Fairchild XC-120 Packplane Became an Intermodal Hope That Fell Flat

It was designed with ‘quadricycle’ landing gear and modular cargo pod that, in theory, could be quickly attached to and detached from the aircraft.

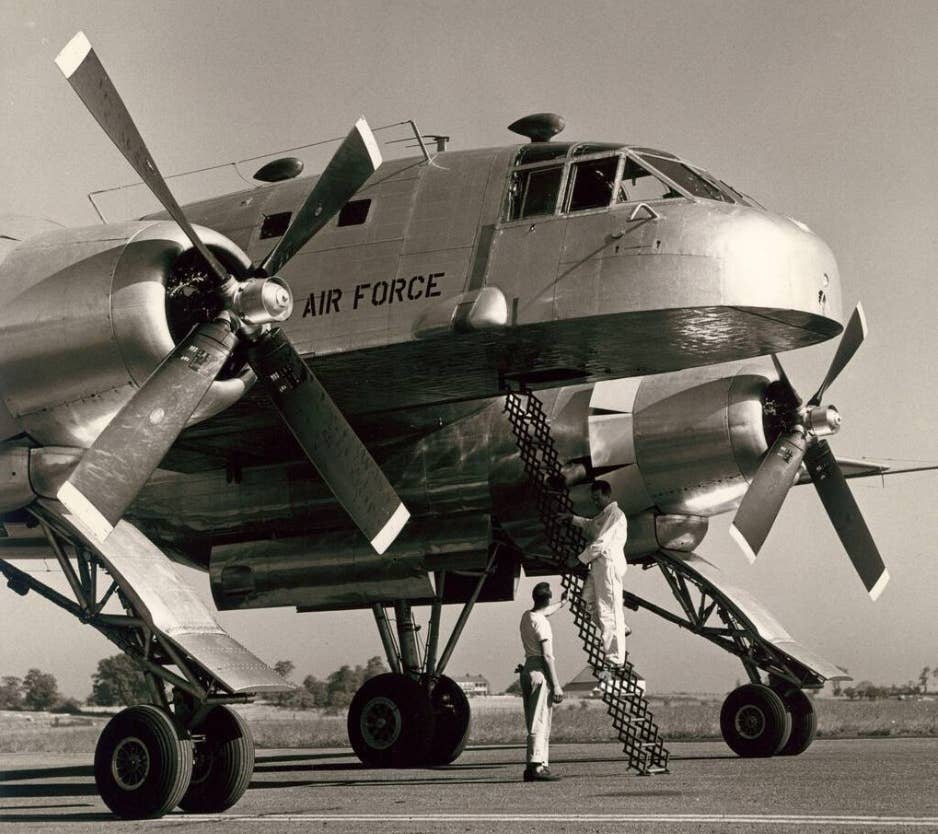

With the detachable cargo pod removed, personnel boarded the unique Fairchild XC-120 via an extendable ladder. [Credit: U.S. Air Force]

In the years following World War II, aircraft manufacturers and militaries alike were in search of new and innovative solutions to transporting cargo and personnel into and out of war zones and around the world. With stalwarts like the Douglas C-47 setting the bar high, Fairchild rose to the challenge, developing the C-82 Packet and its improved successor, the C-119 Flying Boxcar.

These new designs incorporated then-modern tricycle landing gear and, notably, rear cargo ramps to expedite the loading and unloading of vehicles and outsized cargo. However, when the logistics behind the delivery of troops and supplies were explored from a higher level, an innovative new concept emerged.

Recognizing that the loading and unloading process could become lengthy and keep aircraft on the ground for inordinately long periods of time, Fairchild engineers devised an unconventional solution. Starting with a C-119, they removed all but the top sliver of the fuselage and created entirely new “quadricycle” landing gear. They also developed a modular cargo pod that, in theory, could be quickly and easily attached to and detached from the aircraft. The insect-like aircraft could fly with or without the cargo pod and was named the Fairchild XC-120 Packplane.

The concept was similar to that of intermodal cargo containers. Ground crews could take their time loading and unloading the cargo pods on the ground, separately from the aircraft. When an aircraft arrived, crews could quickly disconnect the cargo pod it was carrying and reattach a preloaded pod in its place. This would minimize the amount of time the aircraft spent on the ground, theoretically moving more cargo over the course of a day.

The XC-120 was an interesting aircraft. While it offered the capability of carrying the custom cargo pods, the extreme modifications differentiating it from the C-119 introduced some technical and performance limitations.

The quadricycle landing gear, for example, solved the problem of loading and unloading the cargo pod but presented new problems, particularly with ground towing. Special equipment was required to keep both front wheels tracking parallel to each other when backing up. This equipment could be carried in a pod but had to be left behind when flying without a pod attached. The unique landing gear also precluded “power backs,” or utilizing reverse thrust to back the aircraft up on the ground.

Aerodynamically, it also presented some challenges. Test crews discovered insufficient lateral and directional control at low speeds. Notably, during takeoff, the aircraft’s left-turning tendency could not be overcome by full right rudder. Their solution was to utilize asymmetric power until reaching 35 knots, at which point full power could be applied. The unique landing gear also had to be retracted immediately after liftoff, as it produced large amounts of drag during the retraction sequence.

Surprisingly, the speed penalty for the pod was minimal. Flight test reports indicate that at a power setting of 2260 BHP, the XC-120 with a pod installed cruised at 218 knots—only 14 knots slower than flight without the pod. As the pod weighed approximately 9,000-10,000 pounds, some of this penalty could have been a function of weight as opposed to aerodynamics. Test pilots also noted that the wheel-well doors were hanging approximately one and a quarter inches open in flight during the entire test program, but this would have been the case with or without a pod attached.

The additional drag of the gear doors undoubtedly contributed to the lackluster single-engine climb performance. With the pod attached, the absolute ceiling with one engine inoperative at 63,000 pounds (1,000 pounds below maximum takeoff weight) was only 3,300 feet. Under the same conditions, the maximum rate of climb at 2,000 feet was between 10 and 50 feet per minute. While no mention of jettison capabilities was made regarding the cargo pod, it’s not difficult to imagine scenarios in which flight crews would wish for the feature.

Despite the theoretical advantages of the modular pod concept and the military’s limited success with a similar concept with Sikorsky Skycrane helicopters, the benefits didn’t come entirely to fruition. Evaluation crews discovered that attaching or removing the pod required an “unusual” amount of time due to the slow hoist mechanism, and doing so in high or gusty winds proved challenging, requiring even more time.

The lackluster reception of the system and inherent logistical challenges proved insurmountable. In 1952, only a couple of years after the XC-120’s first flight, the program was canceled, and the sole XC-120 was ultimately scrapped.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox