Revisiting a Dream

For a new pilot, a flight lesson can be an exercise in building confidence in the aircraft, a new instructor and—perhaps most importantly— themselves.

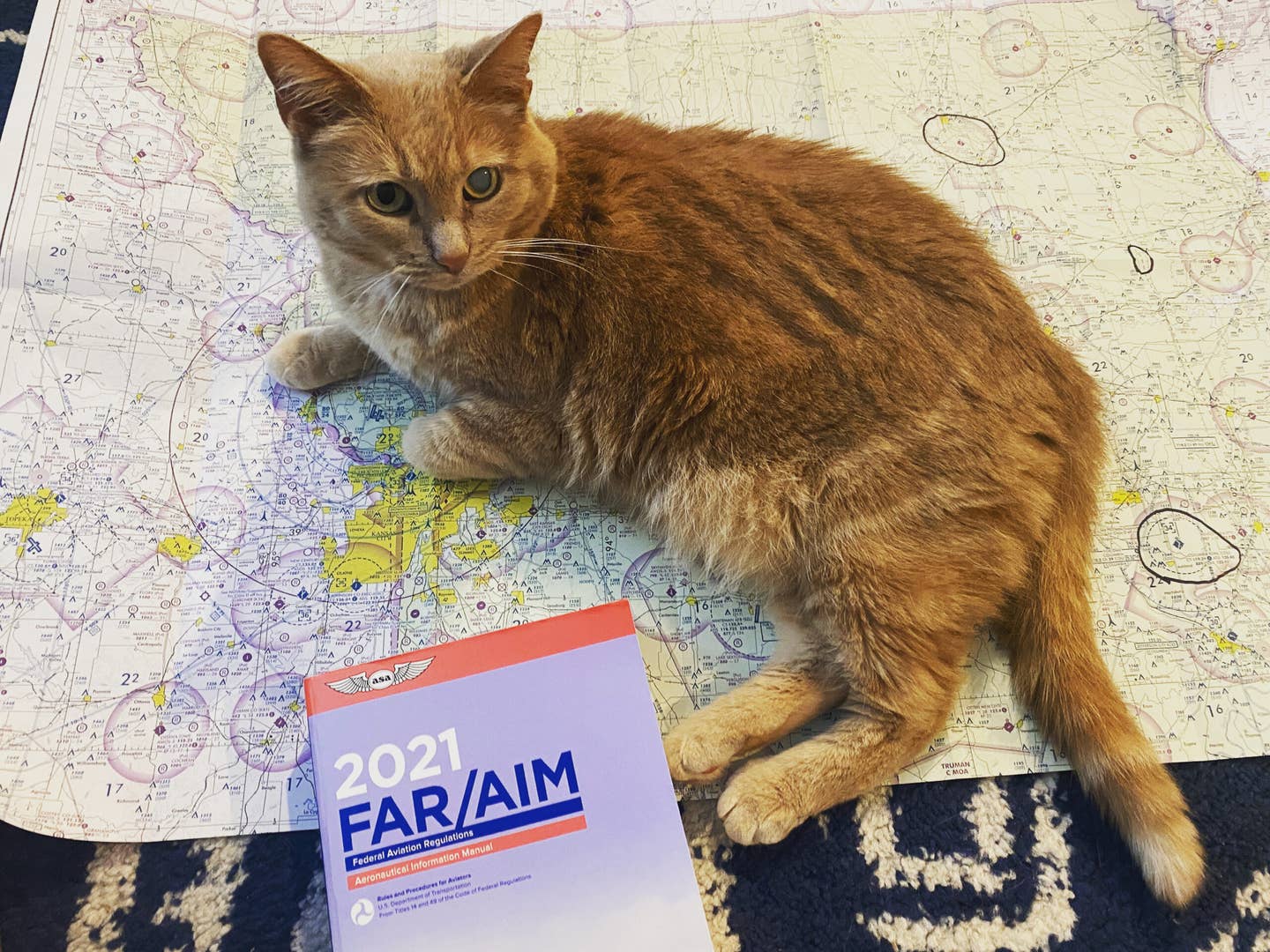

[Courtesy: Amy Wilder]

The wind whipped my hair sideways as I walked across the ramp to meet my instructor for the first time nearly a year ago when I started my private pilot journey. Or rather, resumed my journey. I took my first lesson at 14 and have been obsessed with airplanes from age 11 or so, when my sister and brother-in-law took me up for my first ride in their Cessna 172 to view the historic Missouri River flooding in 1993. I was hooked.

My bedroom walls were plastered with vintage airplanes and Hubble images by the time I was in high school. I subscribed to Astronomy and FLYING and devoured every science class my rural school could offer, graduating a year early, starry-eyed and dreaming I’d one day be the first person on Mars.

I can hear you laughing. But the spirit of that absurdly naive, intrepid 17-year-old has propelled me through an interesting, difficult, beautiful life so far, and she is still cooking up wild adventures. And while I have no plans—or desire, any longer—to leave the planet entirely, I will never quite get my head out of the clouds.

After a four-hour chat with a Navy recruiter who wouldn’t tell me I could be a pilot (I can hear you laughing again) but wanted to put me in the nuclear sub program in Maryland after I scored 98 on the ASVAB, I walked out and enrolled at the University of Central Missouri (Central Missouri State University, then). I chose the school for its overall affordability, study abroad opportunities, and aviation program.

I worked my way through college, and I couldn’t afford the flight training hours on top of tuition, so I reluctantly set aside my dream of flying until I could either go to Officer’s Training School or afford to fly on my own.

Turns out I couldn’t afford it until I turned 40.

The vagaries of life and finances conquered—and inspiration sparked by a grad school friend who had just begun her instrument training in Colorado—I was ready to fly. I thought I was ready to fly.

I was prepared. I’d gotten my third class medical exam out of the way before scheduling my first lesson, on the advice of my soon-to-be instructor, who does not like to see students waste money and time on training, only to be stymied by a failed medical before their first solo. I’d started reading my textbooks. I’d been in small airplanes many times before, and knew I loved being in the air more than anything else.

So it was unexpected when, before I even got into the cockpit, a storm of apprehension began to brew. I’ve dwelled on that day, and I can’t pinpoint exactly what rattled me. Maybe it was the wind. The METAR when I arrived gave the winds as “33015G20KT” and “30017G24KT” at the end of my lesson—a respectable crosswind for takeoff and landing on Runway 36.

Maybe it was just getting into an unfamiliar cockpit with a total stranger. I’d flown only with family and friends before; I noticed every crack and dent in that airframe and instrument panel during preflight. Maybe it was having a fully-developed frontal cortex and an adult life filled with world travel and people experience that put my senses on high alert. Was this instructor conscientious enough?

I was certainly afraid of causing an accident out of ignorance. What if I did something unrecoverable? It’s also possible I was simply excited. It’s an odd feature of excitement and trepidation that it’s sometimes hard to distinguish between them.

Whatever it was, it blindsided me, and I spent that lesson wrestling with nerves. After takeoff, my mind went blank for what felt like minutes, but was in reality about three seconds. Everything felt overwhelming. The instruments lost their meaning, briefly. I was at war internally over whether I wanted to be in the air or on the ground: the answer was yes. I now understand that I was experiencing task saturation for the first time.

I admitted my jitters to my instructor. He was quick to reassure me that even if the engine failed, we wouldn’t fall out of the sky. He explained the 172’s positive dynamic stability, clearly introducing the term, giving me a definition, and then demonstrating it.

Not really understanding why I was feeling rattled, I couldn’t articulate it very well. “It’s not the airplane I’m nervous about,” I insisted. “I’ve been in small airplanes before. It’s me.” He took that in, and did not try to talk me out of it, but I think he must have been a little bemused.

I asked him to take over in the pattern and land; he directed me to keep my hands on the controls and demonstrated his technique with a running narration. The gusts buffeted us, and he executed a precise crosswind landing with one main wheel squeaking gently onto the runway before the other, followed by the nose wheel. I was fascinated. I was terrified. I wanted to do that. But I also wanted to bail out of that cockpit and never get back in.

When my instructor eyed me doubtfully and asked if I was coming back for another lesson, the 17-year-old won out. “Yes!” I told him. “You’re nuts,” I told myself.

I went home, and found myself afflicted with the peculiar pathology of aviation. I ran out in my stocking feet to look up at airplanes flying over my house. I started reading NTSB reports. I had trouble conversing with anyone about anything except airplanes. I began reading about stalls and watching the University of Iowa’s The Secret of Flight series with Dr. Alexander Lippisch. His visualization of fluid dynamics helped me grasp stall characteristics, and, oddly enough, the lesson in which I first practiced stalls was the first lesson I enjoyed without reservation. I was learning control, and the limits of control surfaces, which I found deeply reassuring.

It took four lessons to feel comfortable with my instructor and the airplane, to feel tentatively sure I wouldn’t do something incredibly stupid and ruin everyone’s day, and to trust our airfield’s mechanic—who has been doing his job since before I was born—with my life.

Looking back on my journey thus far, I have warm and fuzzy feelings even for those tough first lessons. Trepidation can enhance our senses and lends an extra layer of seriousness to the task at hand. Those first few lessons are seared indelibly in my mind. And because I conquered my self-doubt and broke through to the joy and wonder of flying, I can say I’m proud of myself for sticking with it. And no matter what I experience in my journey in the future, I will never again feel that heady blend of terror and excitement, newness and joy. On one hand, I’m thankful for that. On the other, it’s a little bittersweet knowing that the threshold of adventure is behind me.

I’m not going to be the first person on Mars, and I’m certainly not the first person to take flying lessons. I’ve not done anything particularly remarkable in aviation. And I’m content with that, for now. I’m living my dreams. Maybe another student out there can take heart in the thought that feeling a little rattled sometimes is normal, and potentially even beneficial when you’re learning to fly.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox