Finding one lake among hundreds can be a challenge. Flying

“It’s that lake right ... there,” he said. When he removed his finger from the chart, all I could see was a mass of hundreds of lakes.

It was to be our briefing for the flying adventure of a lifetime, but it was occurring in a restaurant bar, and it was clear that by the time we got there our briefers were ahead of us on having a good time.

We were to land a Cessna 185 on floats on a little lake on the North Slope of Alaska to retrieve a couple who had been camping and fishing. Our briefers were full of warnings: “Watch out for that lake. It’s just barely long enough.” “Be careful of that submerged rock. There have been a couple of airplanes that have lost floats on it.” “Brown bears are all over the place.” “Don’t try to go through the pass in too low of weather.” “You can get trapped up there for weeks.”

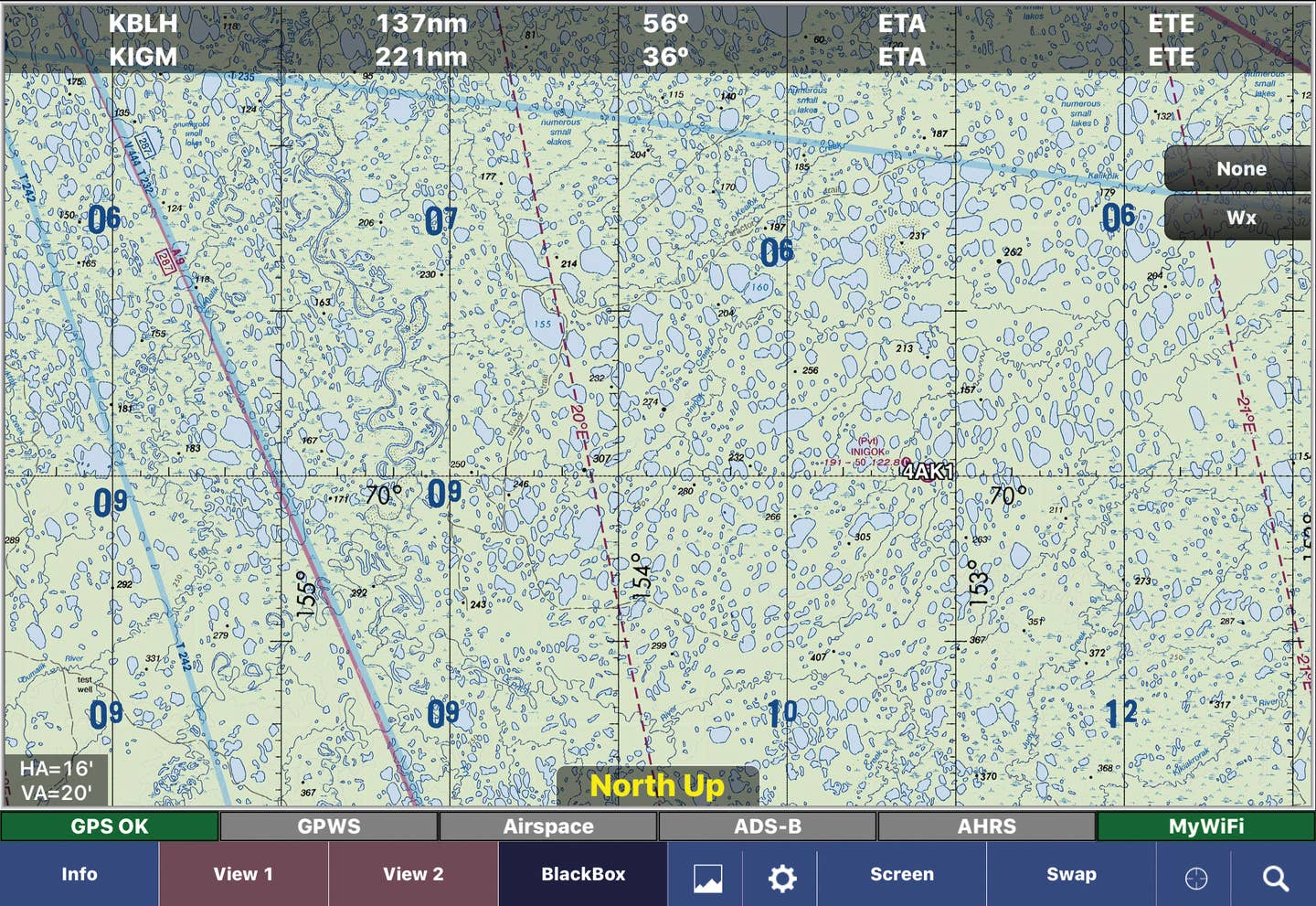

Our plan was to take off from the Chena River in Fairbanks. Then we would land and pick up fuel stashed at another lake north of the Arctic Circle called Long Lake. Then we were to cross the Brooks Range through a pass to the North Slope and, without VOR coverage and in the days before GPS, find our particular lake out of hundreds in the area and miss the submerged rock while landing. Then reverse the sequence going south.

The first time we tried it after we picked up some of our stashed gas, the weather prevented us from making it through the pass. We returned to Long Lake and hunkered down in a little plywood cabin.

Two days later, we decided to try it again. This time we just made it through the pass. After Martha deftly avoided the submerged rock on landing, I pointed out the brown bears on the shore as we water-taxied over to pick up the couple. They scurried about their little plywood cabin gathering everything up.

We were all eager to leave as soon as possible. The couple, in particular, didn’t relish being trapped there any longer. On the return trip, as we approached the pass, we could see that, once again, we were going to barely make it through.

Just as we were starting into the pass, the wife exclaimed, “Oh! I forgot my ring! It’s back in the cabin.” I felt like a heel, but I said, “I’m sorry, we can’t go back for it. I don’t know whether we will be able to get through the pass the next time we try. We can’t afford to use fuel going back and forth. The next people there will bring it back for you.”

In spite of leaving the ring behind, the couple was glad for the experience — and equally glad to be back in Fairbanks.

The trip was exciting for all of us in different ways. For Martha and me, it was a wonderful exercise in bush and off-airport operations. It helped illustrate the additional planning and thoughtfulness required to mitigate the risks involved.

The biggest concern lurking behind everything we did was fuel. The alternates were very far apart, and because our landing areas had no IFR approaches, we were restricted to VFR.

VFR through the pass was obviously iffy. Our success ratio in getting though the pass on the outbound leg was one out of two. We had no idea how many attempts, and how much fuel, it was going to take on the way back. The routine of getting gas at every opportunity was critical.

There is a plethora of unknowns when you’re operating off-airport. Of course, neither one of our remote landing areas had weather reporting or communications. It was just a case of flying there to see what the conditions were. When we arrived, we had to figure out the wind for landing on our own. In the case of a lake, it is pretty easy. The waves are perpendicular to the wind, and the shore with the smooth water is upwind.

It’s harder to figure out the wind when you’re operating off-airport on land. Of course, you can still look at the wave pattern on a lake if there is one nearby. Otherwise, you can look for dust, smoke and the way vegetation is blowing. As a last resort, you can fly a rectangular pattern around a landing area and observe your crab angle on each leg.

When Martha and I were flying a blimp regularly, we realized that the pilots who were picked to pilot them had significant experience in flying that required high sensitivity to the wind — and were proud of it. One of the more fun blimp pilots also flew as a copilot for an airline. One day on final, he could see the waves on a nearby lake and the smoke trailing away from a smokestack. When the captain told our buddy to call for a wind check, he replied, “I am not going to embarrass this airline by asking for a wind check under these circumstances.” I don’t know how long he kept that job.

Another risk of operating off-airport is that there is so much you don’t know about the landing area. In some cases, you don’t even know for sure how long the landing area is. Martha and I used to fly over lakes we were thinking about landing on and record the time it took us to fly the length both upwind and downwind at 60 knots. The average number of minutes gave us the length of the landing area in nautical miles.

When you are landing at an airport, folks have gone out of their way to make sure you have clear approaches and departures. Off-airport, you’re on your own. To check the area before landing, we were taught that we should first do a high reconnaissance and then do a low reconnaissance of the landing area.

We became believers in that concept after one occasion, while flying a helicopter, I decided on an impromptu basis to do a landing and some hover work in a field for practice. We noted some power lines crossing the valley, and I told Martha that my plan for departure was to fly over the top of a power pole on the theory that the line would not be higher than the top of the pole.

As we approached the pole, Martha started hollering urgently, “Pull up! Pull up!” I found this annoying since I had already explained my plan. But something about the urgency in her voice made me pull up anyway to discover that I had just barely cleared a line that had skipped that particular pole. It wasn’t fair. Lines are never supposed to be higher than the tops of the poles. A high reconnaissance would have prevented all the fuss.

The low reconnaissance also helps check the surface area. In a helicopter, we always think about whether dust will blow up and effectively blind us, or whether mud could grab a skid and cause the rotor lift to roll us over. For landing a skiplane on a frozen lake, we were taught to first make a pass in which we dragged the skis slightly and then come back to check if there was water in the tracks — a sign of weak ice and a bad thing if you are landing on a supposedly frozen lake.

At airports, the operators usually make a sincere effort to clear the area of mobile hazards; for instance, bears and other animals. Conversely, we didn’t get that help when we used to land routinely on the Kenai River in the 185 on floats. Not only did we have the problem of rough water from the boat wakes, but we also had the problem of boaters in a party mood who thought it was cool to race a 185 on floats. We never knew what they were going to do next.

Off-airport operations can take you places and give you experiences that are unparalleled. They can also be risky. They require considerable thought on how you are going to mitigate those risks. It is wise to build up to off-airport flying gradually and have a mentor along the way. In the process, you’ll become a more skilled and situationally aware pilot in your flying — and have a lot of fun!

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox