirt climb up his back but was now lying motionless in a bed with a bad spinal injury. Motorcycles are often referred to as “donor cycles” in hospitals.

Two, just as you are completely dependent on the expertise of the folks up front on the flight deck when you board an airliner, you are putting your life in the hands of people you just met. You better hope that the airline has rigorous selection policies, expert training, and superb maintenance, not to mention strict criteria for the mental health of the folks in the jumpseat. Same goes for these new doctors. They seem pretty young and sure of themselves. Oh, wait, that was once me.

Three, with luck, you are on a professional river from ground school to mastery to captain’s wings on a Boeing 787. These accomplishments, while impressive, are of little help in a situation like this. Like your progress in the profession, largely determined by hire date and seniority, you become a leaf on a river. It is flowing, and you have little ability to steer a course. Your doctors, your diagnosis, and the system of American healthcare now have you in its maw.

Four, you have friends and family who care about you way more than you had dared to hope. My group of male friends—doctors, lawyers, newspaper journalists, pilots, IT gurus, former NFL players, and mechanics—have stepped up with a platter of helpful and encouraging selections. Who knew that Graeter’s Ice Cream from Cincinnati is the best? I’ve got 10 1-pint containers straining the freezer door.

I’m confident that there will be more aviation themes to this “journey.” I’ll try to avoid the maudlin and tell you what it’s like. Such intel may come in handy someday.

Meanwhile, the Baron is up for sale.

This column first appeared in the January-February 2024/Issue 945 of FLYING’s print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox