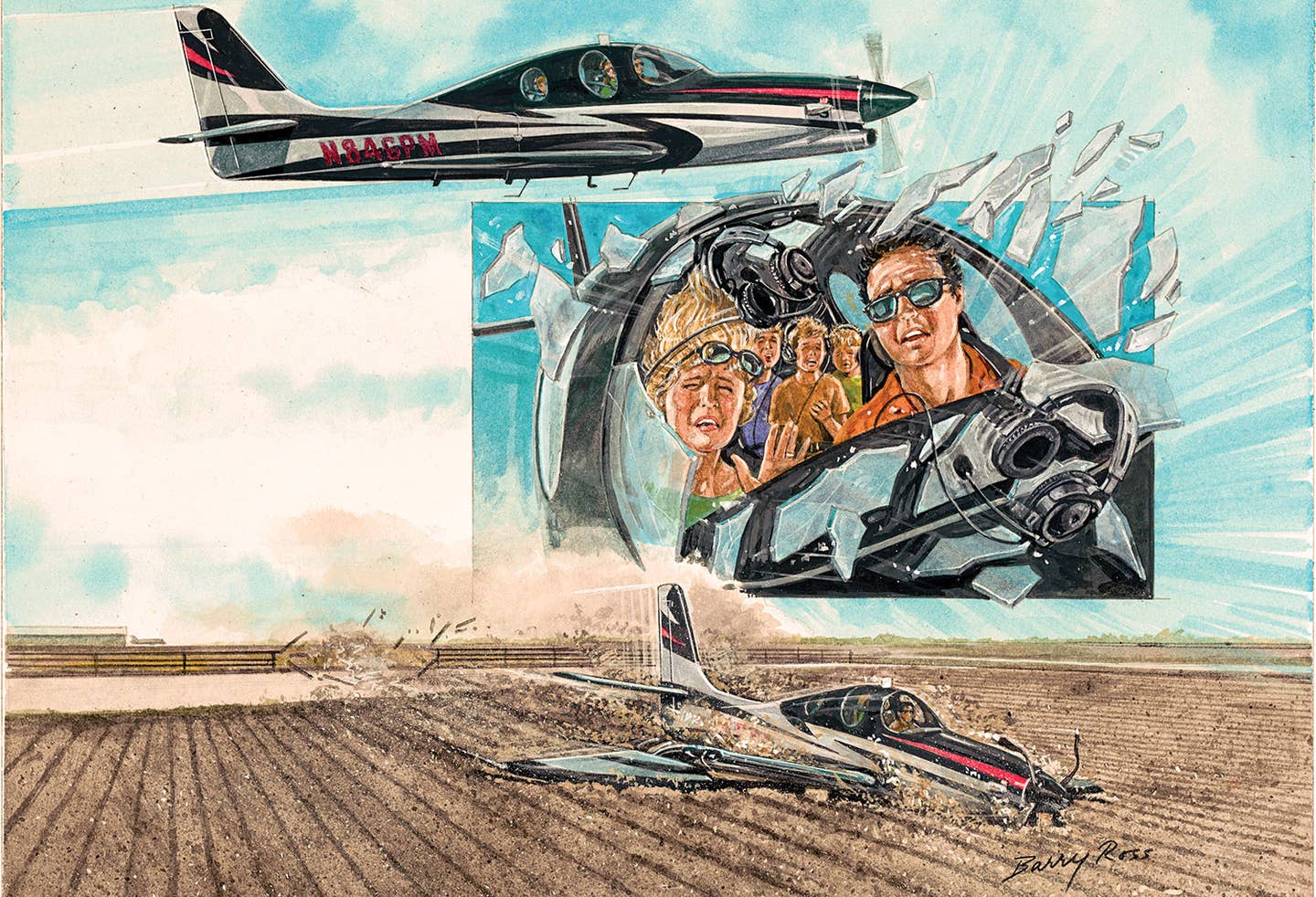

Inside 15 of the most terrifying minutes of one pilot’s life. Barry Ross/BarryRossArt.com

The gale-force winds that slammed into me when my windshield shattered instantly ripped off my headset, tore at the skin on my face and strained my ability to focus on anything beyond the immediate sensations assaulting me. One moment I was leveling off my Lancair Evolution at 25,000 feet. The next, I was in the middle of a maelstrom, the power of which few humans have ever experienced.

The noise alone was enough to rival a locomotive. And the cold. The temperature of the air at that height was around minus-15 degrees, and it was raging around my head, given my 310-knot airspeed. Fortunately, glass shards weren’t among the things flying around the cockpit. With a cabin pressure of 6.5 psi pushing against the Plexiglas, any pieces of that material blew outward.

Have you ever stuck your head out of a car window at 60 mph on a cold winter day? Now speed that car up by a factor of six. Oh, and drop the temperature to a point where it hurts to try to breathe. As pilots, we train incessantly for potentially catastrophic events. But during that training we’re typically in a relatively controlled environment and must deal with only one or two anomalous elements at a time. But outside of pilots who have served in combat, it’s hard for anyone to imagine the chaotic conditions into which I was instantaneously plunged.

My immediate thoughts were for my wife, sitting in the right seat, and my three sons in the back. I knew for certain that the only thing standing between them and an unthinkable outcome was my ability to put that airplane on the ground in one piece — and fast.

Miraculously — and I do mean that in the divine sense — my newly acquired sunglasses stayed on my head. I’d bought this particular pair because they were designed to be comfortable under a headset. Now, despite the wind and objects being thrown around the cabin, they stayed on my face when the headset blew off.

With the glasses on, I could still see. And, if I could see, I could fly. I’ve had my private pilot’s license since 2003 and have logged more than 1,100 flight hours — 120 of them in the Evolution. Training and instinct took over. As if losing the windshield wasn’t bad enough, the engine had stopped. I put the aircraft into a steep dive, gobbling up 5,000 to 8,000 feet per minute to get us down quickly.

Meanwhile, my wife, Jennifer, was twisted in her seat, helping the kids. There was no way she could talk to them because the wind noise was so loud that you could yell at the top of your lungs and a person inches away couldn’t hear a word you said.I activated the ancillary oxygen. My 12-year-old son, Jakob, got his mask on first. He assisted his two younger brothers, Lukas, 9, and Nickolas, 7. They struggled at first, but ultimately began buddy breathing. Terror clearly registered on their faces, but I was proud that they’d remembered what to do. I quickly got my mask on as well.

Saying a silent prayer of thanks for the sunglasses, I scanned the area, looking for a suitable landing spot. On our route from the San Francisco Bay area back to our home in Marana, Arizona, the visibility was over 10 miles, with scattered clouds. I had a grand vista of California’s San Joaquin Valley. Roads crisscrossed the landscape, but I discounted those due to traffic and power lines. And though there were plenty of open fields in the area, they were my last resort, for fear of flipping the airplane while trying to land on a rough surface.

I pushed a few buttons on my Garmin G900X avionics system and located a nearby airfield. It was a hard runway, 3,000 feet long. That would do. With no engine and no power, there was no second-guessing. I dialed in the heading and prayed.

As we neared what turned out to be Firebaugh Airport near Fresno, California, I tried to establish visual contact. Leveling off at 12,000 feet, I trimmed the Lancair and pegged the airspeed at 110 knots. I looked all around for the field while I continued my descent. Finally, at around 5,000 feet, I spotted the runway tucked between several roads and running parallel to a canal. Firebaugh is a nontowered field, so even if I hadn’t lost my headset or could hear anything over the roar of the wind, there was nobody to guide me on my approach.

I’d spotted the runway, but I couldn’t find the windsock to determine wind direction. I had to decide: Do I land on 12, or the other way on 30? I didn’t have the luxury of time to figure it out, but something guided me to come in from the northwest.

As I made my approach, I lowered the landing gear. Recalling that an actuator had been replaced during the plane’s annual inspection the prior week, I was disheartened to see the indicator light for the left gear remain negative. With just enough altitude and airspeed, I made a 360 to the left and tried again to kick out the gear. No luck. It stubbornly refused to lock in place.

OK, I thought, we’ll do this the hard way. Retracting the gear, I committed us to a belly landing — my first. I rechecked every instrument. I triple-checked every visual cue. I was oddly calm as all of my training kicked in. I progressed through my landing procedure.

On touchdown, I was amazed at how smooth it felt. Because of the retracted landing gear, I had come in faster than I would have liked. We skidded down the runway and overshot the other end. Breaking through a small fence, we crossed West Nees Avenue (thankfully empty of traffic) and came to rest in an empty field.

Only later did we find out how fortunate we were that I was guided to Runway 12. Had we come in from the other direction and skidded the same distance, we would have pitched into a steep irrigation canal with potentially disastrous results.

As it was, Jennifer sustained a cut on her shoulder (we suspect it was debris from the fence) which ended up requiring six stitches. Other than that, and some minor bumps and scratches, we were five for five — everyone was safe and sound. From the moment the windshield failed in such spectacular fashion to the moment we plowed to a stop, only 15 minutes had elapsed — 15 of the most terrifying minutes in my life.

In the aftermath of such an experience, it’s natural to wonder what I could have done differently. But the fact that I’m telling the story means I did quite a bit right. What did I learn? First and foremost, always take flying seriously. Even if you’re just flying for fun, you never know when a completely unexpected failure will plunge you into a life-or-death situation. Training and repetition help ensure that your reactions will be the right ones when you have to make split-second decisions.

The experience also reaffirmed the importance of knowing your aircraft and systems. Take recurring training whenever you can, and pay attention while you’re doing it. Don’t just go through the paces.

Finally, make sure you train your passengers as well. Knowing that my sons were breathing and that my wife knew how to handle herself in our situation allowed me to focus on getting the Evolution on the ground.

To this day, I have no idea what caused that windshield failure. The FAA is investigating the incident. According to the research I’ve done, nothing like this has ever been reported. But I am sure that, were it not for the fact that my Flying Eyes sunglasses stayed on my face, protecting my eyes and allowing me to see where I was going, and the divine guidance I received from a higher power, there might have been a much different outcome on that sunny afternoon.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox