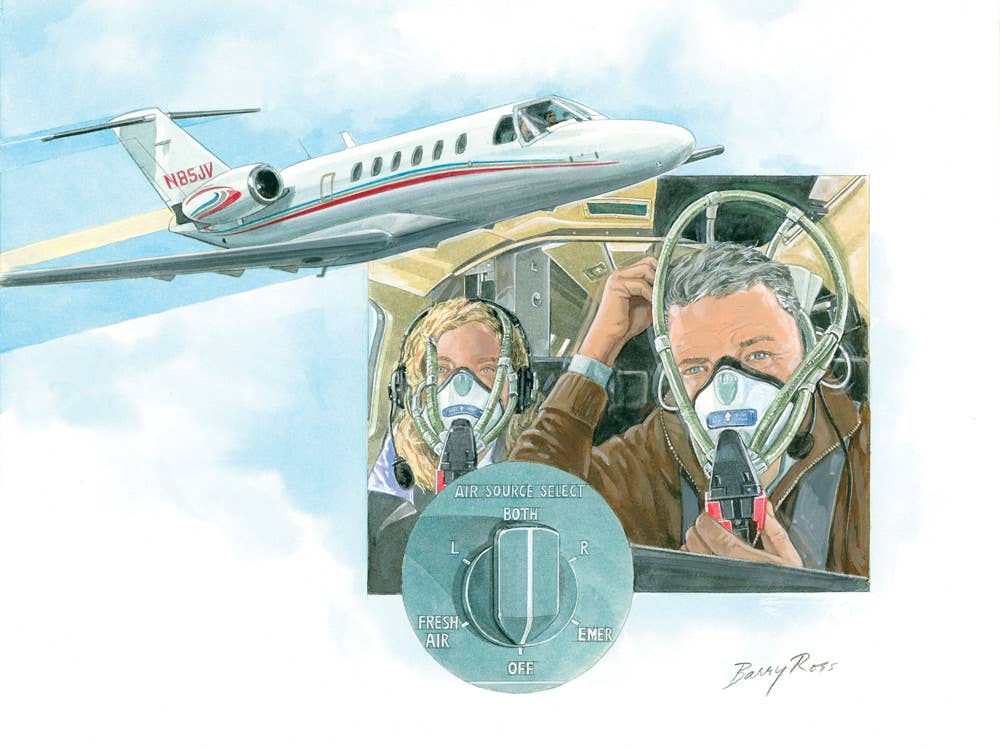

A return from maintenance, and an inflight gotcha waiting to happen Barry Ross

The chattering of alarms in the cockpit grabbed my attention. The Cessna CJ2 had just blasted through 12,000 feet, and now 14,000 feet, after takeoff from John Wayne Airport in Orange County, California, for our short flight to San Luis Obispo. I checked the annunciator panel and noticed the Cabin Alt red light was illuminated. I also looked at the pressurization gauge and noticed it was above 10,000 feet. I actually started to feel the altitude change myself, so I quickly donned my oxygen mask and told my 12-year-old daughter in the copilot seat to do the same. My wife, who was sitting in the rear seat, copilot side, saw me do this and started to grow concerned — well, she freaked out, really. My 17-year-old daughter was in the rear-facing, pilot-side seat and didn’t seem fazed at all.

The week before, we had the Holy Fire burning out of control in Southern California, and returning from a business trip to Arizona we flew through a 3,000-foot-thick layer of smoke and ash before landing at John Wayne Airport. I called my maintenance provider and asked about the benefits of an engine wash to make sure any residue was cleaned out. They agreed it would be beneficial and picked up the airplane to perform the service.

When I went to fly, knowing that the service was performed, I did an extra-long preflight throughout the exterior. I made sure the oil was above the fill line, stood back from the airplane to be sure no control surfaces had any signs of impact, checked under the wings, made certain all doors for cargo, front and back were secured.

Not much different than a normal preflight, but I did take about twice as long to give everything a good, thorough look. I knew they dry-motored the engines but didn’t add fuel. They never actually started the engines, just turned them using the power of a GPU cart.

As I loaded my family into the airplane, I pulled out my checklist and began to do my interior preflight. I’ve got it down pretty well as I fly once or twice a week and have about 200 hours in this airplane since the beginning of the year.

I do, however, use the checklist to check my work and make sure I didn’t forget anything.

All items were good so we started up and taxied for takeoff. During climbout from John Wayne Airport, we were cleared from 9,000 to 16,000 feet on our way out toward Catalina Island for a northerly turn along the Los Angeles shoreline. Once we blew through 12,000 and 14,000 on our way up, the alarms sounded.

After donning the mask, I dialed a descent to 8,000 feet into the autopilot, pulled the power back to allow a quick descent and set the vertical speed to 3,000 feet per minute to get us down quickly. I then called ATC to let them know we had a pressurization problem and needed to descend. They approved the descent to 8,000 and asked if I needed to declare an emergency. I told them not at this time, that I was diagnosing the problem and asked if we could remain on the same heading, knowing that I was nearly to LAX and that would be a great place to land if I did need to declare, no matter which direction the wind was coming from, given the super-long runways.

I pulled out my emergency checklist and began to go through it. One of the items was to try a different air source. In a jet, the air-source controller generally takes bleed air from both engines to pressurize the plane.

If one of them has a leak, or isn’t working for some reason, you can switch the controller to Left or Right. You can also turn it off, but you would never do that because then the airplane wouldn’t pressurize.

Well, after looking at the controller, guess where it was set? Off! Since the day I’ve owned the Citation, it has never been set to Off.

I quickly found the reason for my pressurization problem — no bleed air pressurizing the cabin. I set the controller to Both and immediately saw the airplane begin to pressurize at 500 feet per minute, and the cabin altitude descend. Thinking that we could handle more, I set it to manual and set the cabin descent to 1,000 feet per minute. Well, everyone felt that maneuver in their ears and complained, so I switched back to auto and just let it do its job.

In about five minutes, everyone was feeling better, and in 10 minutes the cabin was down to 5,000 feet. I then asked the controller for a climb to 14,000 to make sure everything was working, and the cabin didn’t climb anymore, so all was good.

Read More: Rocky Mountain Low

The moral of the story is this: A thorough preflight when exterior work is performed is a must, but so is a thorough interior preflight. The shop apologized for the controller being left in the Off position. They said they needed to do that to make sure no water got into the lines when they performed the engine wash. I’ve had that done before, but I guess the other shops had remembered to turn the controller back to Both when they were finished. I will also use my interior preflight checklist, line by line, after a return from service and be sure not to skim it.

You’ve heard the admonitions in the past I’m sure — if there’s been maintenance done, be extra thorough in your preflight. Well, I’ve been flying for 30 years and owned my own aircraft for the past 12 years, so I’ve exhibited that extra diligence on many occasions, except for this one!

I gained some experience on this flight. I’m sure I’ll make other mistakes, but I feel pretty certain I won’t make this one again.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox