Beechcraft Twin Quad: A ‘Feederliner’ That Almost Was

Though the V-tail was the most notable design feature of the aircraft, it paled in comparison to the originality and uniqueness of the engine layout.

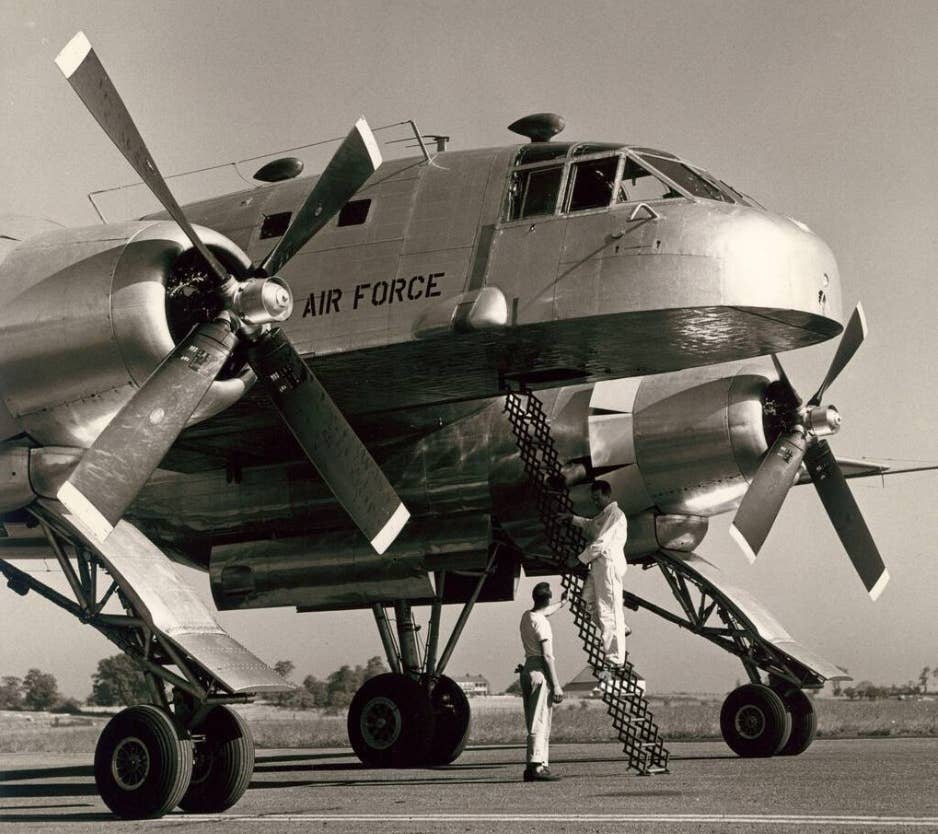

Sporting Beechcraft’s distinctive V-tail configuration, the truly unique design characteristics of the Twin Quad were hidden beneath the surface. [Credit: Beechcraft]

In the years following World War II, the economy was booming, Americans were beginning to travel, and aircraft manufacturers were brimming with experienced teams of engineers. With the demand for military aircraft subsiding, virtually all of these companies began exploring new avenues for product development and innovation. It didn’t take Beechcraft long to identify civil aviation as a burgeoning opportunity.

Fresh off the success of the V-tail Bonanza and the larger, 8-to-10 passenger Model 18, Beechcraft management explored the market and noticed a gap in the industry’s product offerings. Prior to the war, types such as the Ford Trimotor, Boeing 247, and Curtiss taildraggers served as the era’s smaller “regional airliners,” but the war effort paused any further development of that segment. Referring to it as a “Feederliner,” Beechcraft reasoned that a small, modernized civil airliner was just what the industry needed.

Dedicating significant engineering and marketing resources to the project, the team got to work. It aimed to position the aircraft as a solution for passenger as well as cargo transport. It opted for a high-wing configuration, an easily convertible cabin layout, and a cargo door in the forward left fuselage, naming the final product the “Twin Quad.”

With a wingspan of 70 feet, a length of 51 feet, and a height of 19 feet, 4 inches, the Beechcraft 34 Twin Quad was a sizable machine. Ironically, each dimension is nearly identical—within 1 to 4 feet—to the Cessna SkyCourier, the latest offering from Beechcraft’s successor. Even the maximum takeoff weight of 19,500 pounds is within 500 pounds of the modern twin turboprop.

The team decided to incorporate a V-tail into the design, first installing it on an existing AT-10 Wichita twin for testing purposes. This enabled them to evaluate the tail’s effectiveness at providing directional control on a multi-engine aircraft of similar size and weight to the Twin Quad before finalizing and freezing the design.

It’s possible the V-tail was pursued primarily because of the technical advantages it was thought to provide. It’s also possible it offered more value to the marketing department as an instantly identifiable branding feature that visually differentiated it from the competition. Whatever the driving reason, Beechcraft ultimately incorporated the V-tail into the final design.

Though the V-tail was the most notable design feature of the aircraft from a visual standpoint, it paled in comparison to the originality and uniqueness of the engine layout.

In an effort to harness the maximum power in the smallest, most aerodynamic packaging possible, the team opted to utilize four 375 hp Lycoming GSO-580 flat-8 piston engines and buried them entirely within the wing. The engines were configured in pairs, with each coupled together and driving a single propeller via clutches and a gearbox. The clutches were designed so that engine torque compressed and engaged the clutch discs.

In the event of an engine failure, the failed engine would automatically disengage from the gearbox, and the remaining engine would continue to drive the propeller. This feature was presented as a safety improvement—although the loss of one engine would result in a power reduction, it would present no corresponding asymmetric control issues.

The Twin Quad used two massive full-feathering, two-blade propellers for propulsion, and naturally, they were driven through reduction gearing. At 11 feet long, if the engines were to turn them directly at a normal cruise rpm, the propeller tip speeds would have exceeded Mach 1.5. The reduction gearing provided a ratio of 40:21, or roughly 2:1, bringing the propeller rpm range down to a quiet and comfortable 1,500 rpm in cruise flight.

During engine shutdown, the engine clutches would disengage entirely. A note in the operating manual advises that if high-velocity wind rotates the propellers after shutdown, the clutches may be reengaged to lock them into position. Presumably, standard operations would call for the clutches to be engaged regardless, as the sight of rotating propellers on a vacant, parked aircraft would naturally create concern for any observers on the ramp.

Because the Twin Quad was designed for airline operations, it was equipped with full anti-icing capability. Two combustion heaters—one for the wing, and one for the tail—provided heat for the leading edges that was distributed along the insides of the leading-edge skins. The propellers were electrically deiced, and the cabin heater ducted hot air into the space between the two panes of glass that made up each cockpit windscreen.

The Twin Quad made its first flight in autumn 1947. Shortly thereafter, the marketing team stopped using the term “Feederliner” to describe the aircraft, instead switching to “Beechcraft Transport.” This indicated a change in marketing strategy to emphasize non-airline operations, which likely included executive transport.

Detailed cruise performance wasn’t provided in the preliminary flight manual, but VNE is listed as 270 mph and VNO as 220 mph. Minimum takeoff climb speed is listed as 96 mph, and the bottom of the white arc is 75 mph.

Given the total horsepower available, the Twin Quad’s engine-out takeoff performance seems fairly decent. In the event of an engine failure after V1 at the maximum weight of 19,500 pounds, the charts indicate it will clear a 50-foot obstacle in just below 3,500 feet at sea level. By comparison, the modern Cessna SkyCourier requires 2,740 feet at roughly the same weight with both engines operating and twice as much power available. Landing distance over a 50-foot obstacle is listed as 2,000 feet at sea level and maximum weight.

The charts optimistically include separate listings showing performance with 40-mph headwinds. It is unclear whether this is a function of an overly optimistic marketing team or simply reflected the reality of everyday weather conditions in Wichita, Kansas.

Range figures aren’t provided, but endurance can be calculated with the available data. Given the Twin Quad’s total fuel capacity of 536 gallons and the fuel consumption figures of 130 total gallons per hour at maximum continuous power and 80 total gallons per hour at 75 percent power, the resulting endurance would have been 4.1 to 6.7 hours.

Tragedy struck during a certification test flight in Wichita on January 7, 1949. Just after liftoff, an electrical fire occurred. While attempting to extinguish it, a crew member reportedly turned off an “emergency master switch” that resulted in both engines shutting down. The aircraft then stalled and went down, killing one of the pilots.

Following the incident, Beechcraft terminated the program entirely. No specific reason was provided, but it’s possible the decision was driven in part because of a lukewarm response from the market. Ultimately and unfortunately, what remained of the Twin Quad was scrapped.

Today, all that remains is a small handful of photos and scraps of documentation. And while the large Bristol Brabazon airliner flew with a nearly identical engine/propeller arrangement later that year, it would ultimately succumb to the same fate—canceled, scrapped, and relegated to the dusty shelves of aviation history.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox