Recalling the Speed Rules of the Past

Schneider Trophy air races led the way to a place where no one goes.

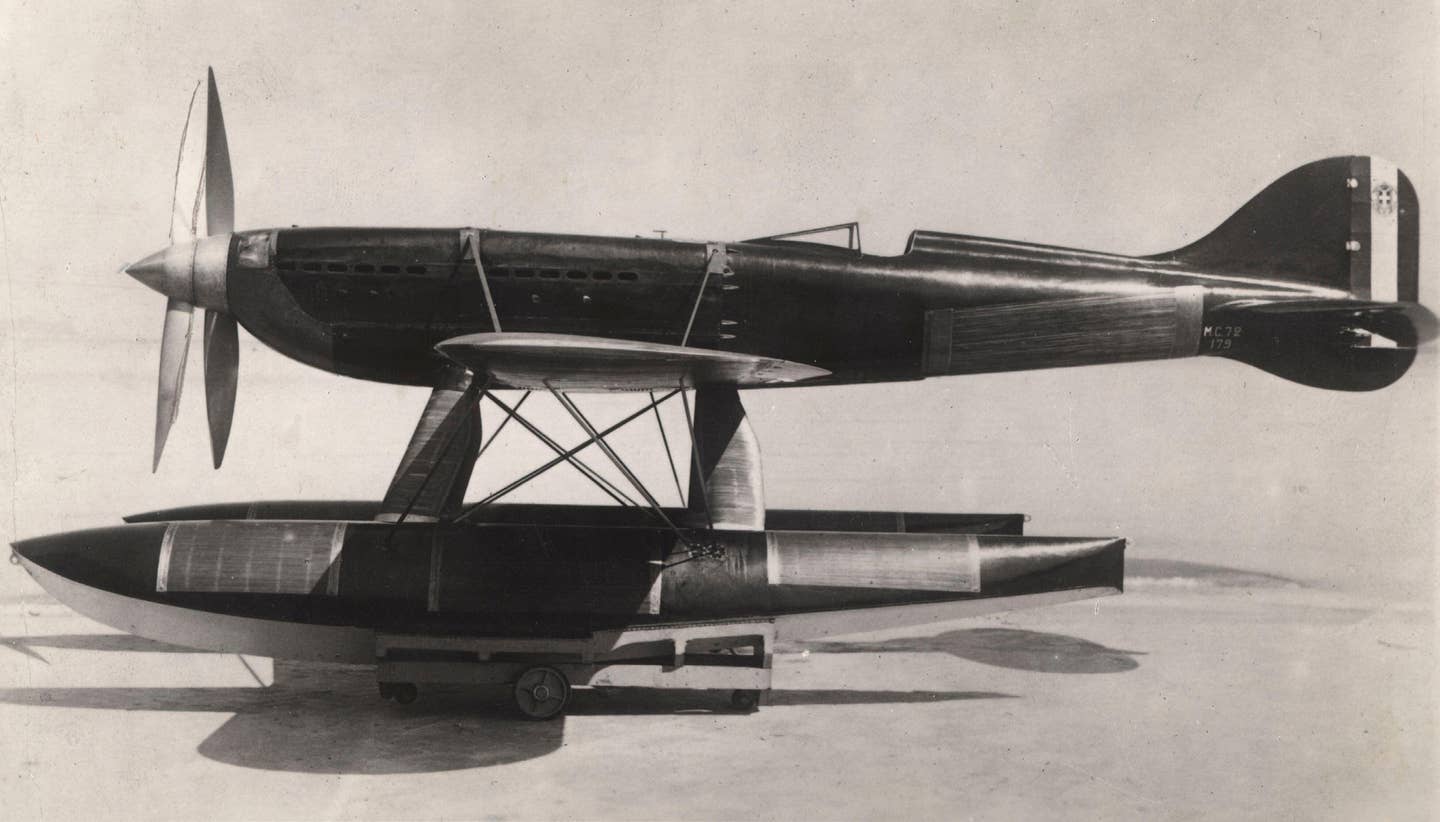

Francesco Agello’s small—31-foot span—and elegantly shaped Macchi M.C.72. [Alamy]

In fall 1935, an Italian pilot named Francesco Agello set a speed record that has remained unsurpassed for 90 years. In fact, it will probably remain that way forever. It is the mark for hyper-fast piston-engine seaplanes, and they have gone the way of velociraptors.

Agello’s small—31-foot span—and elegantly shaped Macchi M.C.72 had two 12-cylinder engines bolted together end to end driving steeply pitched, contra-rotating propellers through coaxial shafts. By then, streamlining had gone as far as it could and speed was all about raw power.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowThe Cessna 152-sized M.C.72 had 3,100 hp. Despite the drag and deadweight of two 20-foot-long pontoons, the mark (441 mph) was for several years the absolute world speed record not just for seaplanes but for all airplanes.

It was a time when aeronautical progress was spurred by numerous contests and generous prizes, and flying exhibitions and races, seasoned with a pinch of mortal danger, drew huge crowds.

The M.C.72 ended a saga that began in 1912 when a French pilot, balloonist, and financier, Jacques Schneider, established a 25,000 franc prize—more than $100,000 today—for an annual seaplane race. In addition to the cash prize, the winner would secure possession, for the year, of the Schneider Trophy, an oddly erotic art nouveau monstrosity now on display at the Science Museum in London. If the same team won the trophy three years in a row, the contests would end.

Over its two-decade run, the Schneider Trophy became the most famous and prestigious of aeronautical competitions. It evolved into a feverish struggle among nations, with governments, military services, and wealthy citizens contributing financial support.

In 1912, when airplanes did not fly well and it was considered remarkable that they could fly at all, operating on water added further complexities, not the least of which was that of pronouncing the species name of hydroaéroplane. The first seaplanes were land planes whose wheels and skids had been replaced by weirdly shaped floats. The science of planing hulls was in its infancy, and getting up off the water and then back down while remaining upright and dry required a good deal of both skill and luck.

The Schneider contests were time trials, not races. The contestants took off successively and flew a number of laps on a triangular course over water. The original rules required a course of at least 170 miles. This grew to 350 as speeds increased.

The earliest Schneider Cup airplanes were powered by rotary engines—those curious World War I-era radials whose crankshaft was bolted to the firewall while the cylinders spun around it. Most were wing-warping monoplanes, their wings braced above and below by wires. Maximum speeds were on the order of 50 to 75 mph.

- READ MORE: They Just Didn't Have the Wright Stuff

The second race, which took place at Monaco just months before the outbreak of World War I, ended with a movie-worthy upset victory by a tiny sport biplane from England, the Sopwith Tabloid. (The name referred to a small pill, and only later came to be applied to half-size newspapers.) The contest airplane, originally equipped with a single medial pontoon, overturned and sank in a river shortly before the race. Fished out and dried, and with its pontoon sawed lengthwise into two, the dark horse Tabloid easily won at 86 mph, nearly double the winning speed of the previous year.

Interrupted by WWI, the contests resumed in 1919 at Bournemouth on England’s south coast. Wartime technical advances had increased the reliability of aero engines and raised their output from 100 to 450 hp. Large liquid-cooled, in-line vee configurations supplanted rotary engines, whose growth potential was limited. Airframes, built of wood, steel, and cloth, were strong and streamlined, and floats and hulls had reached a satisfactory state of hydrodynamic efficiency.

The contestants at Bournemouth, all biplanes, were of two types—floatplanes and hull-in-the-water flying boats. The flying boat had some apparent advantages in that it had only one body to drag around, not three. A single hull was easier to manage on the water. The engine, perched between the wings (which in turn perched atop the hull), was near the center of gravity, and so as larger engines became available they could be installed without disturbing the balance of the airplane.

On the other hand, the hull had to be quite large to provide sufficient buoyancy for heavier and heavier engines, and, since much of the weight of a flying boat goes into making its hull able to withstand water impact, a large hull added unwelcome weight.

- READ MORE: Explaining the Fiction of Minimum Speed

Italy won at Bournemouth, as it did the following year at Venice, Italy, where the only participants were a handful of Italians. The next year, at Naples, Italy, the British firm of Supermarine (I suspect compelled as much by desire for publicity as by patriotic fervor) joined the fray with a biplane flying boat, the Sea Lion II. It was an ungainly thing, but its 450 hp Napier engine propelled it to 145 mph and victory.

The name Supermarine is linked to the Schneider Trophy through the person of the firm’s chief designer, Reginald Mitchell. Mitchell is famous for a later design, the Spitfire, an airplane that, unlike all too many things and persons today called “iconic,” truly is iconic. The creation of an airplane is a cooperative activity, however, and as it happens the most iconic thing about the Spitfire, its elliptical wing, was designed not by Mitchell but by aerodynamicist Beverley Shenstone.

It’s often said that the Spitfire was a direct descendant of the Mitchell-designed S-series airplanes that retired the Schneider Trophy in England in 1931. That claim, while appealing, does not strike me as persuasive, because when, in the early 1930s, the Royal Air Force asked Mitchell to design a fighter, his first attempt was a homely fixed-gear, open-cockpit thing with an inverted gull wing and no apparent kinship with his beautiful Schneider designs. His Type 224 was an all-around disappointment. Mitchell returned to his drawing board, and the Spitfire was the result.

Until he designed his triumphant series of Schneider Trophy planes, Mitchell’s work had consisted mainly of biplane flying boats for passengers and cargo. It was not he but the Italians who, in 1926, first ditched the hull and the extra wing and brought the trophy home with a low-wing monoplane on floats, the Macchi M.39, designed by Mario Castoldi. (The record-setting M.C.72 was a direct descendant). Mitchell, recognizing a good thing, adopted the same configuration.

Huge sums were expended in the Schneider contests, lives were lost, airplanes wrecked, and national prides inflated and punctured, all in a pointless struggle to combine extreme speed with seaworthiness. And yet, when it was all over, the most important question was left unanswered: How fast would they have been without the pontoons?

This column first appeared in the December Issue 953 of the FLYING print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox