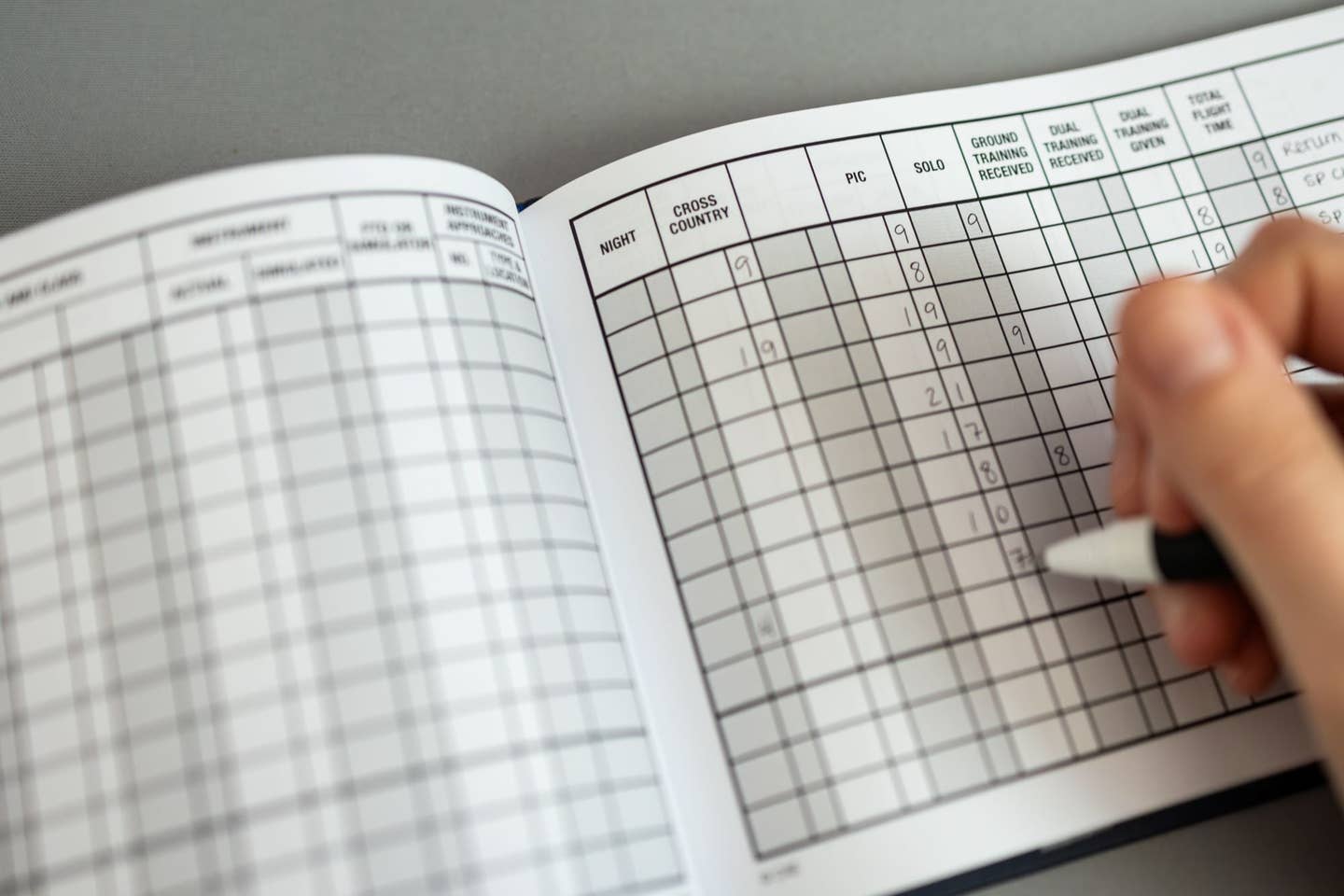

John Harlin III, playing at the controls

of his dad’s trainer at Hahn Air Base in

Germany, developed his skills at risk

assessment as a mountaineer.

The idea was to get away. We'd just learned that the life of the engine in our Cardinal ¡ha terminado! And, even after we decided what to do about replacing the engine, it would be some time before we'd be able to fly the airplane again. In the meantime, the IFR certification (transponder and pitot-static system), my FAA physical and the airplane's annual inspection all would come due.

It felt like too much to deal with; we needed something to take our minds off our airplane's afflictions.

Serendipitously, just at the time we got the bad news about the engine, a friend asked if we'd like to take advantage of a vacation rental he had booked but couldn't use. The casita in Oaxaca, Mexico, if we wanted, was ours for a month — from mid-December to mid-January — a good time to escape from my airplane's ills and winter's worst in upstate New York.

The frequent-flyer-mile connections weren't convenient, and we ended up missing a connection in Mexico City, but we eventually arrived safely in the southwestern corner of Mexico for what we intended as a "rest cure." (Despite some incredibly high MEAs — minimum en route altitudes — flying the Cardinal would have been more fun.)

At a jam session of the Bodega Boys, a group of enthusiastic mescal-fueled musicians that play at Casa Raab, a member of the audience on a yearlong "working sabbatical" asked me what had brought us to Oaxaca. When I said "rest cure," he heard "rescuer" and wondered from what calamity we had escaped. I didn't bore him with our airplane problems.

As it turned out, a number of the people we met in Oaxaca were pilots or knew pilots, and all seemed to know Flying magazine. John Harlin III, our host, and said he'd always had an interest in aviation because flying ran in his family. His grandfather pioneered air routes on the Atlantic coast of South America before flying for Transcontinental and Western Air, which became TWA. He eventually became chief of operations for TWA's international division. And John's father flew F-100s in the U.S. Air Force.

Ironically, John Harlin III worked in New York City for CBS Magazine's Backpacker magazine, at the time a stablemate of Flying. Peter Diamandis, then president of CBS Magazines, made a leveraged buyout of the company and started shedding titles. Eventually, the Wilderness Travel Group, of which Backpacker was a member, was acquired by Rodale Press. John, offered a chance to work for Flying and stay in New York, opted to stay with Backpacker and go with Rodale.

Although he is interested in learning to fly, John's overriding passion was and is mountaineering. His father, John Harlin II, was a world-class climber and created a number of new ascents to some of the Swiss Alps' most famous mountains. Tragically, he was pioneering a new direct route up the north face of the Eiger when a frayed rope broke and he fell to his death. The route has been named in his honor.

Talking with John, I was surprised by the similarities between mountain climbing and flying. In addition to reaching heights that offer a perspective that most people who have never slipped the surly bonds will never see, both activities require a proper respect for the forces of nature and the importance of anticipating and dealing with weather. There's no question that mountain climbing — even more than flying — is less forgiving of mistakes in judgment and proficiency. But I was particularly struck by a discussion of risk assessment in a book John wrote titled The Eiger Obsession: Facing the Mountain That Killed My Father.

If, in the following paragraph, you substitute "flying" for "climbing" and "pilots" for "climbers," you'll see what I mean:

"Climbing is a psychological game as much as a physical sport, and as long as we feel in control we feel safe. These climbers all must have made mistakes; that's why they died. I wasn't going to make a mistake; that's why I'd be safe. In order to continue believing this, all I had to do was ignore all the mistakes I'd ever made, and the mistakes better climbers than I had made, too. Being perennial optimists as well as egoists, it's easy for climbers to keep themselves deluded."

In another section he talks about mitigating the risks of climbing, and I couldn't help but think of the way we advise new instrument pilots to develop their weather flying skills:

"I argue that the only way I can rationalize Alpine climbing is by building my skills in relatively safe environments on good rock and solid ice before applying those skills to more dangerous environments."

And finally, in what might be considered a real case of "get-there-itis," he writes about a climb in Tibet with his friend Mark Jenkins:

"We'd reached just over 17,000 feet on our 21,000-foot virgin peak when continuing snowfalls made us fear a trap. … We could keep on climbing in relative safety, maybe even to the summit, but what about the descent? As darkness fell and the heavy snowfall continued, we decided that staying high was not worth the risk. … It had been an interesting test, and we discussed it a lot. We had stopped ourselves based purely on an intellectual judgment — a calculated evaluation of unseen risks. After flying halfway around the world and devoting a month of our lives expecting to attain a climber's ultimate dream — bagging a spectacular virgin peak by a beautiful line — we backed off because of what might be lurking in future snow layers. We felt frustrated, disappointed, and yet pleased that wisdom had prevailed over ambition."

Think about that for a minute. The two had traveled halfway around the world, had spent a month waiting for the weather to be sufficiently benign to make the climb in reasonable safety and then, after assessing the risks, decided not to make the climb.

The next time you're contemplating a "go, no-go" decision, imagine what it took for them to decide to pack it up and call off their ascent. Compare their decision with that so often made by a VFR-only pilot, returning after a vacation and faced with a forecast that calls for worsening marginal weather conditions, who elects to launch anyway. In assessing risk, one question to ask ourselves is: How important is it, really, to make this flight?

Is the inconvenience of having to make an unplanned fuel stop anything like having to abandon a planned ascent after waiting a month? The next time you're tempted to stretch your fuel reserves, consider that it's not enough only to assess the risk, but more importantly, you also have to act on the assessment and make, what Jay Hopkins calls, the "most conservative choice."

John Harlin III's father died in 1966, when John was 9. In 2005, after carefully assessing the risks, John waited out the weather and finally faced the mountain that had "killed his father" and climbed the Eiger. Details and photographs from John's book are available at johnharlin.net.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox