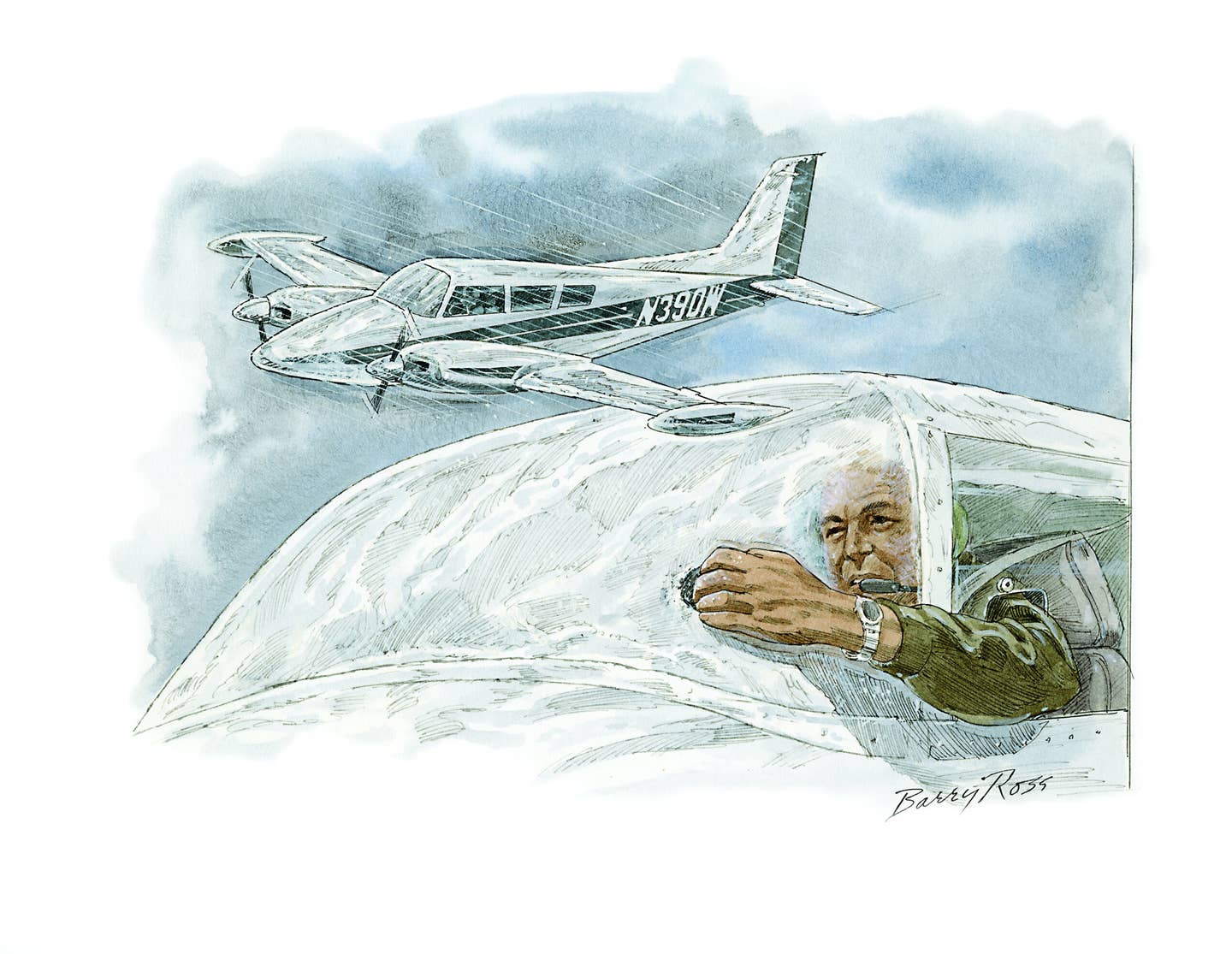

To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go to barryrossart.com Barry Ross

The occasional audible swoosh of ice departing the propellers and the bang of that ice hitting the fuselage provided the only comforting moments of this flight. How did I get here? Countless times when growing up I would look up from the ground at an airplane flying overhead and wish I were up there. This was the first time while flying that I wished I were on the ground. Would I return to the Earth again without incident? In all my years of flying I had never doubted the outcome of a flight more.

A classic pilot lesson is the old saw about the two bags we all have: one bag to fill with experience, and the other bag filled with an unknown but finite amount of luck. Every time pilots fly they must dip into one of the bags. The goal is to fill the bag of experience before emptying the bag of luck. I try to avoid dipping into my bag of luck, but today I was just hoping it wasn’t empty.

My IFR flying experience began and was increasing steadily in the early 1990s. As a project manager for a utility building high-voltage power lines in upper Michigan, I flew the round trip about twice a week from my home in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. With one exception, my little radar-equipped, turbocharged Piper Twin Comanche was well suited for the mission. That one exception was the lack of deice boots. The alcohol propeller system was the airplane’s only deice capability. The swoosh and bang sounds on this flight assured me that system was keeping the props clear of ice.

I had been looking forward to this very different trip, escaping the cold of the Midwest for island hopping in the warm Bahamas. The plan was a short flight from Milwaukee to northern Illinois to pick up my son and daughter, then on to Fort Pierce, Florida, and then off to the Bahamas. The forecast was warmer air entering southeast Wisconsin, ceilings 2,000, tops over 10,000, possible icing at 6,000 and above. Thankful to live in the Midwest where one can file IFR well below 6,000 feet, I hoped that I might be able to make the 25-minute first leg in visual meteorological conditions below the overcast.

Upon arrival at the airport, the tower beacon let me know the ceiling was not as forecast and was instead below 1,000 feet. While pulling the airplane out of the hangar, a few brief ice-pellet showers passed through, making the ramp very slippery. However, the surface temperature was below freezing and no precipitation was sticking to the airframe. The ice pellets were also not in the forecast and should have alerted me that the weather would not be as briefed, and I should call for an update.

The flight was normal through takeoff, and as I entered the overcast, tower handed me off to departure. Upon entering the overcast, ice began building on the aircraft.

“Approach, Twin Comanche 390Y, off Waukesha, passing 1,500 for 3,000. I’m picking up ice and would like to expedite climb to 4,000.”

“390Y Milwaukee, Approach, climb and maintain 3,000, heading 180.”

My strategy against icing had been to use the turbos to climb above the icing band, but I soon learned that other aircraft were still picking up ice all the way up to 10,000 feet.

It didn’t take long for the ice accumulation to become serious, and I decided the best course of action would be to return and wait for better conditions.

“Approach, 390Y would like to return to Waukesha.”

“Twin Comanche 390Y, Approach, be advised you will be number six for the approach.”

Number six? The frequency was full of calls for help due to the ice. A Bonanza that was number one for Waukesha had already declared an emergency.

If the ice accumulation continued at the current rate, I doubted I could wait much longer, so I decided it would be quicker to continue to my filed destination.

“Approach, 390Y would like to continue to DeKalb rather than return to Waukesha.”

“90Y, Milwaukee Approach, roger, maintain 180 heading and I will have lower for you in 10 miles.”

A few minutes later Milwaukee cleared me to its minimum vectoring altitude (MVA). The controller had several planes at MVA. He kept making contact with each one in sequence. “Cessna 65C, Milwaukee, how are you doing? Piper 74P, you are next for the approach at Waukesha. Twin Comanche 390Y, how are you doing at 2,300?”

How am I doing? Not great. The ice pellets and lower ceilings were warning signs — signs that filled into my bag of experience that might help on a future flight, but which were too late for this one. I had gone full alcohol flow on the prop deice, full climb power and high takeoff rpm. The windshield had been covered since shortly after takeoff; looking out at the wings, the ice (or super-cooled rain) seemed to bounce as it hit, causing a horned ice formation on the leading edge. I was maintaining altitude, but now I was down to 115 knots, more than 50 knots slower than I should have been with this maximum-climb power setting. But the good news was that I was no longer picking up additional ice.

I was also getting an occasional glimpse of the ground through cloud breaks. That made me feel a little better.

“Twin Comanche 390Y, contact Chicago Center on 134.12,” the controller said.

Once cleared for the approach at DeKalb, I left the power up, flaps up, and planned to hold off lowering the gear until I picked up speed, descending on final.

Full windshield defrost was no match for the ice, and at the time DKB had a VOR approach that flew you past the end of the threshold at an angle to the runway. I’d have to see out my ice-covered windshield to at least line up with the runway, and I didn’t dare slip with this ice load. I opened up the little side vent window and stuck my hand outside. It was really cold, but I managed to scrape a hole in the ice with my fingernail the size of a half-dollar coin on the windshield. There’s the runway!

The small clearing I made in the windshield was too small to make the landing flare. However, I had some experience in the flare with limited forward visibility flying radial-powered taildraggers — score one for the bag of experience. I planned to use my peripheral vision to look out the side windows, pull back power, and flare just like I had to do in taildraggers, even with a clear windshield.

Approaching the runway, I reduced the sink rate, but kept the speed up. I rounded out and didn’t pull the power back until I was a foot above the runway. The landing was uneventful, but the braking on the runway was poor due to a coating of ice. I taxied up to the FBO using differential power. Folks came out to look at the sight of the Comanche loaded down with a ton of ice. It was actually embarrassing, but I was thankful to be back on the ground in one piece.

Six hours later, the warm air front passed. I climbed out into a clear starlit night, heading for Florida with a strong tailwind. I thought of the previous flight, earlier that day. I was forced to dig deep into my precious bag of luck. Had luck run out, things could have easily turned out far worse. Loaded recently into my bag of experience were triggers for rechecking the weather; weather below the forecast or weather not in the forecast — like ice-pellet showers. And the experience of recognizing the potential icing effects of a warm air mass pushing over a cold air mass.

Everyone else on board was now asleep. What a tailwind I have tonight, I thought. Life is good. Tomorrow afternoon we will be on a warm Bahamian beach and the only ice will be in my drink.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox