Meet Arkisys, the Startup Building the World’s First Private Spaceport

The company’s Port ecosystem should ramp up space activity by providing a hub for just about everything.

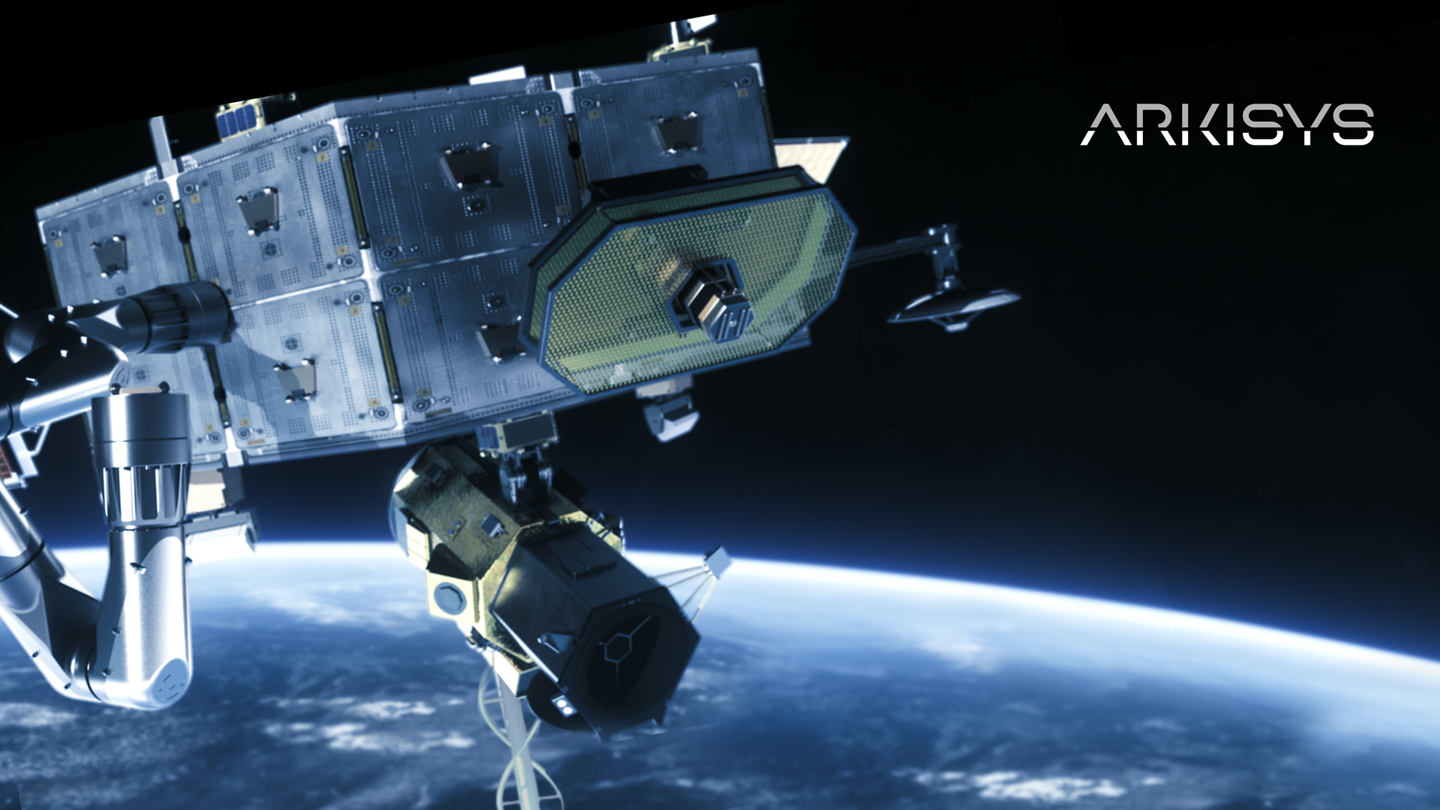

A digitalization of an individual Port module loaded with different equipment. [Courtesy: Arkisys]

By some accounts, ports have been around for millenia, with the oldest believed to be Byblos Port in Lebanon, established some 5,000 years ago. Those ports look nothing like today’s—but they served a similar purpose.

“Fiefdoms come and go, kingdoms come and go. But the port itself and the location has arisen as a way in which humans collaborate and onboard and offboard commodities that get shipped around the world,” Dan Lopez, chief business officer of spaceport startup Arkisys, told FLYING.

Arkisys borrows the name of its flagship product, the Port, from earthbound maritime logistics hubs, aiming to accomplish what they have done for the planet—connect people, transfer capital, and scale up businesses.

Lopez describes the Port as the first space outpost providing assembly, integration, and resupply for private companies and startups. And his vision for its applications is as grandiose as it gets: It could one day ferry payloads to the International Space Station (ISS), refuel passing spacecraft, construct satellites in orbit, or even facilitate communications between Earth and Mars.

In short, Lopez envisions the Port as a ubiquitous, platform-agnostic hub to enable rapidly deployed space operations for companies that would never have a chance to do so. But let’s break down how Arkisys plans to do all of this.

What’s the Port?

There are a few different components to the Port architecture, each serving a unique purpose.

The Port module itself consists of one or more hexagonal spacecraft, with six detachable sides measuring about 6.5 feet high by 3.25 feet wide. Each module is constructed from steel and 3D printed elements and provides structural, thermal, electrical and data interoperability between each other and the Port’s other components, looping everything into one system.

Each side of the module is called a Cutter, which also has a maritime counterpart. Arkisys will use Cutters to ferry other companies’ payloads to and from the Port—a native integration between the two allows them to rendezvous. Importantly, those payloads could come from any number of firms, since the system is designed to be platform and vessel agnostic.

“Current orbital transport vehicles (OTVs) charge half the amount it costs to launch your payload anyway,” Lopez said. “So we thought through it, and we would be negligent in our business modeling to think that it would be OK to do that. We want other OTVs to come to the port.”

The Port and Cutter modules each fit inside larger launch vehicles. For example, Lopez said, launch systems company ABL Space Systems could send both into orbit, where the spacecraft could then guide itself into position.

To allow different payloads to attach to the Port, each of its six sides features an interface called an applique, which Lopez described as “akin to a USB in space.” The patent-pending technology inducts mechanical systems, electronics, and external protocols for data into the Port’s own systems.

“Imagine your laptop,” Lopez said. “Apple doesn't care what you plug into it—if it plugs into a USB-C, or an adapter that translates USB-C to USB-3, maybe you have an older MIDI keyboard…That’s the exact same kind of idea, but nothing like that exists for space.”

Docking a small spacecraft, satellite, or other payload to the Port requires the precision of a neurosurgeon. So Arkisys gave it “hands” in the form of a robotic arm that can move, manipulate, and grab objects from approaching vessels. According to Lopez, the arm “essentially has a toolshed” of attachments that it can use to perform its tasks.

The final component of the Port ecosystem is the Boson’s Locker, which is essentially a shipping container for space. Each Locker has interfaces that allow it to connect to the Port and the Cutter, or be stacked on another Locker.

The Do-It-All Spacecraft

Lopez views the Port as a breeding ground for innovation but not for Arkisys. He compared it to Amazon Web Services—a product built to, well, build products.

Each Port module will be able to perform multiple functions at once. Satellite servicing and repairs, refueling of passing spacecraft, and payload delivery between Earth and orbit are a few potential use cases. Rapid prototyping, testing, and development of new space technology is another the company promises to enable early on, and mining, resource utilization, and long-distance space communications may come in the future.

But the applications get far more whimsical.

Not only is the Port expected to repair satellites—it will be able to serve as one. Arkisys can aggregate Cutters carrying radar or communications equipment to create a free-flying spacecraft, or what Lopez refers to as a “common bus.” So, in theory, an Arkisys customer could use the Cutters (or an entire Port module) as a satellite base, attaching equipment for whatever use cases they need.

Perhaps even more exciting is that Arkisys is looking to build satellites from the Port—while in orbit—as well.

It plans to do so through two interfaces, the first of which is hardwired to the Port’s robotic arm. Lopez couldn’t get into the finer details, but he explained the configuration solves certain physics problems and allows the arm to move, attach to an interface, detach, and reattach somewhere else.

The arm’s claw, or end effector, will be able to grab materials, bolt into interfaces, and translate data, electronics, and mechanical commands and controls through them.

Arkisys will also deploy something called a HighSat, which Lopez said is akin to a CubeSat but half the size. These small satellites, each equipped with electronics and propulsion, work with a different interface that allows them to interlock with each other and create a single system. And since they can also bolt onto the Locker, Arkisys can use its arm to build new payloads—like remote sensing cameras or solar panels—and integrate them to the HighSat body.

When construction is complete, the Port acts like a launcher, ferrying the new satellite to a different location or shooting it out into an orbital plane. The collection of HighSats and equipment can also attach to a Cutter, allowing it to travel farther, faster.

Essentially, a customer could send Arkisys the materials to build a satellite, and the company would beam them to space, build it, and launch it for them.

Lopez said payloads such as remote sensing cameras—which are designed to be reusable and stay in orbit for long periods—are the most ideal fit for this application, since the Port can refurbish and relaunch them.

“We have too much stuff in space,” he said. “We're not reusing it, and we're programming stuff to come back to Earth and burn up. And that is just essentially deforesting our precious commodity of orbits around the Earth orbital class. So what we propose is a stable, long-duration platform.”

Arkisys can also time those launches with agility and precision, quickly sending out a satellite to snap a photo. Or, if a customer wanted to take pictures of a specific location, it could calculate the orbital plane that passes by it most frequently.

While all of this sounds a little out-of-this-world, the company recently signed a deal with the U.S. Space Force to test out its satellite-building capabilities. The project is expected to ramp up next year.

How the Port Could Change the Game

There are two key advantages the Port provides: accessibility and cost.

To that first point, a growing number of space startups are looking for ways to test and validate their ideas in space. But doing so on a hosted payload, like another company’s satellite, can restrict launch timing and duration. And testing new technology on government-owned spacecraft, like the International Space Station, has limitations resulting from the presence of humans.

“If you go up to the ISS, which [involves] an extraordinarily high amount of red tape, to test out your idea, your technology, there's a whole bunch of other things you can and cannot do,” Lopez said.

The Port, conversely, is designed to open up new applications. Lopez listed a few potential ones: nuclear, radio and energy, microwave, and infectious disease research. He added that space travel and exploration is tightly tied to government-sponsored programs—from which Arkisys wants to move away.

“You can't go and turn on a synthetic aperture radar or microwave antenna outside the ISS because you'll fry the brains of cosmonauts,” said Lopez jokingly.

The other key benefit is cost. Arkisys is tight-lipped about end-to-end pricing, but its goal is to reduce the cost of launches—which is typically tens of millions of dollars—exponentially.

“We'll take your payload or your spacecraft or whatever it is, reduce the time for integration, reduce risk, reduce costs, and then off you go,” Lopez said.

For now, interested startups can pay $5,000 to receive a ground-based version of the Port’s applique interface and integrate with Arkisys’ digital twinning program, which more than half a dozen companies have already done. The software models how a customer’s hardware would get to space and how it would behave while there, allowing them to test new scenarios—and when the time comes, integrate seamlessly with the Port.

“That's like going to AWS [Amazon Web Services] and trying something out for five bucks,” Lopez said.

Path to Launch

Arkisys is developing its components at two facilities near Los Angeles and has conducted electronic, thermal, and propulsion testing on the ground.

The company has also built a ground unit with the subsystems needed to control a prototype robotic arm that can manipulate payloads. A few applique modules have also been completed—Lopez said the first has been delivered to a launch provider and is ready to go.

The applique is expected to launch soon, followed by the first Cutter in 2024 and an entire Port module by 2025 or 2026. Next year, Arkisys plans to launch select companies' payloads for just $150,000 through a program called Embark U.S., sponsored by the federal government.

One of the company’s most ardent supporters has been the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), an organization within the Department of Defense focused on scaling and speeding the adoption of commercial technologies.

Through the DIU, Arkisys obtained an other transaction authority (OTA) contract that allows other agencies to quickly join their contract, especially if they have funding. According to Lopez, several research labs within the military have shown interest in launching their technologies with the company.

That interest has extended to other governments as well—for example, Arkisys is working closely with the government of New Zealand and its Ministry of Business, Education and Employment, which oversees the country’s space agency. So far, it has assisted with debris mitigation and strategies for docking in space, and the country will eventually use the Port to support more innovation.

The main thing holding back Arkisys—and the rest of the industry—is funding, Lopez said. That will most likely come from the government, which heavily backed SpaceX’s rise to stardom.

“A massive challenge is having governmental entities understand that it takes a village,” he said. “And we have to work with all of the moving parts: NASA, NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration], Congress, everyone, to understand how to ramp up innovation. Otherwise, the U.S. will be struck by lightning from external forces.”

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox