Illustrations by Matthew Laznicka

Air traffic controller Ray Smid watched the yellow blips slide across his radar screen. The circles moved in silence, but Smid never forgot that they embodied real aircraft. It didn't matter if the traffic was big or small. Lives were lost if the blips merged.

The eraser-shaped images toted "data blocks" displaying flight number, destination, speed and altitude. Aircraft climbed and descended; others were at cruise altitude. Smid's flat-panel display constantly changed. The traffic never stopped.

It was 5:20 a.m. on Sept. 26, 2014, and while Smid couldn't see the sunrise from the dim control room at the Chicago Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC), blue sky waited at the end of his shift. Smid had been a controller at the Aurora, Illinois, facility for the past 27 years. Unlike airport control towers, Chicago Center and its counterparts in places like Minneapolis and Indianapolis are housed in nondescript buildings far from runways and taxiways.

Chicago Center (ZAU) is one of the world's busiest ATC facilities. Smid and 400 other controllers handle 6,300 aircraft per day transiting its massive airspace enveloping parts of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin. The primary challenge is handling "transitions" — aircraft climbing and descending into the juggernaut of massive airports, Chicago O'Hare.

The control room operates in quiet repose despite the fast-paced workload. Controllers roll track balls and tap keyboards to update their data blocks; humming equipment fans cool the square-orb screens. Confident voices harmonize with the electronic chorus. Tone, volume, pitch and tempo make the difference. A controller's voice ultimately controls the traffic.

"If a pilot detects any kind of hesitancy or nervousness, what are they going to be thinking up in the air?" Smid asks. "They're going, 'Do I really want to take this clearance?'"

A controller's worst nightmare is being cut off from his traffic. Broken radio frequencies silence their voices and those of the pilots above. The airplanes, yellow blips on a screen, keep flying; the invisible airways above are impervious to silence.

Smid couldn't have known it, but in a matter of minutes the nightmare would come true. He and his fellow Chicago Center controllers were cast into deafening silence.

The LED fire alarm lights started flashing at approximately 5:30 a.m. White strobes bathed the control room in sequenced pulses. There were no sirens or bells; nobody smelled smoke. The controllers continued working. Some thought it was an ill-timed equipment test.

Controller Paul Dewitte barely noticed. He stared at his en route decision support tool — a computer screen showing the status of his radar and frequencies. The green messages began turning red in cascading failure. Each indication was accompanied by "pings" resembling pennies dropping into empty glasses.

The veteran controller swiveled his chair and saw his colleagues' bewildered faces. Their screens and radio frequencies had gone dark and silent.

"We're about to go down," he heard himself say.

Dewitte calmly transmitted to the aircraft on his screen. It was a matter of time before his voice was also silenced. He put five flights into holding patterns and instructed others to return to their last assigned radio frequency.

"I concentrated [so] that the instructions [to the pilots] were very clear," Dewitte said, "[and so] that there were no misunderstandings."

Across the control room, Smid pressed his headset's push-to-talk switch. "Spirit [Airlines Flight] 656, how do you read Chicago [Center]?"

The Airbus A319 jetliner was approaching Chicago O'Hare from the northwest after taking off from Portland, Oregon, hours earlier. Its yellow blip slid southeast on Smid's screen. The pilots were not answering.

"Spirit 656, if you read Chicago, ident."

The orange transmit light illuminated on Smid's console but dead air filled his headsets. He jabbed a square-shaped button that connected him directly to Minneapolis Center. The open "shout line" never went off the air. Smid would ask his Minnesota cohorts to contact the pilots.

Silence.

His eyes returned to the Airbus' blip. "Spirit 656, Chicago?"

Smid stood and sent his chair rolling backward. He yanked his headsets from their plug-jacks and shuffled to another workstation. Leaning on the plastic counter, he watched helplessly as the yellow blips kept transiting the screen.

The only voice came from behind him. Operations manager Ian Gebhardt reported that a fire was in the basement. Evacuation was mandatory.

Dewitte meanwhile continued transmitting. He was the only controller in his work area who had functioning radio frequencies. He knew pilots were trained to follow specific procedures if they lost communication with ATC, yet Dewitte felt responsible for ensuring every aircraft was safe before he unplugged.

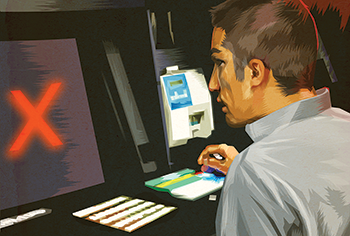

He made a general broadcast to the pilots that could still hear him. Chicago Center was evacuating and radar service was "terminated." He paused and then transmitted: "Good luck." The radarscope went black; then a large red X spread across its screen.

Smid continued standing in his work area; abandoning the pilots wasn't an option. Even if they couldn't hear him, he was still watching. It was horrible knowing the airmen were likely radioing him at that moment. He willed the flight crews to contact Minneapolis Center or another facility.

Just before his screen faded to blackness, Smid saw a welcome sight. Spirit 656's blip turned toward the Minneapolis International Airport. Another controller's voice had reached the aircraft's cockpit.

Smid took a final look at the deadened equipment; his colleagues were already gone. He then calmly walked out of the building and into the pre-dawn darkness.

Bill Cound's Blackberry buzzed against his right hip. The 32-year FAA veteran controlled traffic at Los Angeles Center before trading his headsets for ties and suit jackets. As Chicago Center's air traffic manager, Cound leads the facility's operation, controllers and 200 technical support personnel.

Cound saw the center's number appear on the display. The parking lot was a few streets away; it could probably wait. He continued driving and then unholstered the phone. Minutes could be an eternity in the air traffic world.

Front-line manager Rob Ruegsegger reported that the building had been evacuated because of a fire. Chicago Center was now "ATC Zero." The 24/7 operation was off the air.

"My original take is we've all been through fire drills," Cound remembers. "We'll be back [operating] in five minutes. It just didn't seem like that big of a deal."

Seeing the firetrucks and ambulances through his thin-frame glasses changed his mind. His evacuated employees were congregated in the center's parking lot. Cound began fearing his facility was the epicenter of an aerial earthquake. Flights at O'Hare and Midway airports would be canceled; delays would ripple across the country.

He later sent his wife a text message: "It's going to be a long day."

Controllers Smid and Dewitte were among those grouped in the parking lot. Smid called Toby Hauck, the president of the center's National Air Traffic Controllers Association (NATCA).

Dewitte looked up into brightening sky. The lack of aircraft contrails accentuated the emptiness.

"I knew we were in a very serious situation," Dewitte says. "I just didn't know at the time what the situation was."

He remembered a day when all air traffic stopped; Sept. 11 suddenly didn't seem so long ago.

As the sun rose into the empty sky on Sept. 26, Mike Paulsen, Chicago Center's technical operations manager, adjusted his protective "bunny" suit. The ATF and FBI agents accompanying him had ruled the area a crime scene. White booties paled against gore as they descended into the ashen gloom.

Blood spattered the stairwell. Red droplets trailed along the steps; jagged streaks covered the walls. Acrid smoke remnants choked the cramped corridor. The door at the stairwell's bottom led to the center's "Automation Wing" basement, where Brian Howard, a Harris Corp. contractor, had started the fire and attempted to take his own life.

Dozens of computer racks resembling giant refrigerators lined the aisles. Thousands of cables stretched along the elevated ceiling and under the floor tiles. Paulsen stepped into the facility's nerve center and stared. The white ceiling was covered in black soot; the fluorescent lights were melted. Several computer racks were burned beyond recognition. Spaghetti-snarled wires were charred and cut.

Howard intimately knew the Federal Telecommunications Infrastructure system. He supervised its operation; he installed its components. He also knew how to disable the numerous fail-safe procedures. The fire started where the primary and backup FTI systems converged. Howard pleaded guilty in May and remains in federal custody until his sentencing in September.

"None of us ever saw this coming," Paulsen says. "[Howard] was one of the team." With Chicago Center's vertebrae fractured, it did not take long for the paralysis to spread.

Controllers in places like Moline, Peoria, Grand Rapids and South Bend could see only naked blips on their radarscopes. Without an aircraft's data block, they had no idea what flight they were watching or where it was going. Telephone land lines still connected the facilities, but the severed FTI data streams reduced communication to nondigital platforms.

The Harris-built system is the technical link that fuses the spokes on Chicago Center's operational wheel. Every ATC facility within its airspace is digitally connected through FTI. "It is the hub through which all of our systems communicate," Cound explains. "Think of it as a switchboard."

O'Hare International Airport's control towers have picturesque views. Dan Carrico watched the sun rise over Lake Michigan through the slanted glass. The controller and NATCA representative was poised to help move O'Hare's 2,600 daily combined takeoffs and landings.

Shortly after 6 a.m., the messages began scrolling across the tower's FDIO (flight data input-output) screens. O'Hare was going into a "ground stop." No aircraft were permitted to take off or land at the massive airport.

Carrico read the directive again. O'Hare's bustle was usually impeded only by blizzards and severe thunderstorms. It made no sense.

Text messages from Hauck soon filled in the blanks. The ATF, FBI and police were on site at Chicago Center. Carrico's iPhone later displayed another word: sabotage.

"All that [computer] automation that we had been accustomed to was gone," he says. Almost 2,100 flights were grounded by the end of the day. Carrico and fellow O'Hare controllers prided themselves on moving traffic. The aircraft pileup became a troubling sight.

It took several hours to verify that Chicago Center wasn't at risk of additional attacks. Hauck walked the barren and silent control room floor with an ATF agent. The bomb-sniffing dog accompanying them ignored the half-eaten food littering the workstations. Nearly every radarscope was blank but a few were still powered. Yellow blips and data blocks were frozen in place — ghostly reminders of aircraft flying in Chicago Center's airspace during the fire.

"It was very eerie," Hauck remembers, "especially walking in that room that was completely empty. The lights were still off … and the dog is sniffing."

"It was the first time Chicago Center went dark in over 50 years of existence," Cound adds. "Centers don't turn off."

Some flights resumed at O'Hare and Midway airports later in the day under a dated contingency plan. Large portions of Chicago traffic were allocated to the terminal radar approach control (Tracon) facilities underlying Chicago Center's airspace.

It quickly became clear the situation was untenable. Controllers in some cities were flushed with a 200 to 400 percent increase in flights. Most of the facilities did not operate 24/7 and were minimally staffed.

"[The Tracons] worked airplanes they were never intended to work and were never trained to work," Cound explains.

The SIDs and STARs above became country roads with tollbooths. Flights that did operate flew at low altitudes for extended periods because Tracon radars couldn't track aircraft above 15,000 feet. Airplanes were burning additional fuel that cost the airlines money.

Mike Paulsen soon determined that the FTI system was damaged beyond repair. It would have to be replaced — a massive task that, even with a Herculean effort, would still take two weeks. Chicago Center's management realized the tremendous stakes. The traveling public, airlines and U.S. economy were at risk. Restoring O'Hare and Midway traffic flows was essential.

"The contingency plan was never designed to run normal traffic for an extended period of time," Cound explains. "That was our challenge. The contingency plan let us limp through … [but] we went well beyond [its] constraints and figured out a way to make it work."

The solution was unprecedented in the FAA's history.

"We put experts and professionals together and said, 'What's the best way to do this?'" Cound says. "We removed all of the constraints and they came up with some very creative ways of working traffic."

While Hauck watched the bomb-sniffing dog, controllers across the Midwest already understood the dire situation. The severed FTI system tore a 90,000-square-mile hole into the national airspace structure. Chicago Approach and the other Tracons underlying Chicago Center's airspace slowed the bleeding; neighboring centers in Indianapolis, Cleveland, Minneapolis and Kansas City would complete the tourniquet.

Kelly Nelson and Ron Sekenski manage the Minneapolis Center. They have over 60 years of FAA experience between them; they're also pilots. The two men worked with Cound on a variety of projects through the years.

"Once Chicago Center declared 'ATC Zero,' we started identifying physical assets [at Minneapolis Center] that we could make available to work that airspace," Sekenski explains.

Minneapolis controllers adjusted radarscope range to explore how deep they could see into Chicago Center's airspace. Similar experiments were conducted at Indianapolis ARTCC.

Jim Larson had been a controller at Indianapolis Center since 1988. He sat in front of a radar screen and probed the facility's airspace boundaries. They had once reached farther north into central Illinois. Technology had changed but the original airspace borders could be redrawn.

"We've got the radar coverage; we've got the radio coverage," Larson said to fellow controllers. "We can do this."

Larson's team would soon step back in time. The revitalized airspace was one throwback; the severed FTI automation was another. The controllers' rhythm was disrupted, but Larson knew they could still harmonize. Their voices were always the primary instruments — they just had to play in a different key.

Socrates Passialis, a Chicago Center controller for 30 years and a NATCA representative, walked into Chicago Center early Sunday morning. Two days had passed since the fire.

The center's "War Room" resembled a financial trading pit. Blue tape held paper to the walls; cellphones, coffee thermoses and computers littered the U-shaped table. Tech ops personnel worked one side of the room; controllers utilized the other. Cound and Hauck sat next to each other at the U's bottom. Saturday's traffic flows had improved, but airport monitors were still alight with cancellations.

Their directive was challenging: Help divide Chicago Center's airspace among the underlying and adjacent control facilities to safely restore Chicago O'Hare's and Midway's traffic while the basement was repaired.

On a map, Chicago Center's airspace resembled a giant box covered with three-letter navigation aids and altitude blocks. A rudimentary outline of Lake Michigan hid behind the letters and numbers.

Passialis viewed the sectors like a seasoned architect. He pictured O'Hare's traffic streams coursing through the box. Departures exited the sides; arrivals flushed through the airspace's corners. With Chicago Center being off the air, the map was a giant puzzle consisting entirely of the edges. Collaborating with the other ATC facilities and thinking outside the airspace's box would fill the puzzle's void; however, Chicago Center's controllers were the final piece. Smid, Dewitte and 200 others would travel to 19 other facilities. Nobody knew the airspace better.

Everyone in the War Room, nevertheless, understood the ramifications of redrawing airspace boundaries and sending controllers to different facilities. It just wasn't done — ever.

Airspace changes usually take two years in territorial cultures. Controllers are protective of their assigned areas. (Clearances of aircraft into other controllers' sectors without permission, aka "point-outs," are grave faux pas). Many ATC professionals work the same slice of sky for their entire careers.

Moving traffic through unfamiliar radarscopes was therefore a daunting challenge. The controllers had to learn new positions in an already ongoing and pressure-packed game. Yet no controller refused the transfer requests. Dave Ingraham, a 30-year Chicago Center veteran, only asked when he needed to leave for Minneapolis Center. Hauck's response was the same to everyone: "today."

"People just volunteered," he says. "[Our controllers] just jumped in their cars and went wherever we asked them to go. … It was patriotic. … What all of the facilities that were involved did, what the [FAA] did, what the controllers did, labor and management — it was patriotism. They had a lot of pride in their profession, in their country, and they didn't want to see it fail."

Melding the pieces on Passialis' map was a major step toward restoring O'Hare's and Midway's schedules. The severed FTI system, however, remained a major problem. As controllers like Dave Ingraham settled at other facilities, the radar blips still didn't have data blocks. The aircraft could have been a Boeing 747 or a Cessna 172 — it was impossible to tell.

Telephones were the means to bypass the FTI's disconnected vertebrae. As aircraft transited the airspace, controllers relayed flight data to adjacent facilities via the "shout" lines. Facilities resembled 1980s televised fundraisers. Controllers talking to pilots were the hosts; controllers receiving calls were the individuals sitting on staggered risers.

Dewitte was assigned to the Moline Tracon. A controller's voice from the neighboring Rockford facility constantly filled his earpiece. A blip was pointed out on the radar screen. When Dewitte confirmed the target, the Rockford controller relayed the aircraft's flight number, altitude and cleared route. Dewitte scrawled the information on paper "strip" casings and slid the plastic to his left. Another controller then entered the shorthand into the scope's computer. A familiar and comforting sight appeared on the screen: a data block "tagged" to the blip.

The exchanges were nonstop, and there was no time to reply "say again." The jets that make up the vast majority of O'Hare's traffic screamed across the scopes in three minutes. Moline's six controllers were now handling 900 flights per day — nearly five times their customary amount. Dewitte seamlessly worked side by side with his new colleagues. "Everybody at Moline just banded together," he says. "It was a fantastic experience to be a part of it."

Larson, meanwhile, stood in Indianapolis Center's control room, where every scope was occupied with a mix of Chicago and Indy Center controllers. He couldn't tell the difference between them. The voices harmonized together to keep traffic safely flowing. The telethonlike communications were the revised music key.

"The amount of effort we had was phenomenal," he says. "[I felt] immense pride at the job we were doing — knowing we were moving traffic. … We were doing something that hadn't been done before."

Larson and others are quick to credit technical operations personnel for maintaining the endless verbal exchanges. Many of the microwave-based remote communication links between the facilities (essentially the FAA's in-house phone system) had to be rerouted. Conventional land lines were also affected as Harris Corp. employees negotiated with smaller phone companies to make essential circuitry changeovers. "It was engineering on the fly to come up with solutions," Paulsen says.

The incredible teamwork crystalized four days after the fire, on Sept. 30. Despite the unbelievable challenges, O'Hare Airport was again the country's busiest.

While Chicago Center's airspace functioned through other ATC facilities, its Automation Wing basement continued its restoration. Center tech ops employees, Servpro cleaners and Harris Corp. personnel worked around the clock. More than 100 face-mask-clad workers replaced 20 computer racks and 10 miles of cable. "All of our teams were on adrenaline and people just didn't want to stop," Paulsen says. "We were all leaders."

Harris Corp. restarted its factory in Wilmington, Ohio, to meet the target completion date of Oct. 13. The FDIO equipment that first alerted Carrico to O'Hare's ground stop arrived from an FAA facility in New Jersey on Monday morning. Overnight shipping was not fast enough; FAA employees drove it straight to Illinois.

On Tuesday morning, Cound saw green flashes on the newly installed computer racks. He knew the lights signified only that the system was powered, yet the glimmers signaled progress. A return to normalcy was just over the horizon.

Passialis sat at the operations desk in Chicago Center's control room. It was just after midnight on Oct. 13. A telephone was pressed against his ear as colleagues surrounded the table's L-shaped borders. Cound and Hauck silently leaned on the edges; controller Smid stood alongside.

Tech ops personnel had successfully installed the new FTI equipment; controller Colin Monk tested the radio frequencies via FAA pilots flying "Flight Check" aircraft through the airspace. Controllers sat in front of their radarscopes. Chicago Center was ready to take back its airspace, with detailed protocol.

Passialis breathed. He then let his voice fly across the land line.

"Is Kansas City [Center] on?" he asked.

"Yes."

"Is Chicago Center on?"

"Yes."

"Kansas City sector 1, we would like you to start a normal relief briefing."

The controller in Missouri outlined his current traffic flows and weather conditions. He ensured that the Chicago Center controller understood the scope's picture. "Chicago Center has that."

Passialis nodded. "Thank you, Kansas City. Chicago Center now has our airspace back. Please monitor two [hours] out or until we tell you otherwise."

Passialis switched to a "bridge" line connecting every ATC facility involved in the recovery. Larson listened from Indianapolis Center; Kelly Nelson and Ron Sekenski monitored from Minneapolis. Carrico tuned in from O'Hare tower.

"Chicago now has [its] airspace back from Kansas City Center," Passialis announced. He then repeated the procedure with Indianapolis Center and then moved on to Cleveland's airspace. The exchanges continued until Chicago Center's airspace puzzle was whole again.

The entire process took 40 minutes. Controllers' voices once more murmured through the control room; the illuminated scopes were complemented by unbroken radio waves reaching pilots high above.

In his office, Cound sat in his chair and let the past two weeks wash over him. Brian Howard's actions lurked in the depths of his exhaustion, but they were trounced by the countless examples of perseverance, teamwork and sacrifice. The cooperation to the highest levels of the FAA. "I went the entire two weeks without being told 'no,'" Cound says.

Cound opened his computer's email and began typing, thanking dozens of ATC personnel from 36 facilities. The email's subject was "We're back!"

Back on the control room floor, Cound listened to the cooling fans hum and the keyboards tap. The familiar sounds were comforting, but the controllers' voices resonating through the dimness were the purest sounds. Their radio transmissions would always be the primary beat of Chicago Air Traffic Control Center's drum.

Get online content like this delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our free enewsletter.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox