Keeping Up in the 2nd Space Race Takes Diligence

How can NASA keep its ambitions for the moon and Mars on track?

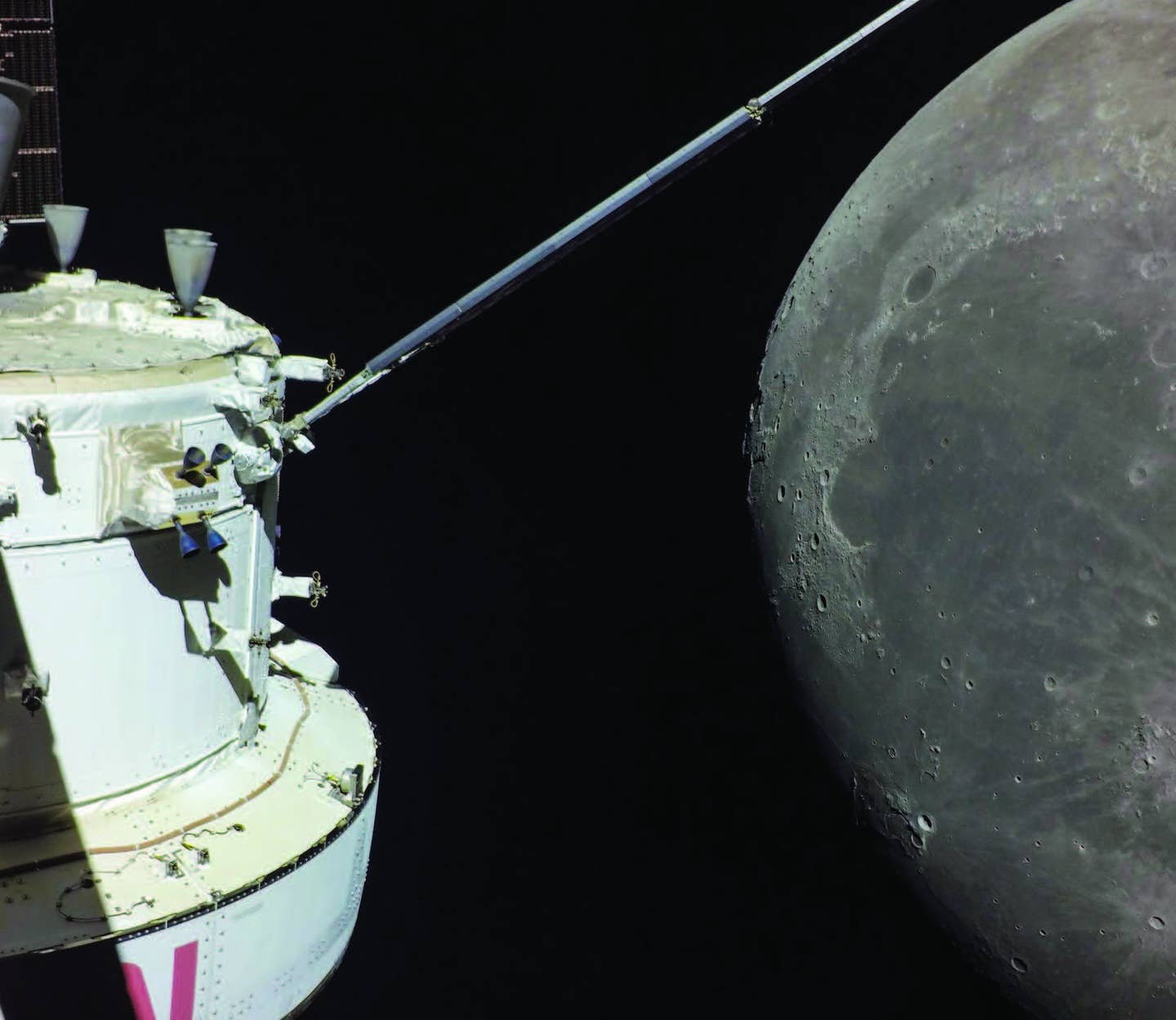

NASA’s Orion spacecraft passes within 80 miles of the moon during the Artemis I mission in 2022. [Courtesy: NASA]

The U.S. is in the midst of a second Space Race, and NASA is in a time crunch.

The space agency is preparing to send American astronauts to the moon for the first time since the Apollo era. But after delaying the Artemis III lunar landing twice in 2024, there is much work to be done. And experts believe NASA is on the clock.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe Now“The world finds itself in Moon Race 2.0, this time between the United States and China,” said Clayton Swope, senior fellow in the Defense and Security Department at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)—an influential space defense think tank on Capitol Hill. “But the United States already landed humans on the moon…The real race is to Mars, both for a human landing and also for a Mars sample return mission. No one has ever done either of those.”

According to Swope, NASA in the near-term can focus on returning rock and dust samples from Mars, where its Perseverance rover has been collecting them since 2021. But to actually land humans on the Red Planet, Artemis III is a critical stepping stone.

Why We’re Going

Artemis III will attempt to land NASA astronauts where no human has ever stepped foot: the lunar south pole. There, sunlight is so scarce that the valleys of some craters are permanently shrouded in darkness.

Scientists believe these shadowy regions could hold water ice, which might help researchers better understand the history of the solar system. It could even be repurposed to help astronauts live on the moon or gear up for missions to Mars and

beyond.

- READ MORE: SpaceX Stands Behind Its Ambitious Lunar Timeline

“You can extract oxygen and hydrogen from ice,” said Swope. “Strategically, it would be important to have access to these elements for fueling missions to Mars and other parts of the solar

system.”

If the goal is to use the moon as a base or waypoint for longer missions, the U.S. will need to get there first. Complicating matters is China, which plans to land an astronaut at the lunar south pole in 2030 and build a research base there.

“My personal view is that the United States should work to get astronauts to the moon again before China gets there for the first time,” said Swope.

Safety Versus Speed

Artemis III was pushed in January from September 2025 to 2026, then again in December from 2026 to mid-2027. Artemis II—a 10-day mission around the moon and back, originally scheduled for September—was also delayed to no earlier than April 2026.

The delays stem largely from a safety issue with NASA’s Orion capsule, which will fly the crew to space. Orion flew on the uncrewed Artemis I mission in 2022. But as the capsule reentered the atmosphere, pieces of charred material flew off its heat shield.

NASA did not know why until a few months ago. Officials said Orion’s outer layer is designed to wear away as it protects against temperatures approaching 15,000 degrees Fahrenheit. But trapped gases within the heat shield created cracks, causing large chunks to be ejected.

Engineers spent months investigating the root cause of the anomaly to ensure the safety of the crew. At the same time, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said modifying the heat shield for Artemis II could delay Artemis III even further to late 2028. So, rather than changing the material, NASA will instead change Orion’s approach to Earth to cap the buildup of gases within the heat shield. A fresh heat shield will be installed for Artemis III.

More Work to Be Done

NASA now has a plan for the Orion heat shield, though it is “taking longer than we thought,” an official said in December, to upgrade the capsule’s life support system.

Plenty more work must be done before Artemis II and Artemis III can fly, and not all of it is in the space agency’s control. Take, for example, contractor SpaceX, which must demonstrate key test objectives with its gargantuan Starship rocket and Super Heavy booster. A human landing system (HLS) variant of Starship will land the Artemis III astronauts on the moon.

- READ MORE: Here Comes That Hydrogen Power

SpaceX in 2024 pulled off an unprecedented booster catch, returning Super Heavy to the launchpad unscathed following a test flight. But NASA by the end of the year expects Starship to fly to the moon and back. Before then, it will need to transfer supercooled propellant between two Starships on orbit—another untested maneuver—among other milestones.

“We tend to discuss Starship succeeding as a fait accompli, and we have to remember that, for all the success that SpaceX has had, it’s pushing technological boundaries in a number of ways that have never happened before,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy for The Planetary Society. “There’s still a long way to go before it provides the capability that they intend to have.”

Under New Management

NASA and SpaceX have plenty of work to do. But in December the FAA authorized Starship for more test flights. That same month, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump tapped Shift4 CEO Jared Isaacman, a key SpaceX ally, as NASA chief to replace Nelson.

Per Dreier, the selection is unorthodox given Isaacman’s lack of government experience. But his passion for space is undeniable.

“He comes with this asterisk that he has been to space twice himself,” Dreier said. “These weren’t just passive tourist flights, up and down. These were very elaborate, risky, but well managed

efforts.”

Isaacman and his Polaris program purchased three missions from SpaceX, the third of which is intended to be Starship’s first crewed flight. Elon Musk, CEO of SpaceX, also appears to have Trump’s ear as presumptive cochair of the proposed Department of Government Efficiency. It’s unclear exactly how much sway Musk and Isaacman could have on the incoming administration.

But Musk was brought into the fold to cut government spending, and Isaacman has described NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS)—the launch vehicle for the Artemis campaign—as “outrageously expensive.” According to the NASA Inspector General, a single Artemis launch using the SLS would cost north of $4 billion.

Dreier said the probability of the SLS getting scrapped is “the highest it’s ever been…Does that make it likely? I don’t necessarily think we can say that.”

The challenge, he said, will be breaking up the “rock solid” congressional coalition that has repeatedly backed the SLS. A strong push to ax it could cost Isaacman confirmation votes from senators in Republican states, where much of the SLS workforce is located. But Isaacman is also a Democratic political donor, and his presentation as politically moderate could garner him support across the aisle.

Dreier also predicted Isaacman will bring a “commercial mindset” to NASA, which could help him navigate an increasingly tight budget environment.

“We’ve seen this already to an extent where NASA lost a couple of percentages on the top line—mixed up with inflation, you’re talking about a couple billion dollars of loss of buying power in the last few years,” he said.

Despite the limited allowance, Dreier expects the new management to make Artemis a priority. Outsourcing more work to private contractors could free up NASA to zero in on a few key mission elements.

From the standpoint of the second Space Race, Isaacman’s comments on Mars bode well, Dreier said. He found it notable that, following his nomination, Isaacman on social media emphasized landing on both the moon and Mars. NASA’s Moon to Mars initiative has yet to chart a course to the Red Planet. But perhaps that could change under Isaacman.

“I would caution against reading too much into that yet,” Dreier said. “But I think it tells you where the general tenor of the administration is going to be in terms of what topics naturally integrate to their philosophy.”

This column first appeared in the February Issue 955 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox