Sisters in Flight

Amelia Earhart wasn’t the only woman to test her mettle in an airplane. She also wasn’t the only one to find a watery grave.

Amelia Earhart’s fame required constant stoking, including a brief affair with the autogiro. [File Photo: Shutterstock]

A year ago, I wrote an article about the 1937 disappearance of Amelia Earhart. In it, I mentioned—along with some general cautionary observations about range—the suggestion of a California Institute of Technology professor and a graduate student that the range of Earhart's twin-engine Lockheed Electra 10 was less than is generally assumed. This mattered because much of the theorizing about what became of the famous aviator and her navigator, Fred Noonan, depended on their airplane’s ability to fly several hours past Howland Island, the microscopic excrescence of coral on which they intended to refuel before continuing to Honolulu.

My article drew a testy reply from Ric Gillespie, who has probably devoted more time to this subject than anyone else on Earth. His basic complaint was that my comments about the fate of Earhart and Noonan were half-baked and firmly based on my far-reaching ignorance of the topic. This I conceded. There followed a cordial exchange of emails and a copy of his book Finding Amelia, as well as several issues of Tighar Tracks, the journal of the aviation-archaeology group of which Gillespie is the head.

"Women certainly have the courage and tenacity required for long flights."

Mildred Doran

Finding Amelia is a densely documented, finely detailed and well-written book. First published in 2006, it does not include accounts of subsequent investigations that have bolstered Gillespie’s theory that the Electra ended up more or less intact on a reef on Nikumaroro, formerly Gardner Island, an atoll 350 nm south-southeast of Howland. A few shreds of physical evidence support this claim, together with a number of radio messages heard by ham-radio operators in various parts of the world during the days following the disappearance.

Personally, I remain skeptical—not because of what was found but because of what was not. The absence of substantial wreckage, including two big Pratt & Whitney radials, while not conclusive, suggests to me that the Electra wasn’t ever there.

But Gillespie disagrees, and he knows much more about this than I do.

Amelia Earhart herself does not emerge unscathed from Gillespie’s narrative. Initially borne on the wave of enthusiasm for aviation (particularly for long ocean crossings) that was engendered by Lindbergh’s 1927 solo flight from New York to Paris, Earhart parlayed her charm, connections and physical similarity to Lindbergh—youthful, gangly and tousled—into an international celebrity that required constant stoking with new publicity. Lots of people wanted—or felt obliged—to help her, but she did not help herself. The single most important cause of her failure to locate Howland Island seems to have been her faulty understanding of the characteristics of her own radio equipment and that of the Coast Guard ship that had been stationed there to assist her. She did not know which frequencies to use for direction-finding. The knowledge was available, but she seems not to have made a serious effort to master it.

In the interest of full disclosure, my own flight planning has at times been pretty slapdash. But I didn’t disappear, so nobody noticed.

Earhart represented the tail end of a distance-flying craze that lasted a decade. Many who had participated in it shared her fate, including a number of women who hoped to stake out some feminist territory in the generally masculine realm of aviation. For every flight that succeeded, two or three failed. Failure meant disappearance; the ocean kept its secrets close.

One young woman who preceded Earhart to a watery grave was a Flint, Michigan, schoolteacher named Mildred Doran. The 22-year-old Doran was enthusiastic about flying and persuaded the owner of a local oil company to sponsor an entry in a California-to-Hawaii air race that had been announced by James Dole, the Hawaiian pineapple magnate, shortly after Lindbergh’s flight. Not a pilot herself, she would ride along as a passenger. As with Earhart, the link between a great challenge and the money needed to confront it was supplied by somebody’s desire for publicity: The Lincoln Oil Co. of Flint would get a lot of print from the attractive and articulate “flying schoolmarm,” and the air race itself would boost public awareness of Dole’s pineapples.

The date of the race was set for August 12.

“Both the pilots and the crowd urged Mildred Doran to stay behind, but she climbed into the back seat of the Buhl.”

Somewhat awkwardly for Dole, on June 28 two Army pilots, Lester Maitland and Albert Hegenberger, took off from Oakland, California, in a Fokker trimotor and arrived in Honolulu 26 hours later. Two weeks after that, Ernie Smith and Emory Bronte—the latter evidently the son of a Wuthering Heights fan—made the flight in a single-engine Travel Air, which ran out of fuel but alighted safely, if ignominiously, in a clump of trees on Molokai, Hawaii. The virgin route from California to Hawaii was beginning to look rather experienced.

You would think those two successful flights, added to the failure of Lindbergh himself to enter the race, might have taken the wind out of Dole’s sails, but no—the die was cast. If anything, the 2,400-mile flight now seemed less hazardous than before.

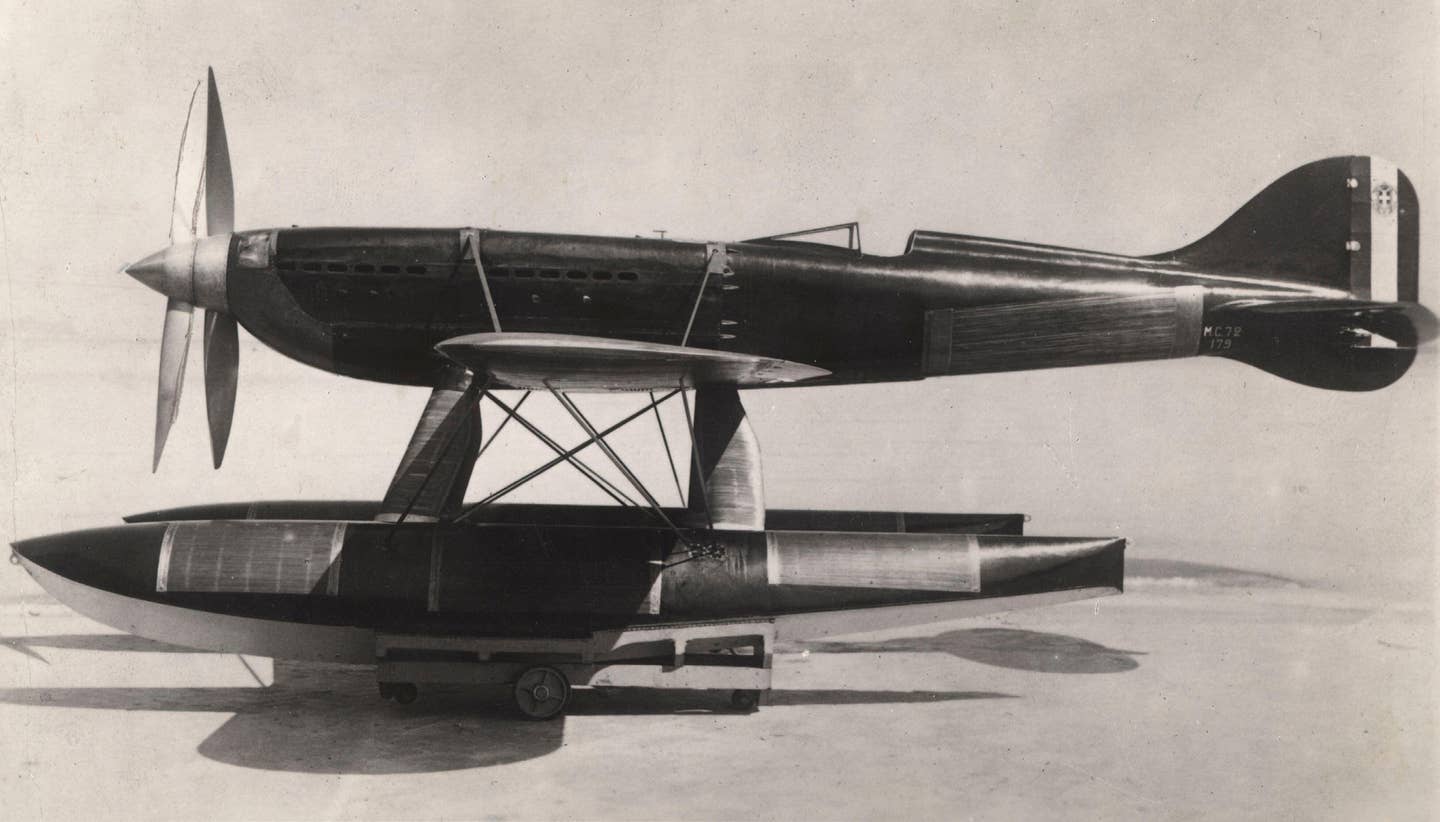

Of the motley swarm of 15 airplanes and crews that entered the race, some were quite plausible: the Lockheed Vega prototype, a Spirit of St. Louis look-alike called Dallas Spirit, and the Phillips Petroleum-sponsored Travel Air 5000, Woolaroc. Most entrants were high-wing monoplanes in the style of Spirit of St. Louis, but the Lincoln Oil entrant, a Buhl Airsedan christened Miss Doran, was a sesquiplane (a biplane whose lower wing is much smaller than the upper). There was one twin-engine triplane that ended up in San Francisco Bay, the crew wading safely to shore; three other contestants were not so lucky, dying when their airplanes crashed on the way to Oakland.

The race was delayed for several days when the newly formed Aeronautics Division of the Department of Commerce—later to become the FAA—imposed a number of rules and requirements on machines and participants the majority could not meet. Frank Phillips, the Dallas Spirit sponsor, inveighed against government meddlesomeness, as befitted his role as a self-made Texas oilman, but at least one of the requirements seems sensible enough: An airplane had to carry enough fuel to reach Hawaii, with a reserve.

Huge crowds came out to witness the departures. The first airplane to take off, a Travel Air, soon turned back with engine trouble. The next two crashed while trying to get airborne, but their crews were unhurt. Next, the beautifully streamlined yellow Vega Golden Eagle got off without trouble, followed by Miss Doran,which promptly returned with a sputtering engine.Three big monoplanes then went off, the last of which, Dallas Spirit, soon came back with fabric damaged by a badly secured access panel. Miss Doran, its engine problem fixed, was last to leave. Both the pilots and the crowd urged Mildred Doran to stay behind, but she climbed into the back seat of the Buhl. She was ashen-faced and tearful, some said, but determined to carry on.

The next day, Woolaroc touched down at Honolulu before a huge crowd. Two hours later, Aloha, which had taken off just before Woolaroc but navigated less precisely, arrived to the vast relief of the pilot’s frantic wife.

In vain, the crowd searched the sky for the other two contestants, Golden Eagle and Miss Doran. They never came. Two days later, Dallas Spirit,with two aboard, took off to search for survivors. As the airplane zigzagged westward, it sent out a series of jaunty Morse code messages, and then, “... --- ...” in a final SOS.

Nine men and the young, brave and tenacious Mildred Doran were lost in the Dole Transpacific Derby.

As to the pineapples it caused to be sold, their number is not recorded.

Editor's Note: This article appeared in the December 2021 issue of FLYING.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox