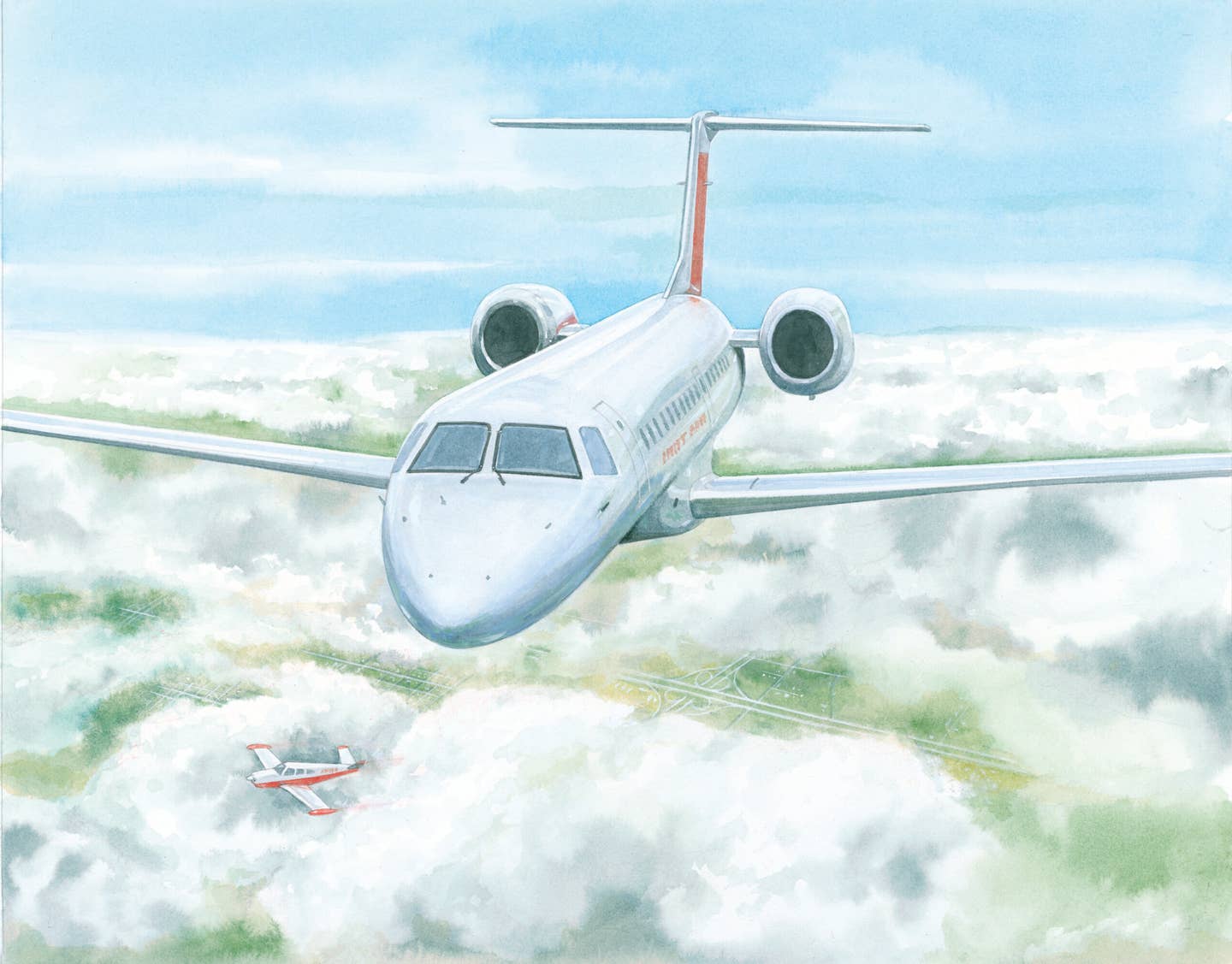

To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go to barryrossart.com Barry Ross

Through the years, I have enjoyed relating to ILAFFT stories in Flying and have even corrected a few bad habits based on what I’ve read. I thought there would come a time when the lessons I personally learned while flying would no longer translate to GA flying, and my window of opportunity to submit to this department would close. That view was proved wrong on July 27, 2016.

I am a five-year first officer with my current airline, flying the Embraer 145 out of Chicago O’Hare International Airport. I would not say I am a “very” experienced pilot, but my flight time is around 5,000 hours, the last 4,000 of which have been at the airlines. Now, I know we never stop learning. I had a saying for my CFI candidate students: “If you ever show up one day thinking you know it all, quit.” I carry that same principle over to my current job, and still preach it when I can.

The day was beautiful by all accounts: a moderate 85-degree temperature with some scattered and broken clouds at 4,000 feet across the Midwest. My captain and I were set to blast off for our last flight of the day to La Crosse, Wisconsin, for our overnight. During our normal banter and preflight preparations, I mentioned that Oshkosh was going on next week and that I couldn’t wait to head up for a day trip. I also mentioned that we should probably keep an extra-cautious eye out on descent, as there might be additional VFR traffic inbound to the world’s greatest aviation celebration. How right that would be.

My captain, Heather, and I had flown together many times before, and we both had a healthy respect for each other in the airplane. We got along great, whether performing our duties or discussing life in general. Heather is knowledgeable about the job, a pleasure to talk to, and kind to those around her. Anyone flying in a crew environment can tell you that those are qualities highly coveted in a partner when you are spending four days in close quarters. As is normal in our line of work, we took turns flying the airplane. On this leg, Heather would fly us up to Wisconsin.

The flight departed normally enough. We reached our cruising altitude of 21,000 feet in about 15 minutes for our quick 40-minute flight. The conversation settled into normal discussions for flight crews: food, company politics, overnight distractions and funny stuff on TV. About 100 miles from La Crosse, ATC issued a descent to 4,000 feet and cleared us direct to La Crosse.

Heather dialed in the altitude, and we both verbally stated that the correct figure of 4,000 had been set. As would prove to be vital later, she then selected “direct to” on the FMS, and we pointed the nose at KLSE. About 30 seconds went by before I realized that we were not descending. Thinking for a moment about whether ATC had given us “pilot’s discretion” or “descend to,” I decided to verify with my captain.

“Are we supposed to head down now?” I asked. I take the Dale Carnegie method of suggesting instead of pointing out an error. It works great in life, but is even more important in crew resource management. Nothing will inhibit solid crew resource management faster than sounding as if you are pointing out a flaw and are disappointed. Let your fellow pilot get there on his or her own with a gentle inquiry.

“Oh, shoot. Yep,” Heather said. All better, we started our descent. In the back of my mind, I figured we would be safe from traffic until we descended below the clouds. According to the latest weather in La Crosse, the cloud layer was about 3,000 feet agl, and we would be descending right into it.

Looking out the window, I was guessing that the clouds were at least scattered and maybe even closer to broken as we made our way north. Given those conditions, anyone above the clouds would probably be on an IFR flight plan, and certainly everyone in the clouds would have to be on one — right?

We continued down through 10,000 feet and finished the checklists and other tasks. About 2,000 feet above the cloud layer, I was looking at the approach plate (OK, it’s an iPad now) for a verification of a frequency. I looked up and caught a quick glimmer below and to the left of the windshield. Taking a second to realize what I was seeing and process the situation, I made the call to the captain in a calm but determined voice: “Traffic. Dead ahead, below 1,000 feet, level.”

“Got it,” Heather replied.

Heather reached up and took control of the aircraft, disengaging the autopilot to level the plane. Both our eyes were staring down on the offending traffic. Judging by the airplane’s lack of course change, we guessed the pilot never even saw us. The aircraft passed by to our right and low. I verified that there was no traffic depicted on the TCAS and queried ATC.

“Hey, Approach, do you have anyone out here on your radar?” I asked.

“Um, nope,” the controller replied.

“OK. We just passed a Bonanza heading northeast right at or in between the clouds. Negative transponder,” I said.

“Oh yeah, I saw him as a primary target but didn’t think anything of it,” the controller replied.

With the plane safely behind us, the captain and I shared a nervous laugh. As we reconfigured the airplane to continue our descent, the reality set in: If we had started down from cruise right away, maybe it would have been closer. If we had not had the thought of increased traffic vigilance in the back of our minds, maybe we wouldn’t have responded as quickly as we did. Our passengers might not have made it the rest of the way home.

And then the questions: Why was that airplane flying without its transponder on? Why was that pilot in and out of the clouds if he didn’t have a transponder? Why did ATC not think to at least mention that they were showing a primary target?

As I thought more about those questions, I realized it didn’t matter what the answers were. The procedures we learn from primary training all the way to the highest ratings are emphasized not for when things are ideal, but for when things are not. In this case, I had made an assumption about where aircraft would and would not be. Automation (TCAS) had convinced me that it would show me anyone flying around in the clouds. I had relied on others — ATC and other pilots — to be on top of their game.

Following the “Swiss cheese” model of risk management, I had allowed myself to assume a lot about the environment around me and relaxed my scan. Was I safe or was I lucky? Sure, we had thought about the increased chance of traffic, but did we really believe we would see anyone? Since then, I have spent much more time with my eyes outside, and have even brushed up on my scanning technique. And hey, we all got into this flying thing because of the view, anyway!

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox