The Special Olympics Airlift is the largest peacetime airlift in the world with an aircraft landing every two minutes. [Courtesy: Dick Karl]

A bowling ball can weigh up to 16 pounds. A Bocce ball weighs 2 pounds. Bocce balls come in eight packs, so 16 pounds. Why would you want to know this?

When I signed up at a Citation Jet Pilots (CJP) meeting to provide support for the Special Olympics Airlift in the Cessna CJ1 that my wife, Cathy, and I own, I had no idea that I’d be looking up bowling ball weights.

The Special Olympics USA Games are held every four years. Athletes with intellectual disabilities train and compete year round for a chance to represent their state at the games. I signed up partly because retired NFL quarterback Peyton Manning was the honorary chairman. I never saw Peyton, though.

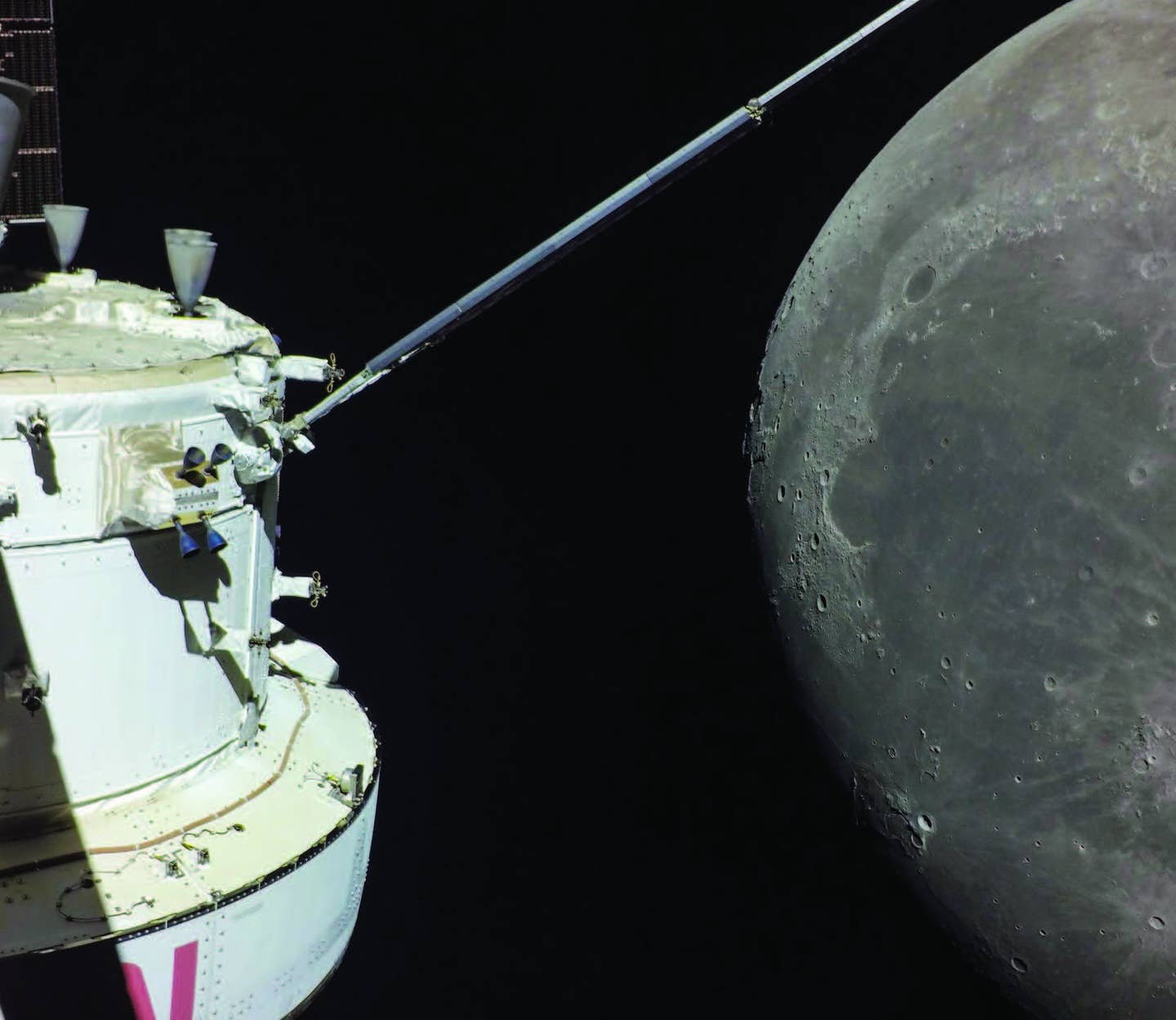

What I did see was awesome, amazing, and uplifting. Textron Aviation coordinated the airlift, bringing these athletes in more than 120 private jets and turboprops to Orlando, Florida. Each airplane was given a “Dove” call sign to give them priority treatment by ATC. We were assigned to pick up four athletes in New Orleans, Louisiana, at Lakefront Airport (KNEW) and bring them to Orlando Executive Airport (KORL).

Days before the flight, during a careful briefing by Wendy Koziol of Dove Relations, Textron SOA (Special Olympics Airlift), we were assigned two bowlers, a Bocce player, and a coach. No single-pilot operations were allowed (to my knowledge), and my insurance company had to provide Textron with verification of insurance. We were given an assigned takeoff time of 0655. Textron estimated our flight time to be one hour and 38 minutes. ForeFlight said one hour, 33 minutes. In the end, the trip took almost two hours.

We were assigned the call sign “Dove 47” and an overland route to Orlando: CEW, CABLO, BIGDE, SHREK2 Arrival. I noted that all the “Doves” ended up on the SHREK2, too. We were told that there would be an aircraft landing every two minutes, that this is the largest peacetime airlift in the world, and that the weather would be good for our 0933 arrival.

Ha. A tropical depression formed over the Yucatan Peninsula the night before. The forecast for our arrival was 4 miles visibility, 700-foot overcast, and heavy rain. For company, I had asked my flying friend Bill Albert to volunteer his time. He replied with his customary enthusiasm: Yes! With that early takeoff time and since our airplane is based in Tampa, we knew we had to pre-position the night before. We thought we might as well take our wives and have a great meal at Galatoire’s. Our supportive spouses booked flights home on Southwest Airlines.

I was surprised as to how much anxiety this trip triggered in me. I fretted over obtaining pax weights, managing baggage weights (how many bowling balls would there be?), providing N95 masks, making sure the lav was operative—and that we had air sickness bags on board. I scurried to get all this set up.

As a physician, I couldn’t imagine that these athletes weren’t vaccinated, and I found a Special Olympics website that indeed urged everyone to be vaccinated. However, the governor of Florida, Ronald Dion DeSantis, had decreed that the Special Olympics would be fined $27.5 million if vaccines were mandated. The Special Olympics released a statement: “We don’t want to fight, we want to play.” With that, I tried to get to sleep early.

Bill and I left the hotel at 0530 and arrived at Signature Flight Support to find it jammed with athletes and balloons. I paid our fuel bill; everything else—overnight, ramp and GPU charges—had been waived. We met the coach and her athletes.

I preflighted the airplane and at 0640 we walked out into pristine morning sunlight as a brass band played what sounded like Zydeco music. There were at least five other Dove airplanes on the ramp. Two Beechcraft King Airs were already loaded up. I asked the captain of a beautiful King Air 90 if it was hard to land. “You get used to it,” he said. (I want to fly one before I die.)

I gave each pax a warm hello, a hug, a briefing, and a mask. There was no pushback on the masks. I asked each athlete where she was from and they were all representing the state of Louisiana. At 0648 we started up.

We called for taxi at 0650 (five minutes before takeoff) and were told that we were No. 3. A beautiful Citation in brown and gold colors glinted in the sunlight ahead of us. We took off at 0657, two minutes late, not bad considering the amazing coordination that had to take place. We climbed straight east for five minutes but were then told to turn right 50 degrees as we were climbing out of 12,500 feet. Three minutes later, out of Flight Level 180, we were turned back on course. We were already getting vectored to fit into the “Dove flow.”

Though we planned for Flight Level 370 and the fuel efficiency at that altitude, we were never to break higher than FL 330. We sailed eastbound, got shunted north over a bit of Georgia and then joined the SHREK2. The forecast of 700-foot overcast and 4 miles visibility had “improved” to 500 overcast and 10 miles visibility—and rain. That still meant that everybody was going to be doing the ILS to Runway 7.

With multiple heading changes, speed restrictions, and frequency changes, we broke out at 900 feet and saw another bank of clouds at 700 feet. The weather was obviously changing quickly.

I plopped her down at 0954, almost two hours after takeoff. We were martialed to a parking alley. I shutdown, and Bill opened the door. Despite the rain and 60-degree weather, our next impression was the sound of cheering and banging cowbells. Welcome, athletes.

Seconds later, our charges were gone. David Miller, CJP honcho and Olympics force, approached to say, “Hello, old man.” He was in a rain parka and looked vibrant. As I gave the refueling order, Bill raced to the pilot hospitality tent to get out of the wind and sheeting rain.

I sprinted to the tent where I was given a really nice golf shirt that I used to dry myself off. By the time I had ordered a couple of complimentary double espressos and paid the fuel bill, we were ready to take off for home in Tampa. Atlantic Aviation’s impressive line service folks had orchestrated a towing, fueling, positioning sequence.

Safely back home, Bill and I made plans to fly our folks from Orlando back to New Orleans eight days later. It was not to be. The next week, while driving to the airport to fly back to Orlando, I got a call from Zach at Textron. Our passengers had tested positive for COVID; our flight was canceled.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox