After we've been flying for a while as pilots, things get a lot easier. Our hands and eyes begin to go to the right places in the cockpit naturally, and the body just knows how much response the airplane will make to each control movement.

We become comfortable with aviation communications. We get to know the local area so well that we can keep ourselves out of trouble even in complicated airspace, often merely by looking at landmarks out the windows. We know where airports are and which ones are suitable for us. On longer trips we have a picture in our minds of the general lay of the terrain and the overall weather patterns, and in most cases the locations of cities and airports even in other states.

All this leaves experienced pilots with the excess mental bandwidth to maintain situational awareness, which, combined with the knowledge they have accumulated over the years, allows them to easily recognize and mitigate risky situations.

A beginning pilot doesn't have all of these advantages. When we first start flying, our brains are almost completely used up just flying the airplane. Add in the need to communicate on the radio and navigate the airplane and there is little brainpower left to spare.

These differences came vividly to mind when Martha and I, and our good friends Tom and Brenda Haines, decided to rent airplanes in Johannesburg, South Africa, and fly through southern Africa for a photo safari. All of a sudden we felt like we were student pilots all over again. The communications, airspace, airports, terrain and weather patterns, even the airplane, were no longer familiar old friends.

We were back to studying charts with symbols we had never seen before and listening to audiotapes to decipher unfamiliar and, for us, hard-to-understand South African communications. The airplane Martha and I were to fly was going to require reacquaintance. It was a trusty Cessna 182 Skylane, but it had been years since we had flown one much, and this one would be heavily loaded. Plus, this trip would depart from Lanseria International Airport, a general aviation airport northwest of Johannesburg with an elevation of 4,500 feet, and the weather was hot.

Our check rides were a combination of instruction and evaluation with the instructor pointing out things we needed to remember about flying a heavily loaded 182 from dirt strips at a high-density altitude. He had us demonstrate dragging the strip before each landing to look for wildlife.

I considered my job was to demonstrate my superior skill at handling the 182. I demonstrated something, but it wasn't superior skill. On the dead-stick landing I decided I should make a turn to lose altitude. It became clear that at that density altitude there was no need for the turn, and I wound up surprising myself at how low I got. It was obvious I really needed the check flight.

To be fair, we didn't do any of this unassisted. We were renting the airplanes from Hanks Aero Adventures, which makes it its business to help pilots learn what they need to do the trip with minimal risk. Hanks had done everything in its power to reduce the workload and mitigate the risks for a pilot completely unfamiliar with the area. It had arranged our instruction on airspace and communications and South African air law, set up our check rides, and administered our required South African Air Law tests.

When it came time to depart, Hanks gave us a package for each leg of our trip that covered every imaginable risk to be managed, and a GPS with every leg of our entire route loaded in. It filed every flight plan for us, and it contacted our destination camps for each leg to make certain we had arrived as expected. In the mornings when we were ready to leave, it made sure we had the latest weather reports and forecasts.

Still, we had limitations we weren't used to. First, we were limited to day VFR by our South African pilot certificates. As pilots who fly IFR almost all the time, this seemed like a severe constraint on our options. Adding to our concern, the inflight weather information that is so readily available to us in the United States simply isn't available in the areas in which we would be flying in Africa.

As the trip progressed it became increasingly clear we didn't have the local knowledge to understand all the risks we would be taking on. First, we didn't know the terrain and the local weather patterns. On our first 2½-hour leg we were to fly over the Drakensberg escarpment from Lanseria to Ngala — an airstrip near the Kruger wildlife preserve. According to instructions from Hanks, the escarpment could be covered with cloud if the wind was from the east, requiring a landing at an alternate airport. We wouldn't know whether it would be necessary until we got there and could see it.

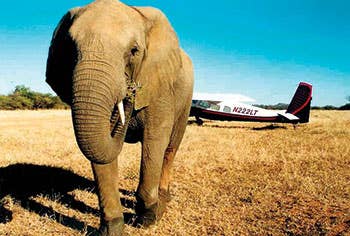

Fortunately the weather was fine, but we encountered other unique challenges on arrival at Ngala. There were impressively sized elephant droppings on the runway, and zebras and wildebeests beside the unfenced strip. Wildlife on the airstrip proved to be a risk for every leg on the rest of the trip. It quickly became obvious that dragging the strip before landing to look for wildlife was a great idea. Since these same animals like to use airplanes as scratching posts, departure called for an especially thorough preflight inspection.

When it came time to leave Ngala there was an overcast layer that prevented us from flying back over the escarpment to Polokwane, which was our fueling stop and departure point from South Africa. We anxiously waited until the weather reports that Hanks sent us each hour let us feel we could safely go. As always, when we got airborne the only weather information we got was what we could see out the window.

Our next leg was from Polokwane to Limpopo Valley, our point of entry to the country of Botswana. We flew five more legs on the trip, which provided us many exciting high points, including seeing elephants from the air, flying over the spectacular Victoria Falls, and seeing amazingly abundant wildlife at every stop, but especially in the Okavango Delta. Throughout the trip I was thankful for the checkout I had received in the Skylane and the reminders about high-density-altitude flying. On more than one takeoff I kept checking manifold pressure and rpm compulsively to ensure the engine was giving me all it could under the circumstances.

On our final leg, our flight back into Lanseria, we were pressed down by a lowering cloud deck as we approached the Johannesburg area. Since we were restricted to VFR-only flying by our South African pilot's certificates, we were concerned about making it into Lanseria VFR and wanted to make a decision about whether to press on while we still had enough fuel to have options. We were too far out to receive the ATIS, so we called Johannesburg Information hoping to get the latest weather at Lanseria. Since "information" was in its name, we thought it would be helpful. The reply? "Listen to the ATIS when you get there." By the way, when we did listen to the ATIS it was six hours old.

It was a fabulous trip that we would recommend to any pilot, not just from a wildlife viewing and tourism standpoint, but also especially from a flying standpoint. It made us keenly aware of how complacent we can become from our routine flying, and how vulnerable we can become when things change. We tend to think we are good pilots, because in our normal flying everything is so easy, with lots of bandwidth left over to maintain situational awareness and mitigate risks.

But in southern Africa we discovered it doesn't take much to lessen that mental bandwidth. The lack of weather information, the unfamiliar geography and airspace, the difficult communications and the unfamiliar risks to consider all served to make us feel very busy.

It showed that, with an unfamiliar airplane or a new type of flying, no matter how much experience we might have we can find ourselves with the reduced bandwidth of a student pilot. The key is to anticipate our reduced capacity when we do new things and leave ourselves plenty of workload margin.

We were reminded of one other thing — learning new things in flying is both challenging and flat-out fun. It is good for the soul.

Get exclusive online content like this delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for our free enewsletter.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox