NASA Partners Are Developing a Post-ISS Space Ecosystem

Space agency provides updates on nine of its commercial partners developing the destinations and technology that will maintain a human presence on orbit beyond this decade.

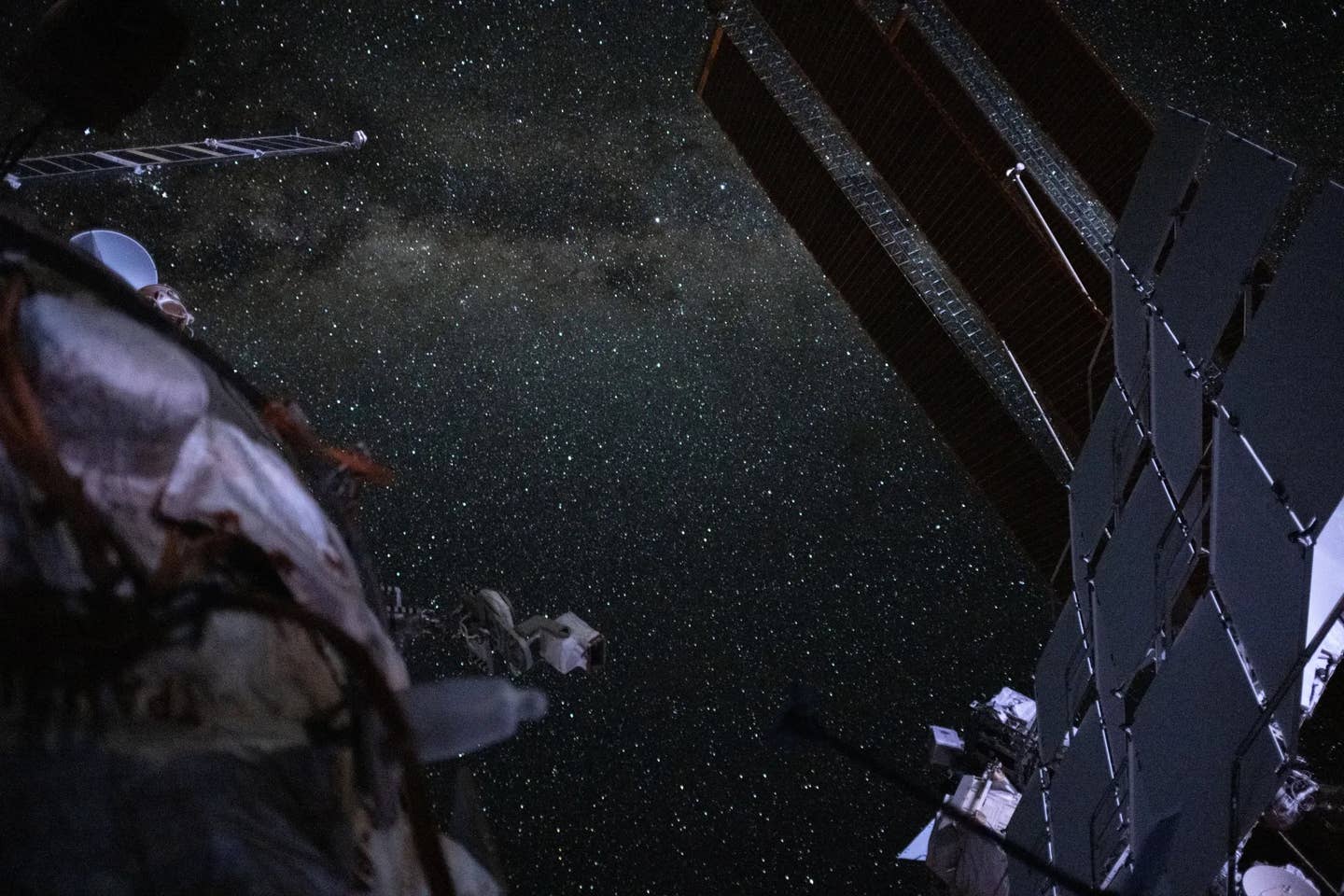

The International Space Station (ISS) is the lone U.S. commercial space station orbiting the Earth—but by the end of the decade, low-Earth orbit will be more crowded. [Courtesy: NASA]

At the end of the decade, NASA and SpaceX will destroy the International Space Station (ISS) and bring the pieces crashing back to Earth. But the space agency has a plan to maintain a human presence in low-Earth orbit (LEO) beyond the orbital laboratory’s retirement.

NASA this week provided updates on nine of its commercial partners, which are developing technology from microgravity space stations to the vehicles that will build, service, and fly to them. Some of these NASA-backed systems could launch as early as next year, while others will deploy toward the end of the decade.

Seven firms are partnered with NASA under the Commercial Space Capabilities-2 (CCSC-2) initiative, which grants unfunded Space Act Agreements offering NASA expertise in lieu of cash.

Blue Origin and Sierra Space, for example, are developing the Orbital Reef commercial space station, expected to be operational by 2027. Sierra is building Orbital Reef’s Large Integrated Flexible Environment (LIFE)—a space habitat that stows away on a rocket and inflates on orbit—as well as the Dream Chaser spaceplane that will deliver crew and cargo.

NASA on Monday said Sierra completed two full-scale “burst tests” of the LIFE habitat, filling it with air until the structure literally burst. The company also selected materials for LIFE’s air barrier and has made progress on impact testing and thermal systems, among other things. Blue Origin, meanwhile, “continues to make progress” on a system NASA says will provide safe, affordable, and routine transportation in U.S. orbit.

SpaceX, NASA’s largest contractor, is building infrastructure for LEO that could open up missions to the moon, Mars, and beyond. Variants of its gargantuan Starship rocket will serve as orbital waypoints and vessels to land humans on distant moons and planets, supported by the company’s Falcon Heavy booster, Dragon capsule, and Starlink satellites.

SpaceX this year completed four test flights of the reusable rocket and booster, demonstrating landing and deorbit burns. It even caught Super Heavy back on the pad from which it launched using a pair of robotic arms—an unprecedented maneuver that helped validate the ability to quickly refurbish the booster for future missions.

The company is gearing up to launch new, more powerful generations of Starship next year. It could attempt to catch the rocket itself and perform an on-orbit transfer of supercooled liquid oxygen and methane propellant—also unprecedented—in early 2025. By year’s end, NASA anticipates the launch of an uncrewed Starship to the moon ahead of the Artemis III lunar landing.

Northrop Grumman, another major contractor, recently finished a NASA program management review of its Persistent Platform—a variant of its Cygnus spacecraft designed for autonomous commercial logistics, research, and manufacturing capabilities on orbit.

The company is also making progress on Persistent Platform’s docking capability through a partnership with Starlab Space, a joint venture between Voyager Space and Airbus. That firm is building a second commercial space station called Starlab that will launch no earlier than 2028.

Vast is developing yet another commercial space station called Haven-1, which will launch to orbit no earlier than August. According to NASA, the firm has already built several Haven-1 components, including the hatch and battery module, and conducted solar array and pressure testing.

CCSC-2 partners Special Aerospace Services (SAS) and ThinkOrbital are tackling what may be an even bigger challenge: space stations that can build other space stations on orbit. Both companies are getting closer to showing what they can do—particularly ThinkOrbital, which demonstrated orbital welding for NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) earlier this year and will do so twice more in the coming months.

Two more commercial firms are working with NASA under Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contracts as part of a pilot program called SBIR Ignite, funded by the space agency’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

Canopy Aerospace, which according to NASA recently wrapped up materials testing, is developing a manufacturing system that could improve production of the heat shields that protect spacecraft from extreme hot and cold temperatures. Thermal protection systems (TPS) in use today date back to the Space Shuttle era, but Canopy intends to improve them with updated materials.

The other SBIR contractor, Outpost Technologies, just conducted an 82,000-foot drop test of its Cargo Ferry prototype: a reusable spacecraft designed to more frequently fly science and hardware from commercial space stations back to Earth. The vehicle will be powered by solar panel-coated wings and deploy a robotic paraglider for soft landings.

During the test, the paraglider deployed at 65,000 feet up—a record for such a system, NASA says. The glider autonomously guided the Cargo Ferry about 165 miles to a precise landing, demonstrating the design’s reusability, range, and recovery capabilities.

These commercial outposts and technologies will one day dominate the LEO ecosystem—and NASA, which relies on an LEO presence for science, has a vested interest in their success. Expect the space agency to continue monitoring the progress of its commercial partners and turn to them for additional work as it transitions to a new era of orbital activity.

Like this story? We think you'll also like the Future of FLYING newsletter sent every Thursday afternoon. Sign up now.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox