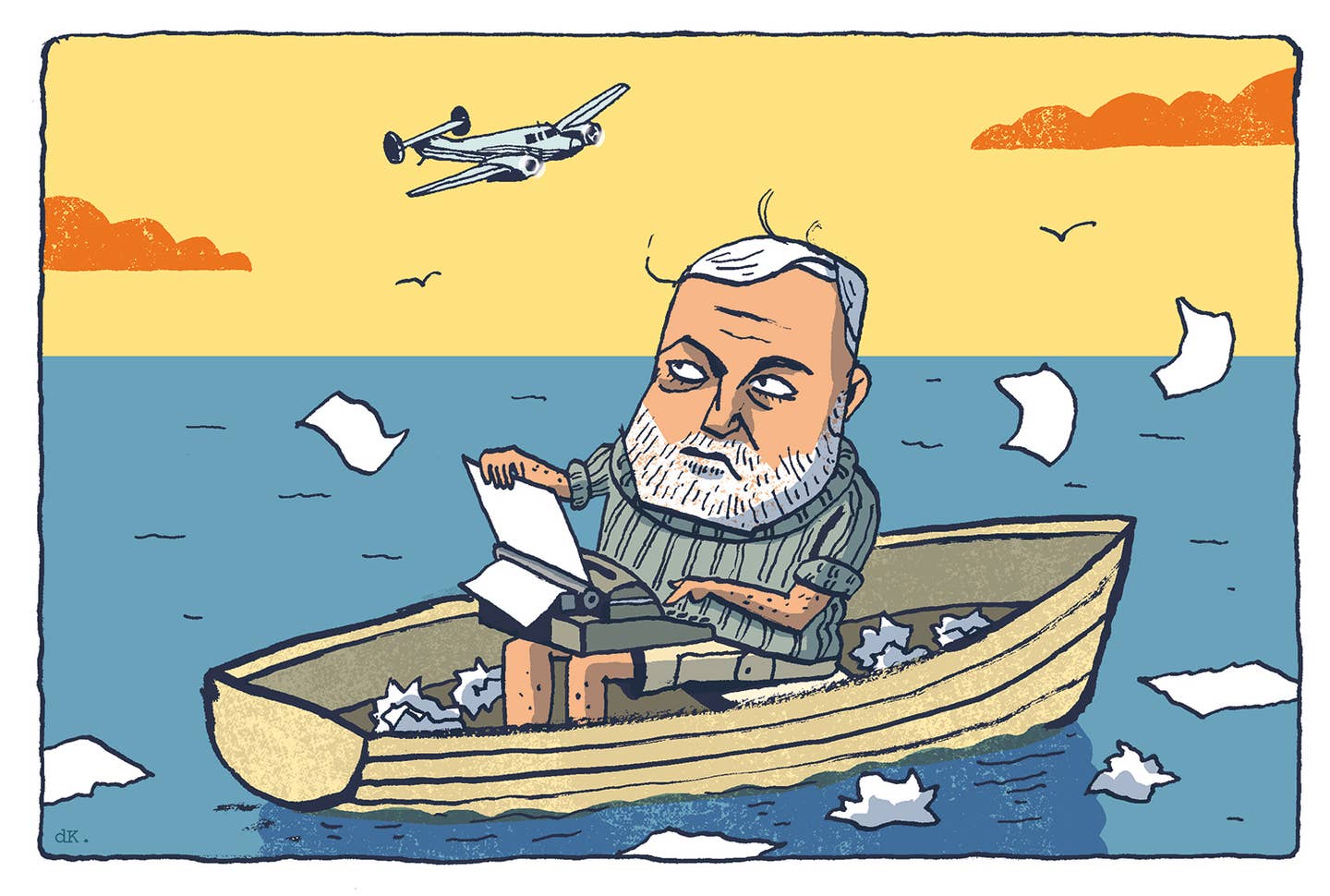

Ernest Hemingway always regretted never having written about aviation. Philippe de Kemmeter

Well, the cops say, “nobody knows what goes on in a squad car.” And all married people know that no one outside ever knows what goes on in a marriage. My particular racket is show business, and I can report, from 40 years’ experience, that nobody who wasn’t there knows what happened on a movie set.

The set is particular in this way too: One must be a working part of the operation to understand the things one hears and sees. One cannot “visit” the film set, the squad car or the marriage. Interactions in these hermetic environments are, to the passers-by, incomprehensible, where they are even perceived. For the byplay in these close, mutually dedicated and profoundly busy associations, in addition to being rapid and technical, is intimate.

Folks called “producers” stand around on a film set, the same expression on their face as that found on the odd man out at a conversation in a foreign language with which he is unfamiliar. This fellow is usually trying to strike a balance between a demeanor falsely claiming some understanding and a frank and sad proclamation of his ignorance.

Now, Ernest Hemingway said that he always regretted he had never written about aviation. Here was a fellow dead good at descriptions of some highly technical endeavors; I note boating, fishing and hunting. Why did he (correctly) feel himself balked of the outlet of aviation writing?

Because, to do so — he understood — requires two specific skills: One needs to be able to write, and one needs to know how to fly.

Almost all aviation writing is purple prose. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Anne Morrow Lindbergh and Beryl Markham all wrote about the supposed drama of the landscape and the clouds and so on. They could fly, and, in flying, they sought to express their love in prose. The problem, however, is that the drama of flight does not take place between the pilot and the environment, but between the airplane and the pilot, and between the pilot and himself.

The best aviation writing takes place not in novels, or films, but in the flying magazines. Here, pilots are communicating, in technical language, the drama that took place, finally, within themselves: difficulties, happenstance or error compounded by laziness, fatigue, ignorance or pride; ignorance beaten out through near-averted tragedy; theory triumphing over fear, or excised through practice.

The best book written about aviation is Fate Is the Hunter by the great Ernest Gann. Its contemporary descendants can be found in I Learned About Flying from That, Never Again and the magazine writing of pilots for pilots.

Cops, firefighters, armed-forces members, medical personnel and married couples communicate in a technical, mutually evolved hyper-quick language of abbreviations, pauses, interactions, gestures and omissions. Not only the information but the nature of the language itself is generally hidden from the uninitiated. It is not only technical, but allusive, which is to say that in its appeal to commonality and its strict cadences and delimited vocabulary, it shares most of the attributes of poetry.

The other day, I flew from Santa Monica, California, to Salt Lake and back the next morning. That, in the Bonanza, was eight hours out of 24, listening and talking to ATC.

It occurred to me that it was a quite intimate experience. I, as the PIC, was, as always, grateful for the professionalism, courtesy, patience and humor of the men and women handling the busy airspace. The flight was (for the Bonanza and me) long, straight, generally over the desert, and most of the communications were not for me. But I got to listen.

There was the drama one could detect, in the competence of the commercial and military pilots, the result of endless hours; in the private pilots, the relaxed and often folksy diction and vocabulary of the old-timer, the confusion and, sometimes, the apprehension or fear of the new.

And, through it all, there was the voice on the ground, guiding, clarifying, correcting and caring for the folks who were trusting our lives to them.

The intimacy of the thing was staggering. Here, a minutely overlong pause could indicate amusement, consternation, disbelief; an infinitesimal change in inflection would — to those who understood the language — communicate disapproval, apprehension or warning (the controllers are there to aid, but are not, strictly, allowed to offer suggestions).

The controllers are, generally, so patient not only with the unprepared, mistaken or foolish, but with those who, independently, or additionally, don’t speak English very well. (Southern California has a large population of Hispanic and Asian pilots; and, to my ear, the even less-comprehensible assassins of the English language, the English.)

There is actual life-and-death drama in the sky, and it’s all expressed in the vocabulary of perhaps 200 words, and interchanges of five seconds. The controllers may be testy, and curt — I only heard one angry once. They, being overworked and concerned, are astoundingly rarely wrong, and their camaraderie and understanding is one of the delights the nature of which eluded Hemingway, but whose existence he intuited: “Have a nice day,” “Fly safe,” “See ya,” “Thank you for your help” and, my two favorites: “Welcome home” and “This is New York Center.”

Frank Wead, an ex-military pilot, wrote an unfortunate number of flying films in the 1930s. In each, the stunt-flying sequences are punctuated by the deadening “plot,” which is always either two guys and a girl, or one pilot feuding with his superior. Wead was trying to express his love of flying in a way his audience might understand. He didn’t make it.

There is some marvelous aviation writing in the novels of Nevil Shute, a pilot and aeronautical designer. And in the stories of Frederick Forsyth, who flew for the Royal Air Force. Here, as in aviation magazines, is the drama that eluded Hemingway and the underlying secret: The drama in aviation writing does not rest in writing about flight, but in writing about a flight.

For each flight, for the pilot, is structured like a drama. It has an objective (called a destination), a plan, containing a beginning, a middle and an end, after which the pilot is free to compare his objective to his performance, re-evaluate his plan and draw conclusions based upon his lack of perfection.

The task of the pilot, curiously, mirrors the task of the hero in this: His job is to eliminate drama. The dramatic hero exists not to create drama, but to restore order to a disrupted situation. He faces human opposition, chance, fate and his own flawed understanding. The pilot confronts weather, malfunction, chance and his own limitations, errors and emotions.

Aviation drama can’t be found in Wings of the Navy, Courrier Sud or West with the Night; it takes place within the pilot, and between the pilot and his colleagues on the ground. I’d say it might make a good radio play, but it already is a good radio play. One just has to be able to speak the language.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox