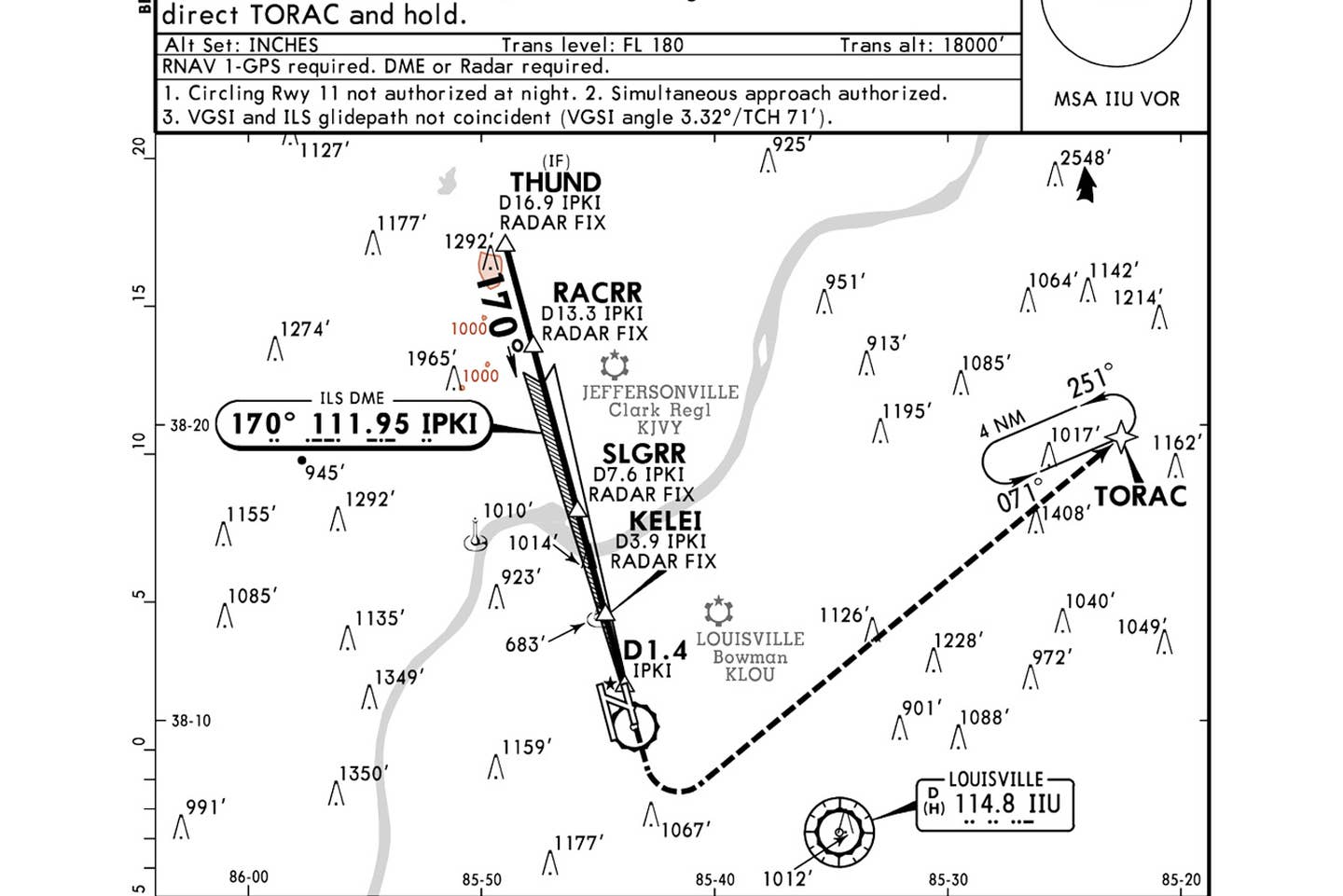

Louisville ILS or LOC Runway 17L Courtesy Jeppesen

If you enjoy watching airplanes, especially any of the quickly declining global fleet of jumbo jets, Muhammad Ali International—the old Standiford Field (KSDF)—in Louisville, Kentucky, is an excellent place. The home of UPS, KSDF offers the opportunity to see large Boeings—747s, 757s and 767s—as well as Airbus A300s and McDonnell Douglas MD-11s operating day and night. With slightly more than 175,000 takeoffs and landings annually, most of them air carrier, a light-aircraft pilot operating through KSDF needs to be alert on the ground and in the air for these wake-turbulence producers.

Parallel Approaches

Note 2 offers pilots a serious piece of information as they approach Runway 17 Left: An airliner might be shooting an approach to the parallel 17 Right—referred to as “simultaneous approaches”—bringing with it the need to be alert to the wind and the location of the heavy aircraft to avoid wake turbulence. The note also reminds pilots to be certain they’re looking at the correct runway when they do break out on the approach to 17 Left. With a strong west wind, the aircraft’s nose would crab into the wind and possibly aim at 17 Right. Pilots should also not be surprised to see another airplane off their right as close as 3,000 feet away, lined up for the right side.

GPS Required

Even if the pilot plans to use only the ILS components of this procedure, an “RNAV 1-GPS” is required to reach the TORAC waypoint in the missed approach, should it be needed.

How Low Can You Go?

Approach minimums are important to review so pilots will understand the distance between them and the ground if they don’t break out until at minimums. Common ILS minimums are 200 feet agl and half a mile. That means that even though your altimeter reads 699 feet at the decision altitude, the airplane will be just 200 feet above the ground. Understanding this will help correlate the reported ceilings on an ATIS, AWOS or ASOS with what pilots will experience. If the reported ceiling is 400 overcast, the pilot can expect to break out of the clouds and see the runway as the altimeter unwinds through 899 feet (TDZE 499 feet plus the 400-foot ceiling), though pilots should always be prepared that the ceiling might be worse than reported. If the glideslope were inoperative, the pilot is working with localizer-only minimums. Using that same 400-foot overcast, pilots could descend only to 1,000 feet msl, or about 501 feet agl. A different approach may be in order altogether. In any event, as pointed out by Note 3 near the top of the plate, pilots should be prepared that, even though they may be established on the glideslope, the visual approach indicator probably won’t show the same on-glidepath indication.

Check out more charts: Chart Wise

DME Won’t Read Zero at the Loc-Only MAP

This localizer-only approach’s MDA is 1,000 feet. With no runway in sight at minimums, the only option is a missed approach. But note that, even though the co-located VHF/ILS DME is counting down to zero as the aircraft approaches the runway, it won’t indicate zero at the missed approach point—but 1.4 miles. The GPS would read zero at the MAP.

Simple Missed Approach

The missed approach for 17 Left seems simple at first, but it could catch a pilot who had not briefed the procedure. Before beginning the left turn and heading for the TORAC waypoint and the 4 nm GPS hold, the pilot must climb straight ahead to 1,600 feet, most likely to remain clear of the obstacles.

This story appeared in the January-February 2021 issue of Flying Magazine

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox