NASA Picks SpaceX to Deorbit the ISS

The space agency is enlisting the private firm to build an International Space Station vehicle that will ‘destructively break up’ along with the station when it is retired in 2030.

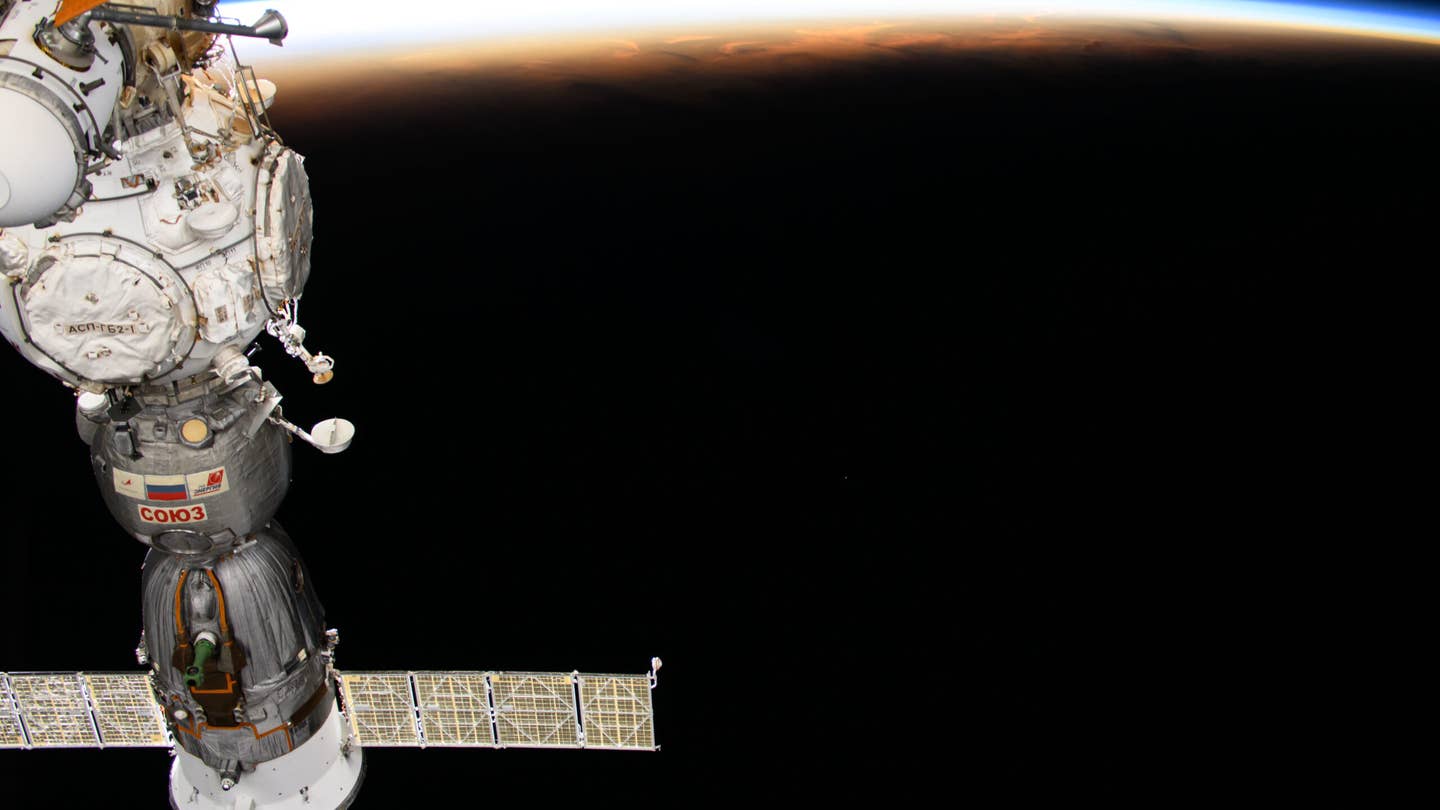

After 2030, the International Space Station will be replaced by a collection of commercial space stations built by private companies. [Courtesy: NASA]

In its latest collaboration with private industry, NASA has selected the company that will bring the International Space Station (ISS) back to Earth in pieces.

The space agency on Thursday announced it awarded SpaceX a contract, worth up to $843 million, to build a vehicle that will deorbit the space station when it is retired in 2030. At the end of the laboratory’s lifespan, NASA will use the SpaceX-built vehicle to bring it crashing down into a remote section of the Pacific Ocean.

The Biden administration in 2021 committed to extend ISS operations through the end of the decade. After that, it is planned to be replaced by an array of NASA-funded commercial space stations.

“Selecting a U.S. Deorbit Vehicle for the International Space Station will help NASA and its international partners ensure a safe and responsible transition in low Earth orbit at the end of station operations,” said Ken Bowersox, associate administrator of NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate. “This decision also supports NASA’s plans for future commercial destinations and allows for the continued use of space near Earth.”

Once the vehicle is developed, NASA will take over and oversee its operation. Like the ISS, it is expected to break up as it throttles toward the Earth. A launch service will be procured in the future—the agency currently uses SpaceX’s Falcon rocket to launch Commercial Crew rotation missions to the orbital laboratory.

Deorbiting the ISS will be the responsibility of the U.S., Canada, Japan, Russia, and member countries of the European Space Agency (ESA). Since 1998, the ESA, NASA, Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Russia’s Roscosmos have operated the space station, occupying it continuously for almost a quarter of a century.

In that time, it has been used to conduct microgravity experiments, test technologies that could be used to explore the moon and Mars, and, more recently, host commercial activities such as private astronaut missions.

According to an FAQ on NASA’s website, the agency expects itself to eventually become one of several customers, rather than a provider, of those services in a commercial space marketplace. As private companies take over low-Earth orbit operations, it will focus on flying humans to the moon, Mars, and beyond.

The first crewed lunar landing in the Artemis moon program, for example, is scheduled for September 2026. SpaceX is involved in that effort, too, developing the landing system that will put astronauts on the moon’s south pole.

NASA weighed several options for decommissioning the ISS, including a disassembly in space or boost to higher orbit, before settling on a controlled reentry. It will lower the station’s altitude using onboard propulsion before deploying SpaceX’s specially designed deorbit vehicle to bring it back into the atmosphere.

After lining up the debris footprint over an uninhabited area of the ocean, the space agency will give the all clear for one final burn. Most of the laboratory is expected to melt, burn up, or vaporize.

NASA in 2021 selected three private companies—Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, and Starlab Space, a joint venture between Voyager Space and Airbus—to develop free-flying commercial alternatives to the space station. The firms were awarded space act agreements totaling $415 million.

Another private partner, Axiom Space, is designing four modules that will attach to the ISS and later jettison to form another commercial space lab. The company is in the design review phase and is on schedule to launch its first module in 2026 under a contract worth up to $140 million.

All four spacecraft are expected to be operational before the end of the decade to ensure a smooth transition away from ISS operations, but NASA will first need to certify them.

Like this story? We think you'll also like the Future of FLYING newsletter sent every Thursday afternoon. Sign up now.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox