Listening to That Inner Pilot Voice

Consider the lesson learned when it comes to ignoring the warning sign of an impending failure.

When the little pilot voice says, ‘all is not right here,’ pause to evaluate what’s going on. [Image: Joel Kimmel]

My story begins with two preliminary events, each with a clue as to the nature of the main event.

First, in April 1996, I had spent an hour in recurrent training in my Skyhawk. We had done some air work, including steep turns and slow flight, as well as some partial panel flying. As we returned to the Purdue University Airport (KLAF), my instructor suggested a no-flap landing, something I had not practiced since primary training nearly 10 years previously. It went well, and I was reminded that no-flap landings are faster and with a more nose-high attitude.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowSecond, a few days later I went with my daughter’s preschool class to visit the KLAF tower. The day was solid IFR with little activity, so the tower controllers had to be creative to entertain 15 5-year-olds. They brought out the light guns and the kids were captivated.

The main event occurred a few days later when my wife, daughter and I flew to Kalamazoo, Michigan (KAZO), on an early Saturday morning. We had made this trip many times, and it proved the utility of a small airplane. Instead of spending seven tedious hours on the highway to spend five hours with my wife’s family, we spent three pleasant hours in the air to spend nine hours with her family. The flight was easy, we had a relaxing day with my in-laws, and in late afternoon we returned to the airport for the flight home.

The walkaround was normal, the tanks were full, and with a forecast for “severe clear,” we were set for a relaxing flight home. On the run-up pad with the engine to 1,700 rpm, the mags checked out, and the oil pressure and suction were in the green. The ammeter showed a discharge with the landing light turned on and returned to center with the light off—well, maybe not completely center but close enough. After all, many a CFI had complained that these gauges in Skyhawks were not precise. A small voice in the back of my head said, “Hmm, maybe I should investigate that,” but I ignored the voice and we departed.

On our IFR flight plan, as I spoke with air traffic controllers, the radio seemed scratchier than usual, but this was probably just some random electrical glitch, right? No. Just as the sun was setting, we lost all electrical power—no radios, no transponder, no lights, and, of course, no flaps.

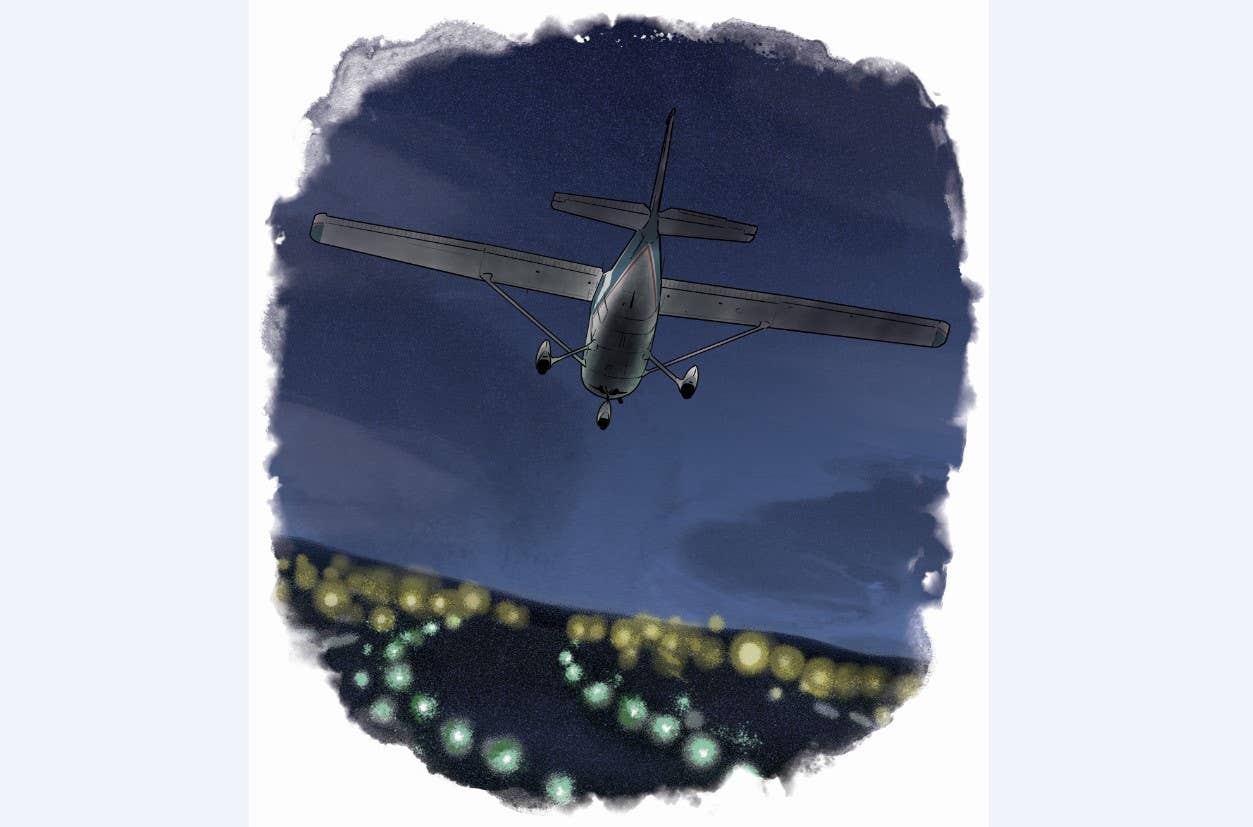

This happened as we were about 25 minutes from KLAF, but we were directly over a small airport where I had frequently practiced touch-and-goes. I told my wife that we could land immediately—without flaps—but otherwise all would be straightforward, and we could call a friend to fetch us. Alternatively, we could continue homeward. I explained that although ATC had lost our data block when the transponder lost power, the primary return was still visible on radar, moving steadily to KLAF. Chicago Center would tell the KLAF tower that a NORDO was inbound. We would fly 1,000 feet above pattern altitude, looking for the steady green light that meant we were cleared to land.

My wife said that we should go ahead to KLAF. I was grateful for the vote of confidence. I grabbed my flashlight so that I could see the instruments and on we went. And it worked out exactly as I had told her: We approached KLAF above pattern altitude, saw the steady green light, entered the pattern, and made an easy landing in the dark with no landing light and no flaps. (And it was really dark—when we left KLAF that morning, I was wearing my prescription sunglasses and had left my regular glasses in the car in the hangar). After we had put the plane in the hangar, I called the tower and thanked the folks for their help. They confirmed that Chicago Center had forewarned them of my arrival and that they had alerted everyone in the pattern to be especially vigilant.

On the drive home, I reflected on the evening’s events. On the one hand, I was pleased that I had handled the emergency calmly and by the book. And I was grateful that the event had occurred in familiar airspace with no additional challenges associated with bad weather. On the other hand, I was annoyed that I had misread the signs that led to the emergency.

What did I learn from the episode?

First, periodically expand my scan of the panel to include instruments, such as the ammeter, that are on the far side of the panel. Second, receive recurrent training regularly to get feedback from a CFI about skills that may have grown rusty and should be practiced. Third, use the ATC system. These folks provide great service that can simplify a pilot’s tasks and can be a tremendous asset in an emergency. Fourth, when there are signs that something might be wrong, don’t weave a story to explain and then dismiss those signs. Instead, when the little voice says, “all is not right here,” pause to evaluate what’s going on.

Finally, keep a spare pair of glasses in the flight bag!

This column first appeared in the July/August Issue 949 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox