Training the Trainers Remains Critical

Learn how to teach flying by learning how to learn.

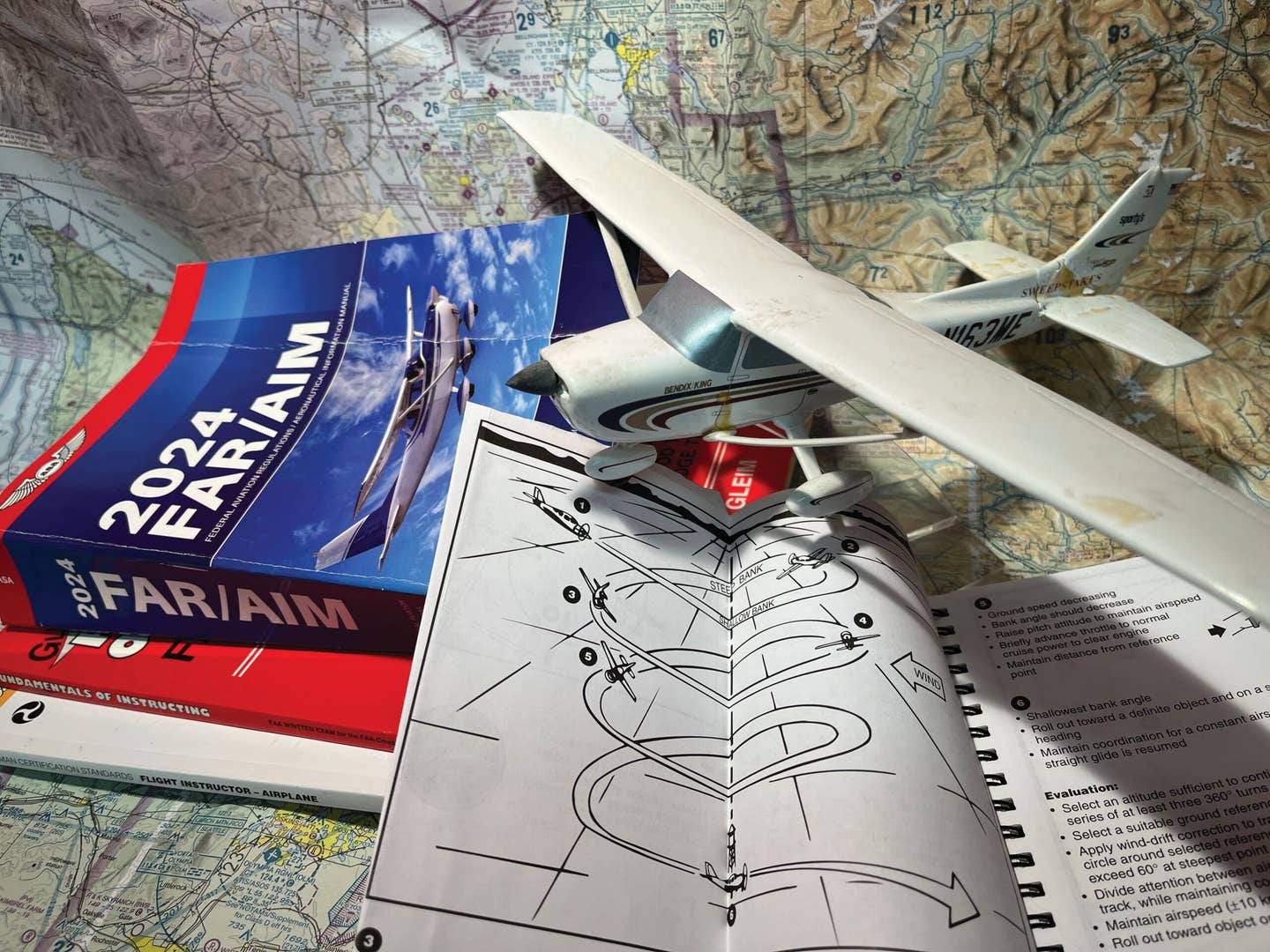

It can be very frustrating when the instructor’s teaching style doesn’t mesh with the learner’s learning style. [Meg Godlewski]

By the time you get to high school, most people have a pretty good idea of how they learn best. Maybe it is watching a video or a hands-on demonstration. For others, it is reading a detailed description of a process. Some learners do best “gronking” (Seattle-tech speak for figuring something out without instructions) their way through a process without help, while others prefer step-by-step verbal instructions and immediate feedback.

It can be very frustrating when the instructor’s teaching style doesn’t mesh with the learner’s learning style. And here’s the kicker. When you are beginning your instructor career, you won’t know your teaching style until you practice teaching under the guidance of a more experienced CFI.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowFundamentals of Instruction

The Aviation Instructor’s Handbook, the FAA’s text for CFIs (FAA-H-8083-9B), is a good place to begin the transition from learner to teacher, as it walks the applicant through the Fundamentals of Instruction, also known as the FOI.

You will learn about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—beginning with the learner’s physical needs, such as being warm enough or cool enough, rested, fed, free from threat, etc., that must be met before learning can take place.

The book can be downloaded from the FAA’s website and kept on a tablet, or it can be printed out and put in a binder, or you can buy the bound book from a retailer. The latter is popular with instructor candidates who know from previous life experience that they need to hold something in their hands and physically turn pages for learning to take place.

Application of a Syllabus and Lesson Plans

All flight training should begin on the ground, yet so many instructor candidates are surprised when asked to use a syllabus and create lesson plans to cover the knowledge and tasks that must be learned. The CFI is expected to brief those lessons before heading out to the aircraft.

The reason the syllabus and lesson plans can come as a surprise is because a great many instructors use “the folklore method” of instruction, teaching as they were taught, usually by demonstration without much explanation. Often the learner has no idea where this information is coming from.

- READ MORE: A Look at the Evolution of Flight Training

For this reason the CFI should use a syllabus and make sure the learner has a copy of it and brings it with them to each lesson. A syllabus helps the learner keep engaged in their training as they can see their progress, but this doesn’t mean the CFI should use the check-the-box style of instruction. The whole purpose of a syllabus and lessons is to learn something.

Doing a flight just to check that box—OK, we did a night flight—is a waste of the learner’s time. This is particularly noticeable on cross-country flights if the learner is unprepared and therefore little more than self-loading ballast as the CFI does most of the flying and navigating.

The learner must be taught how to use the syllabus just as they are taught how to use a checklist or the FAR/AIM. This makes sure they follow the solo requirements of the certificate. When a learner heads out to the practice area for their post-solo flights, they need to be practicing previously learned maneuvers, yet so many learners go rogue. Some attempt to fly over a friend’s house or head off to another airport without the required instructor approval or proper training required for that airspace.

Lesson Plans

Lesson plans can be purchased commercially, but many instructor applicants find they learn better and therefore teach better if they create their own. The beauty of the digital age is that you can adjust the lesson plans with a few keystrokes, and add as well as subtract things.

To know what information is required in a lesson plan try using this mnemonic device:

Only Elephants Enjoy Ingesting Lemon Candy Corn, Really.

It stands for Objective of the lesson (for example, learn how to preflight the aircraft); Elements of the lesson (the importance of taking your time and using a checklist); Equipment used (such as a checklist, the pipette, an oil rag and window cleaner); Instructor’s actions (demonstrating something), Learner’s actions, Completion standards (they will learn how to do the task); Common errors (for example, forgetting to use a checklist); and finally, References (as in where you culled your information from, like the Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge or the POH the aircraft). I find this last one to be very important because it impresses on the learner that the CFI backs up their knowledge with a published and reputable source and isn’t relying on tribal knowledge.

Lesson plans are best used on the ground during the pre-brief. A common misconception is that they are a script to be read. This is not something you’d have in the airplane, as by the time you are ready for your check ride, you should be able to deliver the lesson. The plan is more of an outline, and you should be able to fill in the gaps.

Knowledge and Experience Required

Refer to the appropriate Airman Certificate Standards for the certificate you are teaching and create a lesson plan for the required maneuvers, tasks, and knowledge, and cross-reference this with the appropriate section of the Federal Aviation Regulations/Aeronautical Information Manual to make sure you have everything covered, both in the air and on the ground.

The length of lessons vary. For a private pilot candidate in the first 15 hours or so, the total time the CFI spends with the learner in the air is usually around 1.0 to 1.3 hours. The minute the learner starts to show signs of fatigue it’s time to land. Expect at least 0.2 on the ground for the preflight briefing and the postflight briefing.

- READ MORE: How to Beat the Summer Heat When Flying

Have the syllabus with you in the cockpit. The best CFIs often make notes on both their or the learner’s syllabus to remind them what they worked on, what needs improvement, and what needs to be done to achieve completion standards.

Keep in mind the lesson plans need not be perfect at first. It is OK to stumble and make changes because that means learning is taking place.

Expedite Learning to Teach

If your FBO has a face-to-face ground school, ask to sit in on a few classes. Observation is an excellent way to learn. You may even ask if perhaps you could teach a lesson, for example, weight and balance, or airport traffic pattern.

Sadly, there are instructor candidates who balk at this idea, fearing they will get in trouble with the FAA because they do not hold an instructor certificate, although the CFI in charge of the class is present during the student teaching and still responsible for the material presented.

Student teaching is an opportunity for you to get experience and will help make you a better instructor.

Remember, there is a big difference between being able to teach in the air—where the learner imitates what has been shown to them—and teaching on the ground. Strive to master both.

This column first appeared in the November Issue 952 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox