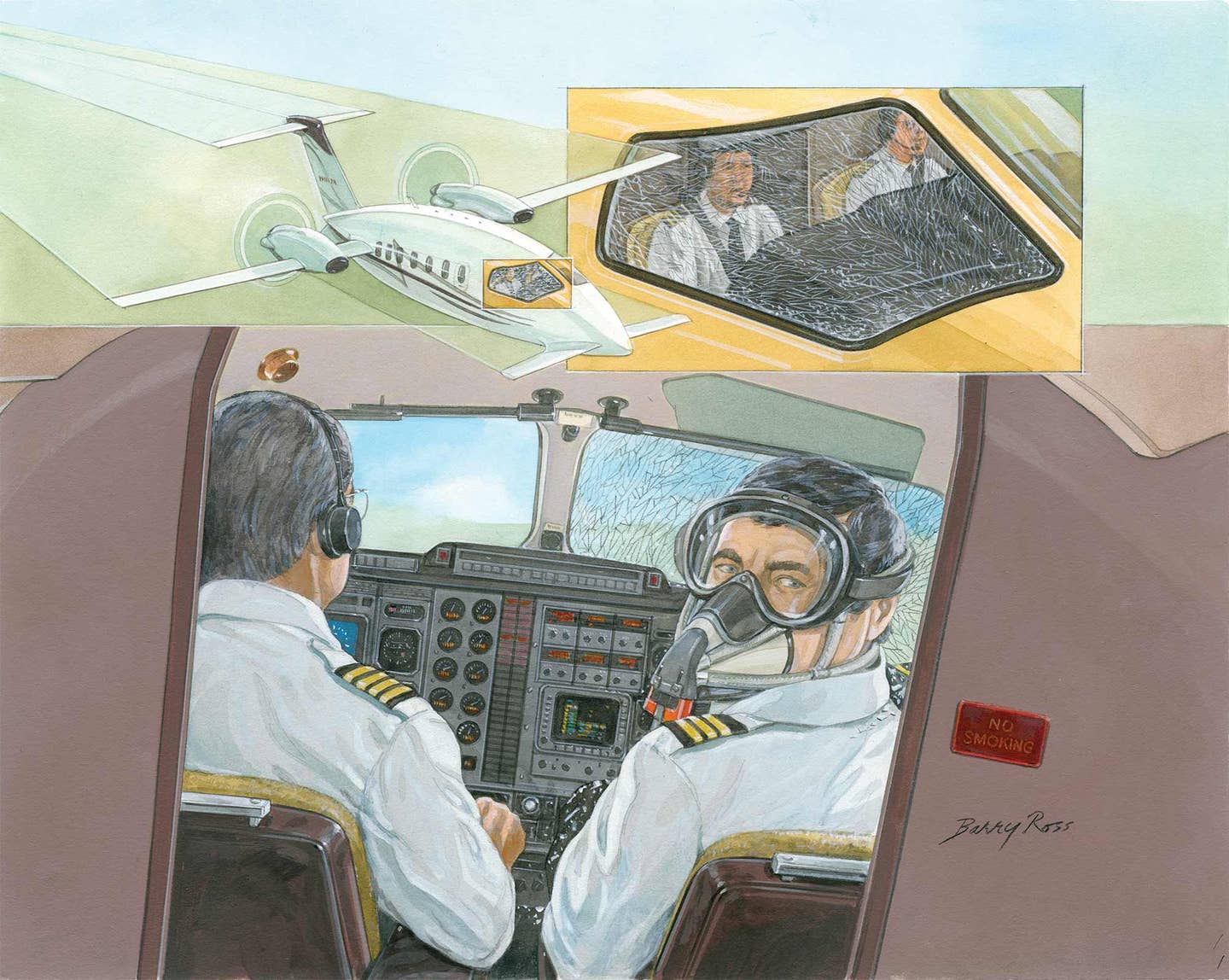

A flight to Memphis in a Piaggio Avanti ended up having a lasting influence on one pilot’s entire career. Barry Ross/BarryRossArt.com

I was irritated to receive a phone call assigning me to a flight the next day, which was both my wedding anniversary and Thanksgiving, but such is the life of a charter pilot.

I would be riding right seat in our Piaggio Avanti with its regular captain, Mike, taking a family on a last-minute flight to Memphis, Tennessee, for the holiday. Little did I know just how much of an influence that one day would have on me throughout the rest of my career.

Moving into professional aviation in my mid-30s, I had become a CFI four years earlier, and had just about completed my first year of employment as a pilot for a local charter company. I had also just completed my first “school,” Beechcraft King Air 200 Part 135 simulator initial training. While not current in the Piaggio, I was asked to ride along in the right seat of this single-pilot turboprop as an observer and to help out.

Despite my annoyance of having my holiday plans ruined, I painted on my best smile for the passengers as they boarded. Three generations climbed on board, including their latest edition, a little baby girl. Every seat was filled as we launched from Houston on what we assumed would be another routine revenue flight.

The Piaggio is quite an unusual-looking airplane (the line service guys say it looks like a catfish), but it’s a stellar performer, yielding 100 knots more airspeed than a King Air with essentially the same engines. In addition, the ceiling is a surprising 41,000 feet. No doubt, much of this is attributed to its sleek design, with a forward wing, aerodynamically designed fuselage and a unique main wing, which has less surface area than that of a Cessna 172.

Takeoff, climb and cruise were uneventful, and before long, it was time to start down from our cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. As we passed 29,000 feet, there was a loud, muffled bang, which I actually felt on my face. At that moment, the entire windscreen in front of me shattered, with no pieces larger than a fingernail. It stayed in place, and we did not seem to be losing cabin pressure, but every few seconds it made crunching noises as shards of glass dropped on me from head to toe.

I distinctly remember my first thought being, What the heck? followed shortly thereafter with, Oh, crap! A second after that, my brain came back to life and my recent training kicked in.

The drama in the cockpit was clearly visible to the passengers, who all sat with terrified expressions, staring forward into the cockpit. I turned to them and told them to relax, fasten their seat belts and put the oxygen masks on when they dropped from the ceiling.

The Piaggio windscreen comes in two pieces: left and right. When viewed from the cockpit, it extends several feet in front of you, up to the top of your head, and wraps around to the side. The continued breaking and falling shards of glass left us with little doubt that it was going to blow in at any moment.

Mike looked over at me and suggested that I put on my quick-donning mask and smoke goggles for protection for when the windshield hit me in the face at 300 knots.

Communication while wearing oxygen masks is possible, but difficult. Mike said he was going to leave the autopilot on, in case we were incapacitated, and not put on his mask so long as we retained cabin pressure to aid in his being able to talk to ATC. The silence in the back was broken by one of the female passengers exclaiming, “Oh my God, he’s putting his mask on!” About that time, I could hear Mike declaring an emergency on the radio.

Our descent continued, and Mike had further told me he had a good visual on the freeway below in case we had to attempt a landing on it. Since the fuselage makes up some percentage of the Avanti’s lift, we weren’t sure how it would even fly with a missing windscreen. Furthermore, Mike had decided against a traditional “emergency descent” and was instead maintaining his descent speed while slowly raising the cabin pressure. He explained that he didn’t want to increase the force on the outside of the glass with airspeed, or the force on the inside with cabin pressure.

There is an eternity of silence that fills an airplane in an emergency once you’ve done everything there is to do and you are waiting to land. I looked back to check on the passengers and noted that they had passed the infant to the back, covering her with a stack of blankets. They were all grasping hands and praying. Our descent profile put us right at our destination, KMEM, so it seemed logical that unless something changed, we would go ahead and land there. Such was the case, and about 25 minutes later we touched down without incident. Once on the taxiway, I removed my mask and goggles while the passengers cheered us from the back, bringing to a close my first true in-flight emergency in a turbine-powered airplane.

Much was learned from this incident, except why the windscreen shattered in the first place, which remains a mystery. I appreciated Mike’s calm demeanor in handling this event, and have since learned that much of what goes wrong in an airplane is something you haven’t trained for.

Simulator instructors will give you an explosive decompression, not a broken windscreen, faulty controller or failed environmental plumbing, which seem to be the leading causes of pressurization problems. There was no checklist guidance concerning the windscreen, and training at the time didn’t talk about the various panes of glass involved in its construction (ours was only a shattered inner pane, and not the stronger outer pane).

System knowledge is as important as researching other incidents in the same type of airplane. In fact, an integral part of any professional training event involves sharing experiences with other pilots. One must always be ready to think outside the box, and be ready for when a rare problem presents itself and there is no guidance on how to handle it.

Likely the most important lesson I learned, which I employed just recently while again dealing with a pressurization issue, is prioritizing your actions.

First, take care of yourself (seat belts, oxygen, goggles, etc.).

Second, take care of your airplane (maintain control, initiate descent, autopilot on, etc.).

Third, take care of the passengers (brief them, deploy masks, etc.).

I have found that these priorities are a prescription for success no matter the type of problem that presents itself.

The longer I fly, the more I realize that the learning never stops. Whether they are related to human factors, the operating environment or inherent to the machine itself, there are too many variables at play when flying airplanes to ever consider them all.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox