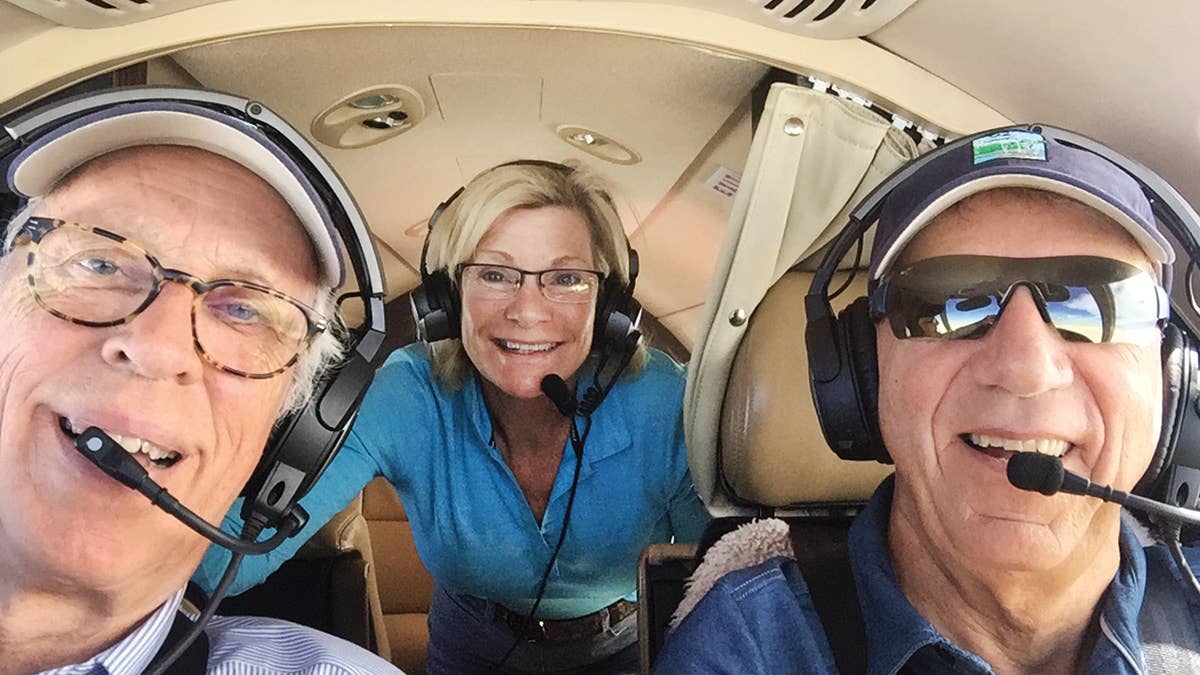

Dick with his generous hosts, Shardel and Pete, somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean in the Cessna Citation M2. Dick Karl

Around here, we call it the “trip of a lifetime,” though that hardly does it justice. You might remember last month’s column that left off at an improbably tasty restaurant in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, after just the first day of a 23-day private jet tour of Europe. Air Journey organized the trip, and it featured three airplanes: two Cessna CJ3+s and “our” Cessna M2. I say “our” because my wife, Cathy, and I were guests of Pete and Shardel, the actual owners of this glamorous Garmin-bedecked M2.

Thierry Pouille and his wife, Sophie, run Air Journey. They accompany or arrange flights for people with capable airplanes and outsize — some might say outlandish — travel dreams. For instance, while we were rambling around some of Europe’s most intriguing destinations, their daughter was shepherding a round-the-world tour. On one day, Air Journey had 18 airplanes in the air. On our trip, Thierry was the briefer, confidant, fixer, slot negotiator, hotel room wrangler and restaurant chooser. I came to look forward to his briefings given the night before a flight. The company, using Jeppesen FliteStar, SkyVectors and ForeFlight, prepared flight plans. Safety, as you will see, was given priority.

There is a lot to say about this trip, but I will confine my description to what I learned from flying in a private jet across the Atlantic and around Europe. I’ll have to tell you about the Red Bull hangar in Salzburg, Austria, and the Pilatus factory in Stans, Switzerland, some other time.

We were up early on day two for the flight from Kangerlussuaq (BGSF) to Reykjavik (BIRK), Iceland, a mere 735 nm. After takeoff, we climbed to 5,300 feet, so as to avoid the rocks, before turning left toward Iceland.

I reported our passage of N66 W040 to Iceland Radio. About the only airport along the way was a 3,934-foot gravel strip called BGKK — whatever that is. I had no desire to find out.

At BIRK, our transition altitude from 1,013 hectopascals to local altimeter setting took place at 7,000 feet. We were cleared for the LOC Z 13 approach, and I was relieved to see the airport come into view as we passed through 1,000 feet msl. The wind was advertised as 170 degrees gusting up to 50 knots(!), but Pete put us on the centerline like a pro. The FBO sported some German Citations and a brand-new TBM 930 with its giddy new owner and ferry pilot getting ready to head west.

Our next destination was to be Amsterdam, but a line of thunderstorms north of the airport dictated a change in plans. Ever been to Norway? Me either, but Stavanger, Norway, was selected for beautiful weather and scenery. Reykjavik to Stavanger (ENZV) is 910 nautical, and we flight planned three hours at Flight Level 410 over the Norwegian Sea. To Pete’s and my enduring satisfaction, we watched the faster CJ3+s fall behind us. At FL 410, we had a slight tailwind; at FL 450 they had a headwind. We were given an unusual view: The Faroe Islands, customarily covered by cloud, were visible, looking all craggy and wind-blown. We set our VHF channel spacing to 8.33 kHz — this would confound me for the rest of the trip. I am just not used to frequencies like 126.705. We beat the others in, parked and waited for the trucks to fuel us all.

I learned about slots and airspace. Amsterdam was still a mess the next day, and no slots were available, so Rotterdam and a bus ride were chosen. Though there are far fewer flights over Europe than there are over the United States, slots and airspace are considerably more precious. Thierry showed me data from 2010 comparing European airspace to the United States. Even then, the United States had 70 percent more controlled flight hours, 38 percent less staff and one en route air navigation service provider (the FAA), compared to 38 in Europe. Our flight plan routes were often curiously nonlinear as we fishtailed our way along, managing to overfly as many countries, and their billable airspace, as possible.

Our next flight, from Rotterdam to Nice, France, was filed for 0900 hours, but we were told upon arrival at the airport that our slot times were starting at 1100. Thierry was on the phone with the tower, urging them to move things along, but to no avail. Our route was anything but a straight line. We traversed the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and France. On flightaware.com, our path resembled a drunk working his way home. We did get a nice view of the Alps though.

Then there are the FBOs. The arrival into Nice was another strange event. We were given a long route out over the Mediterranean Sea, a VOR approach to a point and then a visual. Once on the ground, we taxied to parking ramp Kilo and shut down. A van took our passengers to the FBO (where skin cream could be purchased for 3,500 euros) while we waited in the heat for fuel.

A surprise on departure: The handling fees included 400 euros to hook up a tow bar and push us into a parking spot about 100 feet from where we shut down. The price to tow us back out was another 400 euros. All told, the handling fees, not counting the fuel, were 1,800 euros. A sign in the parking area stated that unauthorized engine or APU start would result in a fine: 20,000 euros. Despite these indignities, the ramp was packed with big private airplanes, all sunning themselves while their owners cavorted in Cannes.

I’ve had a few experiences in the States with remote parking. Usually this inconvenience occurs around popular events like the Masters Tournament or the Super Bowl. In Europe, it can be anywhere. In Salzburg, Stavanger, and Tallinn, Estonia, our airplanes were parked nonwalkable distances from customs and fuel providers. We were dependent on vans and fuelers to come to us. Note to self: Don’t leave anything in the airplane that you might want later on. Are you sure the battery is disconnected and the brakes are off?

Most of the approaches were ILS or visual. We had very good weather, for the most part. At some airports, large mountains are situated close to the field, and in some places takeoffs and landings were in opposite directions to avoid the peaks, if winds permitted.

Controllers were almost always easy to understand after a few minutes of acclimation. For some reason, I found the Italian controllers to be the easiest to hear clearly — maybe because I grew up in New York.

Our destinations also included Ljubljana, Slovenia; Saint-Louis, France; Tallinn (cheapest fuel at $2.96 per gallon); Stockholm; and Edinburgh, Scotland (by happenstance, we had drinks there with Flying senior editor Rob Mark and his wife, Nancy — what were the chances?) before heading back across the Atlantic via Iceland, Greenland and Canada.

Some 21 legs and 40 hours after setting out, we were home. There’s lots to see and admire in Europe; the culture and beauty are memorable. But I found myself deeply grateful to be back at my home FBO in Tampa, Florida, where they all know my family and me. I can walk out to the airplane and get in and go anywhere in these United States and talk to one ATC system and not (yet, anyway) get a bill for the privilege of flight across this great land.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox