An AOG situation means the aircraft needs professional service to make it ready to fly. Until then, it’s grounded. [Courtesy: Dick Karl]

AOG. Aircraft on ground. This phrase strikes horror in the maintenance department. It means the airplane is not flyable. For an airline or Part 135 operator, AOG means lost revenue. Boeing estimates one hour of AOG costs an airline $10,000 to $20,000 dollars, and in some circumstances, up to $100,000 an hour.

AOG means that even though the operator may have an extensive FAA-approved MEL (minimum equipment list) that allows for flight with certain mechanical discrepancies, it doesn’t apply to this situation. An AOG situation means the aircraft needs professional service to make it ready to fly. Until then, it’s grounded.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowI can relate to being grounded as a bone marrow transplant for acute myeloid leukemia leaves a person in an AOG situation. After four months of “consolidation” chemotherapy, I was cleared for transplant at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida. There was some special irony to this as I had served as the founding medical director of the institution and had worked there for more than 25 years before I retired 10 years ago. I hadn’t been back in the building since, but there’s still a picture of me in the lobby from back then when I had hair.

Whereas the consolidating chemo was well tolerated, transplant is another matter. For the first six days I received more chemotherapy and on day five was given total body irradiation.

- READ MORE: That Sound of Music in the Air

On day six at about 2 p.m., a clear plastic bag arrived with donor stem cells designed to replace my own obliterated bone marrow with donor cells. The bag was cold and looked to contain a cup and a half of orange slush, about 7 million stem cells.

About 10 p.m., long after the last cells had been transfused, all hell broke loose. It turned out that my donor cells and my original cells got into a fistfight. Fever, fatigue, and overwhelming weakness prevailed. Cytokine release syndrome, they called it. For the remainder of my 32-day hospital stay I was essentially bedridden—AOG. Since discharge I’ve been doing rehab. They say for every day lying in bed it takes three to recover.

What does this have to do with airplanes? It reminds me that anything can happen, anytime, anywhere. Everything in life is fragile—our health, our machines, our planet.

Aircraft are complex pieces of equipment. A small spill in the lav can lead to a corrosion inspection that might find damage requiring extensive repair, or in some instances, make the aircraft unfit to fly. Even though a previous crew may have felt it left the airplane in fine shape, things happen. My own Part 135 flying experience saw a couple of notable aircraft-on-ground situations..

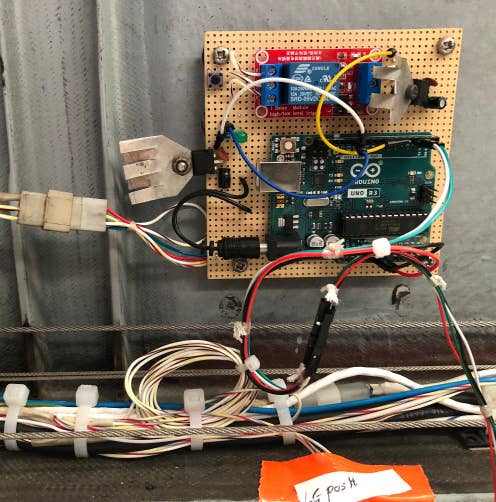

While preparing to fly from Naples, Florida (KAPF), to Teterboro, New Jersey (KTEB), with two passengers in the Cessna CJ3, the flap handle came off in my hand. A surprise! We called maintenance, which was based across the state in West Palm Beach, Florida (KPBI) and dispatch, located in California. A rescue ship was sent to pick up our passengers, and a maintenance tech drove across the state to repair the aircraft while we went back to the hotel. It was expensive due to peak season.

- READ MORE: Riding in the Back of Some Nice Private Jets

Sometimes aircraft damage requires a ferry flight to a more robust maintenance facility. I read recently about a cargo 767 that suffered a hard landing in Portsmouth, New Hampshire (KPSM), with significant structural damage. A ferry permit was issued, and the plane was apparently flown to a major repair facility, but the ferry flight was restricted to 10,000 feet and 250 knots.

I once had to ferry an aircraft for maintenance that had been flagged AOG. It went something like this.

I got a call from the chief pilot, “Dick, you’re the best pilot for this assignment. Actually, you are the only captain available. Someone has drilled a hole in the wing spar of one of our airplanes. The hole is too big to be serviceable, and the airplane has to be ferried to Wichita, Kansas (KICT), from Teterboro, New Jersey. The flight has to be done when no turbulence is predicted and VFR weather is forecast for the departure and destination airport. Tomorrow looks good.”

And so a great first officer and I went to dinner that night, not quite sure what to expect of “holy spar.” The next day as we traversed the country, we joked around by asking each other every few minutes, “You still got a wing over there?”

This column first appeared in the July/August Issue 949 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox