** To see more of Barry Ross’ aviation art, go

to barryrossart.com.**

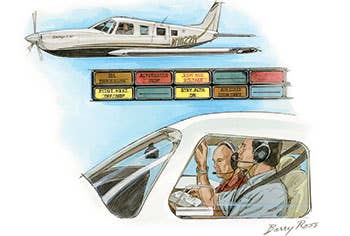

Several years ago my uncle and I flew up to Boston to pick up our new company airplane and fly it back to Georgia after the installation of an ice-protection system. We had dropped the airplane off two weeks earlier — a milestone for me as a pilot and my uncle as a student pilot, as it was our first flight through the busy East Coast airspace.

Though both of us originally were Northerners, we had spent most of our flight time in the South, where the controllers manage to convey their instructions at a snail’s pace. But combine rapid fire communications with courteously delivered but seemingly endless amendments to our planned flight route, and you have a recipe for an exciting flight with little time left for sightseeing!

The first third of the return trip was uneventful. We flew over Long Island, over the top of JFK — at which point my uncle couldn’t stop saying, “Unbelievable, the jets are landing and taking off directly under us!” — paralleled Manhattan, and then turned slightly inland over New Jersey, per ATC’s latest amendment to our route.

Though it was a beautiful, clear day, we were caught in the moderate chop forecast in the day’s airmet from the surface to 10,000 feet. It was the kind of chop that forced me to sit low in my seat, with my seatbelt tightly fastened, so I could minimize the number of times my head and the top of the cockpit met with an unfriendly thump. In an effort to discover smoother air, we asked ATC for, and were eventually granted, a climb from 6,000 feet to 10,000 feet. Once we were established in the climb, I made an “it seemed like a good idea at the time” decision to test the new TKS system.

I looked out at my wings, admiring the shiny, new leading edge afforded by this technological innovation. Dubbed the “PIIPS” (Piper Inadvertent Icing Protection System), this equipment is designed to cover the airplane with glycol, an antifreeze solution, through a porous titanium plate along the leading edge of the wings and tail, and through a slinger on the propeller. Although I am told that the same system is certified as known-ice equipment in Europe, it is approved only for use during accidental encounters with icing conditions in the United States.

As we were leaving, the installers recommended that I cycle the system every two weeks or so to keep the lines clear and to verify that it functions properly. Wasting no time, I advised my uncle of my intentions, flipped the switch to “Norm” and scanned for evidence of glycol. The fluid came out as promised, slowly coating the airplane with a comfort-inspiring viscous solution that prevents ice from adhering to the airframe.

Two minutes later, our peaceful climb was interrupted by a “THWACK!” from somewhere in front of us. “What was that?” my uncle said, with obvious and reasonable concern on his face. “I’m not sure,” I replied in my best captain’s voice. He said: “Was it a bird strike? Did we throw a rod?” The engine purred along as before, but just when I was about to assure him that all was well, the alternator warning light and horn came on, dashing my hopes that there would be no further repercussions from the disturbing sound we heard.

The emergency training my instructor, Lucas, had drilled into my head quickly took over. I made sure that I kept control of the airplane instead of falling prey to panic or distraction. I then handed my uncle the POH that sat between us and asked him to read the procedure for a failed alternator to me, to confirm that my memorized steps were accurate. He did a wonderful job, given the circumstances, calling out each step:

Uncle: "Verify failure ... check ammeter."

Me: "Failure verified."

Uncle: "If ammeter shows zero, ALT switch off."

Me: "ALT switch off."

Uncle: "Reduce electrical loads to minimum."

Me: "Loads reduced."

Uncle: "Check and reset ALT circuit breaker if required."

Me: "Checked."

Uncle: "ALT switch on."

Me: "ALT on."

Uncle: "If power not restored, ALT switch off."

Me: "No power, switching ALT to off."

Uncle: "If alternator output not restored, reduce electrical loads, and land as soon as practical."

Me [thinking to myself]: "If ever there was a time to yell 'uncle,' this was it!"

Keeping to my course, I focused my attention on the moving map display to determine the nearest airport. I then called ATC, advised them of the sound we had heard and asked to divert to the nearest airport to inspect the problem.

We followed the emergency procedure Piper had carefully detailed in the POH, landed at the nearest airport and shut the engine down. After removing the cowling with the help of a mechanic who happened to be at the airfield on a Sunday morning, we discovered that the alternator belt had broken in flight, striking the cowling as it went, which produced the loud noise we heard somewhere northeast of Washington, D.C.

The mechanic assured us that it was no big deal, especially given that we had a backup alternator. He handed me the shreds of the alternator belt he had picked out of the engine compartment and added, with an air of nonchalance that only old-school pilots and mechanics can muster, “My cousin once flew from Santa Monica to New York without a radio or a transponder. You’ll be fine.” It was one of those well-intentioned comments that did little to appease the apprehension I felt about having to fly into the Washington, D.C., ADIZ on my way to the Piper dealer ... on a backup alternator.

After stopping for pizza at the airport restaurant — which, incidentally, is where we confirmed we were in New Jersey when the waitress said, “How are yous guys today?” —we flew to another nearby airport for the repair. One week and two commercial flights to and from Atlanta later, the airplane was good to go.

Eager to determine what caused the belt to break in a new airplane, I asked the shop foreman to show me exactly what he determined to be the cause. He took me to the front of the airplane, had me look at the narrow space between the back of the propeller hub and the cowling, then pointed out that the tube feeding the prop slinger (basically a ring with a channel on its underside) was misaligned when the anti-icing system was installed. When I turned the system on, it didn’t feed the glycol into the prop slinger. Instead, it sprayed the slippery solution all over the front of the engine, including the alternator belt!

Once coated, the belt no doubt began slipping, built up heat and broke, causing the alternator failure. I have since added an item to my checklist before every flight, of course — namely, making sure the feeder tube is properly aligned with the slinger ring.

I learned from this experience that extra attention and caution is required during the break-in period of anything new, and that it is important to run tests of those new systems in as controlled an environment as possible. I can only imagine if my first use of the system had occurred in IMC conditions, with ice building on my wings. My second and subsequent tests of the system were performed at 5,000 feet, within gliding distance of my home field.

I was also reminded of the importance of staying cool, calm and collected when the unexpected happens. Don’t hesitate to use all resources at your disposal (such as equipment, ATC, copilot and passengers) to finish the flight safely. Finally, I learned that I can — and should — add items to my preflight checklists as experience dictates.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox