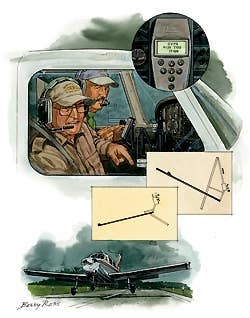

It was a dark and stormy night in late October. George, one of five partners in our Warrior, and I were completing the last leg of a three-segment flight. Our purpose, other than practice and fun, was to test out our brand-new yoke-mounted Trimble GPS that we had just acquired. The GPS was replacing a tired and totally unreliable Loran C that we had installed years earlier. We had chosen three airports spaced in a triangle about 100 miles apart to give us a good test of its capabilities. So far the Trimble had been spot on, shepherding us from airport to airport. This was a far cry from the loran, which would display inaccuracies of up to 20 miles. George and I had talked the other partners into spending $2,000 for the new GPS, and at this point we were feeling pretty good about our decision.

The first two legs had been smooth as silk and the weather had cooperated, giving us cloudy but otherwise fair skies. However, on this segment we were encountering darkness, lowering cloud, the odd bit of fog and occasional light rain that would pepper our windshield. Still, with nearly 50 years and 2,000 hours of flying time between us, we felt comfortable and very confident in our ability to complete a safe flight. Cocooned in our David Clarks we talked casually over the intercom about a number of subjects, including the capabilities and features of our new acquisition. We were also getting very comfortable in the operation of our new GPS. Below us widely scattered lights from the farmhouses flickered as small areas of fog and haze passed. Other than the steady drone of the engine, it was unusually quiet with very little radio traffic. As the flying pilot I had just informed George that we were within 20 miles of Peterborough, our destination airfield.

Suddenly George let out a gasp. "Peterborough Airport is right below us!" he exclaimed. "How could it be?" I countered. "The GPS says we are still 17 miles away." However, I looked at the ground below us and sure enough, there was the airport directly off our right wing. I immediately started a left turn in order to set ourselves up for the downwind leg. At the same time I changed our radio to 123.0, the Peterborough Unicom frequency. Over the field now and preparing to enter downwind, I broadcast our position and intentions, not really expecting a response considering the weather and the late hour. Out of the darkness a voice came over the radio. The voice came from a pilot who was at the threshold of the active runway at Peterborough. He volunteered to hold position until we touched down.

All the while George and I were beating ourselves up over the fact that we had talked our partners into installing this "piece of garbage." We lamented that we were no better off than we were with the loran. What is it about this area of Kawartha Lakes that will screw up compasses and electronic navigation equipment? Is this the "Bermuda Triangle" of Ontario? How are we going to explain to our partners that we just wasted $2,000 of their money?

By this time we had entered the final approach. After announcing our position, the waiting pilot asked us to display our landing light. Knowing I already turned the landing light on, I offered to cycle the light. Still the waiting pilot could not locate us. We could detect frustration in the other pilot's voice as he strained to see us. As we continued our approach I again announced short final when we were about 1,000 feet from the pavement. The other pilot acknowledged, and in an obviously stressed voice he stated that he still could not see our landing light. George commented to me that maybe this pilot should not be flying in these conditions with his flawed eyesight. What followed was one of my better landings, a real greaser.

After rollout we announced, "Backtracking 27," but now there was no answer from the waiting traffic. As we turned onto the ramp we could see no other aircraft. Where had the other airplane disappeared to? Suddenly out of the darkness a sign appeared. "Welcome to Lindsay Airport, Altitude 882 ASL." George and I looked at each other with utter disbelief. Several emotions hit me all at once. Relief that our new GPS was working properly after all. Embarrassment that we had just done the unthinkable. Shame about what if our partners and other pilot friends found out what we had done. And apologetic about the other poor pilot still sitting at Peterborough waiting to take off.

George and I made the decision to take off immediately and at least try to contact the other pilot to explain our mistake and apologize for keeping him on the ground. Unfortunately, after takeoff we could not contact the other pilot. Obviously he had left during the almost 10 minutes and was now on another frequency.

How could two very experienced pilots have made such a gross error? There were numerous and obvious clues to point out our mistake. Any one of them, if we took the time to think, would have clearly shown us that we were at the wrong airport. First and foremost, the GPS told us that we were 17 miles from Peterborough. Because of our experience with the loran, we automatically assumed that the information was wrong. Second, there were visual clues like buildings and plazas that were close to Lindsay Airport, but none were located near Peterborough. The poor visibility could have contributed to this oversight. Third was the fact that the other pilot could not see our landing light, when he clearly should have seen it. Fourth was the fact that the Lindsay runway number is 31 not 27. Also the Lindsay runway elevation is over 250 feet higher than Peterborough's elevation. This error if made in hard IFR conditions could have been fatal.

We had made a classic mistake that has caused numerous accidents. This mindset was the cause of an airline accident several years ago, in which the pilots flew their aircraft into the ground while they were diagnosing a burned out light bulb in their instrument panel. More recently an airliner almost ran out of fuel in the middle of the ocean, because the pilots were convinced that the low fuel indications were caused by a computer malfunction, instead of a major fuel leak. Yes, we had become so fixated with our impression of an instrument problem, that we ignored several clues that were screaming at us. Both George and I have spent our whole careers as officers in the emergency services. We are used to making life and death decisions on a daily basis. We are used to working under extreme pressure. Everyday we have to deal with complex situations and in the midst of chaos, find a logical solution. In this instance we had gotten away with a major error with only our egos bruised.

Our experience gave us a new insight and understanding as to how a pilot can convince himself that something makes sense, when in fact all the clues suggest otherwise. The moment that I bought into George's argument, that our destination airport was below us, we went through a process of mutually reinforcing the bogus reality. Together, we ignored all clues that didn't fit the picture we had so conveniently accepted. NTSB has numerous examples of unsolved air crashes, where aircraft have inexplicitly flown into the ground while under control (CFIT). Could this be an example of how such a thing could happen? I now have a new appreciation for the fact that any pilot or crew can make this type of mistake.

Although this incident happened several years ago, I think that the experience made us better pilots. It may have even made us better fire officers. We swore on that day that we would never again ignore even the smallest clue that something was wrong. If you are performing a task, no matter how complex, and even the smallest detail doesn't fit the picture, you should pause, go around, abort or take whatever action is necessary. Fly your aircraft into a safe and stable position, so that you can reevaluate the situation. This will allow you to take the time to carefully analyze factual information you have at hand and separate truth from suppositions. Never become so fixated on a problem that you handicap yourself as a pilot and endanger your passengers. These are lessons that we will never forget.

During dark and foggy evenings, when a cool wet chill is in the air and you can hear wolves howl in the distance, pilots at Peterborough Airport will sometimes gather around the hangar to tell the story about the night that the 'Ghost Ship' landed at Peterborough.

To see more of Barry Ross' aviation art, go to barryrossart.com.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox