Recalling Glenn Curtiss on a Flight into Albany International

The aviation pioneer made a famous journey from a nearby farm field in 1910.

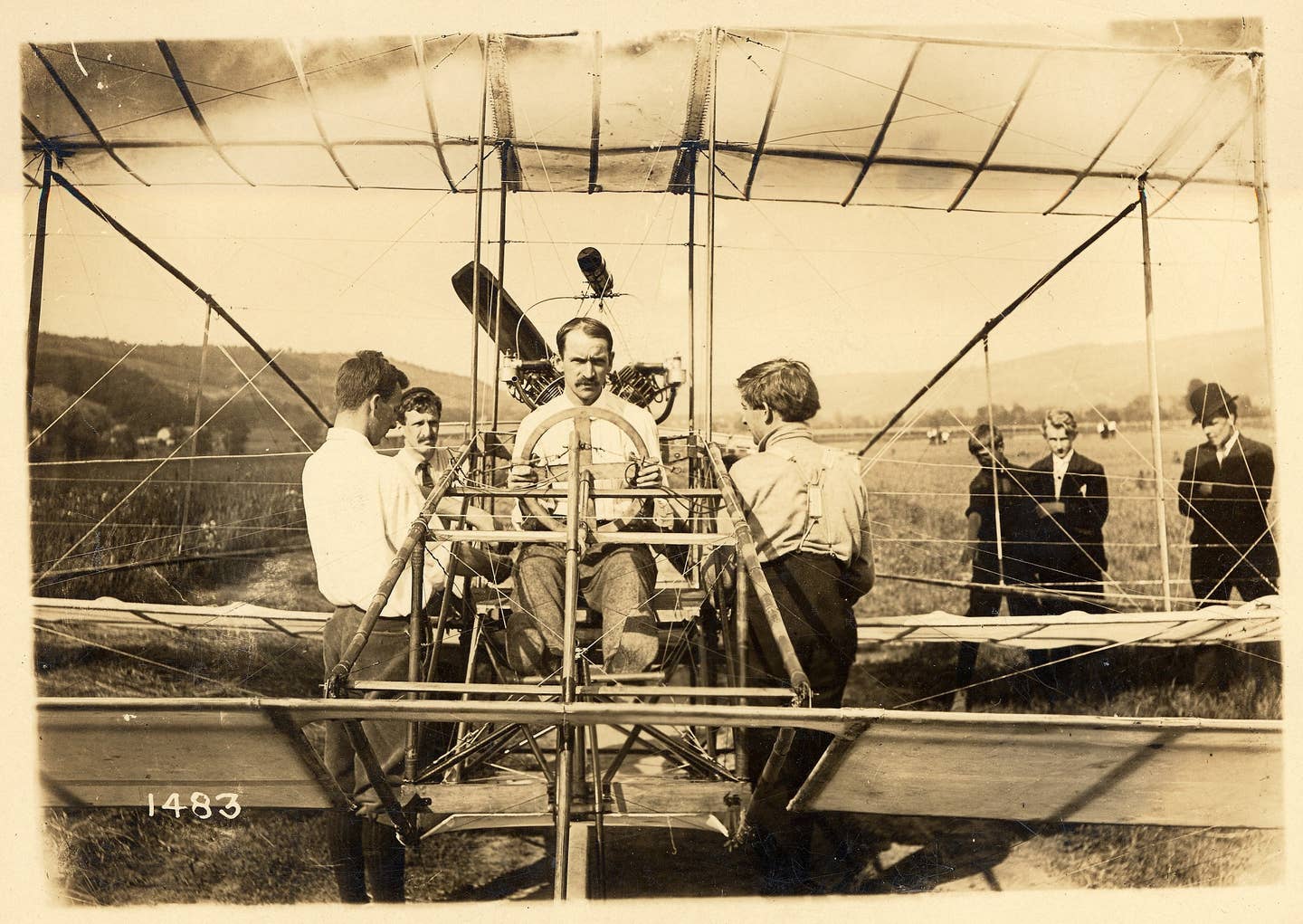

Glenn Curtiss was famous for aviation exploits including a record-setting flight from Albany, New York, to Manhattan in 1910. [Courtesy: National Air and Space Museum]

As I looked down at the scenic Hudson River Valley during a flight to Albany, New York, (KALB) this week, I thought about aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss, who made a similar trip more than 110 years ago.

Curtiss flew lower and slower, kept an eye on chimney smoke to help in reading the wind, and made two pit stops on the way. In my case the Garmin G5 in my Commander 114B’s panel displayed a small arrow indicating wind direction and speed. I didn’t need to follow the river closely because I could track the magenta line on the GPS screen. In truth, I left that to the autopilot for much of the flight. This might have offended Curtiss. In his day flying was a physically demanding challenge.

At 5,500 feet I felt relaxed as I tweaked power settings, adjusted the cabin air vents, and took in the scenery. After clearing the hills about 30 miles south of Albany, I descended to 3,500 and called Approach. I was making a round trip from Sussex Airport (KFWN) in New Jersey as part of a long-term study of our vast airport network, including Albany’s fascinating history.

Traffic was moderate, so I received several vectors before reaching a left base for Runway 19, switching to the tower and being cleared to land. “Number two behind the 757 on a right base,” the controller said, with a note to be mindful of wake turbulence. That was my first time following an airliner to the runway. I think Curtiss would have been impressed by that experience but still would have considered me a bit too sheltered in the Commander’s comfortable cockpit.

For the 1910 flight, he sat on a plank-like seat of his Curtiss Pusher in the open air. He wore fishing waders, leather jacket, and hat for warmth, goggles for protection, and flotation gear in case he had to ditch in the Hudson. The airplane had emergency floats as well. It might have seemed as if he was flying across an ocean instead of down a river.

But consider the era. It was May 29, 1910, when Curtiss took off from a farm field on the outskirts of Albany for a flight to Manhattan. Aviation was in its infancy. Curtiss and other pilots typically flew their machines around fairgrounds or parade fields, where a lap or

two would impress audiences. But the distance of about 130 nm to Manhattan was considered so far that the New York World newspaper offered $10,000 to the first pilot to complete the one-way trip. Curtiss got to choose which direction he would fly and decided on traveling southbound due to favorable winds, according to the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, New York.

After about two and a half hours, Curtiss arrived in New York City to claim his prize. There were still decent landing fields available in the area back then, and no Class B airspace limiting a pilot’s options. Curtiss easily set a distance record and took credit for the first true cross-country, point-to-point flight in the U.S. The feat also changed the outlook for aviation, confirming its potential as transportation, not simply entertainment.

Years earlier I covered some of the same territory as a student during my long cross-country solo. Flying the middle leg between Columbia County Airport (1B1), just south of Albany, and Orange County Airport (KMGJ) in a Cessna 172M with a sectional on my lap (no GPS), I realized I could follow the Hudson south for at least 30 nm before having to turn west toward Orange. This was a revelation at the time.

The route I took was longer but more interesting than the direct version. It was February, the river was frozen, and I could see icebreakers at work, fighting to keep the shipping lanes open. This diversion was precious. It gave me a better feel for the airplane, the local landscape, and my navigational capabilities. I was not ready to cross an ocean yet but was confident I could still find Orange County on my new course.

For Curtiss, the river was the most reliable guide into the city. Today we can use GPS, VOR, and detailed charts. We can also follow interstate highways or simply aim for the prominent skyline. These resources were not available to Curtiss. Aviation has come a long way.

So has the Albany Airport. From farm and polo fields that early pilots used to the 1928 version with multiple turf runways to today’s international facility, the place has long been a hub of aviation activity and continues to be an inviting destination for general aviation. Million Air, the FBO, is a great spot for meetings or to pick up a rental car. There are crew cars for shorter trips into town.

The tower was sympathetic as well. As I taxied to the FBO, I heard a controller tell a Southwest 737 that was about to turn from a parallel taxiway to “make way for the Commander on your right.”

It felt like they had been looking forward to my arrival.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox