** | |Illustrations by Chris Gall**|

In Joni Mitchell's 1969 song “Both Sides, Now,” a haunting and sentimental little earwig, the singer laments that after looking at clouds “from both sides now,” she really doesn’t know them very well at all. The same could be said for many pilots. Even after thousands of hours in the air sorting out this kind of visible moisture and that, clouds remain enigmatic. And potentially deadly too, something Joni failed to mention.

Clouds are the dividing line between visual and instrument flight, and, for pilots, they represent a crucible of sorts, a multifaceted challenge with which we must deal before moving on to new levels of experience, capability and opportunity in our flying.

It goes without saying that the pilots least prepared to deal with clouds are new pilots. They not only have the least overall experience but by the time they pick up their private certificate and are turned loose on the airways, they typically have zero experience negotiating clouds. This was true for me when I got my instrument rating.

The end result is, new pilots are forced to deal with extraordinarily complex decision-making processes when they come into conflict with clouds for the first time. Too often, that learning process ends in tragedy.

Every year a couple dozen accidents, most of them fatal, result from pilots inadvertently flying into the clouds. The actual crash at the end of the chain can be caused by one of two things: losing control of the airplane in a catastrophic nature and flying under control into terrain that was obscured by clouds.

The Bad Side

The scenarios are frighteningly common. In the loss-of-control accident chain, the pilot typically lets the airplane overbank. Whether this is through inattention or turbulence, the result is usually the same. In a too-steep bank, the airplane overspeeds, the pilot realizes the error too late, pulls back and overstresses the wings and/or the tail, which fail — end of story.

In the controlled flight into terrain scenario, the pilot does a good to passable job of controlling the airplane when he enters the clouds but a poor job of knowing where the terrain is.

Darkness as well as clouds can precipitate both of these accident types. The common thread is reduced visibility.

Other, less common accidents result from pilots inadvertently flying into clouds. Icing or thunderstorms can cause these. There have been a couple high-profile examples of both of these accident types recently, including a TBM that apparently iced up over New Jersey and a PC-12 that flew into a thunderstorm in Florida. In both cases, the pilots were instrument rated and the cause of the accident seemed to be running into weather conditions that exceeded the aircraft’s capabilities.

Another relatively uncommon accident type is mechanical failure, one that promises to become even less common, as historically the most typical instrument failure that has led to a fatal loss of control in IMC crashes is that of the attitude indicator (or its power source, the vacuum pump). With solid-state attitude sensors and multiple backups common on recent-production airplanes, the likelihood of such a failure is remote.

Most accidents, however, are simply caused by the pilot losing control with no immediate, precipitating cause, i.e., no thunderstorms, no ice, no mechanical failure, nothing that would prompt us to say, “The pilot was simply dealt a bad hand.” In many accidents, the cause is simply reduced visibility en route, a factor instrument pilots at some point early in their journey to IFR proficiency don’t think of as much of a factor at all. When a flight comes to harm with loss of life, it is exceptionally sad to know there likely was nothing other than harmless clouds that lay between a safe arrival and unspeakable tragedy, but very often that is precisely the case.

Regulating Vapor

The problem with clouds is that they are amorphous by nature and so defy easy quantification, and regulations, by their nature, depend on being able to define and pigeonhole the variables. So the FAA regulations regarding clouds — the regs were written many decades ago — are an attempt by the agency to somehow define what clouds are (the easy part: visible moisture) and how we as aviators have to coexist with them (the hard part).

The FAA lays out in laughable detail the distances to keep from clouds to stay legal. In many ways, it’s an academic exercise. For instance, you need to stay 500 feet below clouds in Class E airspace, a requirement that is both useless and impossible to determine and regulate. The controllers, who I assume would bust you for flying 499 feet or closer to a cloud bottom, have no idea where the clouds are, let alone where they are in relationship to you.

From my first days as a pilot, this made me wonder what the purpose was of such regulations. Did they exist, like speed limits for cars, to warn pilots away from operational danger zones? If so, they couldn’t be very effective. Everyone knows speed limits are most effective when drivers believe they stand a high chance of getting a ticket. Cloud limits, however, seem to lack enforceability. Fly too close to clouds — or even right through them — and what is almost certain to happen, legally speaking, is exactly nothing. Where’s the deterrence?

Not only that, but the limits are inadequate. The 500-foot restriction below clouds in controlled airspace is clearly inadequate to protect a jet, for instance, that just descended on an IFR clearance outside of radar coverage. The time it takes to descend 500 feet in a turbojet might be just 15 seconds (30 seconds is my typical descent rate in the Cirrus), and the notion that this is enough time to acquire traffic in a cloudy environment and then take evasive action if necessary is absurd.

Once you start discussing lateral clearance requirements, clearances above the clouds, relative speeds and the infinite number of possible scenarios, the argument will soon descend into Babel-like nonsense.

The sum total, as best I can figure, to the cloud distance requirements is a profoundly complicated way of saying, “stay out of the clouds, especially in controlled airspace, as other airplanes might be in there.”

Even if regulators were able to come up with a sensible matrix of regulations intended to keep airplanes not in the clouds from running into airplanes just coming out of them, there’s another issue: It’s literally impossible to tell how far you are away from clouds. You can mostly tell when you’re in a cloud and when you’re not in one, but figuring out how far you are from one, well, that is a mystical calling. You can sometimes get a rough idea of how big a cloud is, but as you near a cloud formation, that gets increasingly difficult — I’d say impossible. Trying to gauge your distance from a uniquely and infinitely complex, ever-changing object that’s moving too is a fool’s errand. My point, of course, is that this calls further into question the FAA’s regulations about cloud clearances; if you can’t tell how far away the clouds are, and you can’t, how can you obey a complex set of regulations on cloud clearance defined by your distance from the clouds?

Risk

One of the reasons often cited by VFR pilots for why they don’t get an instrument rating is they are worried about the increased risk of flying IFR. (Cost, time and commitment are other big factors.) Is IFR riskier than VFR?

Richard Collins did a study of the subject years ago — one of the few we could find — and discovered that the statistics were clear on the matter: IFR is far safer than VFR when there are clouds around, and VFR with clouds is staggeringly more risky than VFR in the clear.

Like it or not, the takeaway is simply that IFR pilots have a big built-in advantage over VFR pilots when there are clouds around, and VFR pilots greatly minimize their risk by giving clouds a wide margin. Sounds easy, right?

|

Can You Avoid the Clouds?

I fly IFR on just about every cross-country trip I make, a practice I started shortly after I got my instrument ticket in the mid-1990s. At first, like most new instrument pilots, I filed on sunny, VFR days to get the hang of flying the airways, communicating with the controllers and interpreting the instruments. All of that was before moving maps were ubiquitous, so it took a lot of craft to make it come out right, which it usually did.

My biggest impression after doing this for a while, even on days with a benign high overcast or slightly lower broken layer, was that flying IFR made trip planning a lot easier and the execution of the trip a relative piece of cake because I didn’t have to struggle to stay clear of clouds. If one appeared where I hadn’t expected it to be, I’d just fly through it. Nothing could be simpler — not to mention safer.

When you’re VFR, however, it can get really complicated really fast. Here’s a common scenario: You’re a relatively new VFR pilot and you planned a flight from KXYZ to KABC, intending to cruise at 5,500 feet heading eastbound toward the destination. You picked that altitude in order to have adequate terrain clearance over the mountains in that direction, and it worked fine for the planning phase since it also gave you some clearance under the forecast layer. You preflight, taxi, take off and start the climb.

However, shortly after departing on the climb, you realize the layer is lower than forecast, by quite a bit, it seems, and there seem to be multiple layers, the first one looking a lot more like “broken” than “scattered,” as had been forecast. As you continue the climb you realize you can’t make it to 5,500 feet without being partially in that broken/scattered layer — should you try anyway and dodge the clouds you do encounter? Or should you accept a lower altitude? While the odd altitude of 3,500 feet is OK for now, it will give precious little clearance when the mountains start, and there are peaks slightly higher than that, at least you think so, and the clouds seem to be getting a bit lower as you proceed. By the time you’re in the mountains, you’ll be in Class G, so you only need to be clear of clouds, right? As far as terrain is concerned, well, you still have a little while before you need to worry too much about that, right? Once the terrain starts rising, you can climb a bit if need be because you’ll still have adequate clearance over the terrain — at 3,000 feet agl or below you don’t have to comply with the cruise altitude rules, right? — at least you think that’s what the regs say.

If you have any experience, you soon realize you are unwittingly putting yourself into a few different traps. First, you are putting yourself at risk of not being able to maintain terrain clearance under the layer. When that happens, especially if you encounter rising terrain, as on this hypothetical mission, all bets are off.

Avoiding terrain requires only a few hypothetically simple things: knowing where you are laterally, where the terrain is in relationship to you, what the height of the terrain is and what altitude you are maintaining (if, indeed, you can maintain that altitude without entering the clouds). These all sound straightforward, but they are not.

The problem is that once you start trying to avoid the clouds, it’s easy to lose track of where you are in two dimensions over the ground. Before the advent of moving map displays, this is where pilots would get hopelessly lost in faceless terrain flashing by through holes in the clouds. All too often, the next loud sound they heard was their last.

This is the way scud running often happens. It’s not a plan but a reaction to lower weather than forecast, and the flight becomes a tactical one, just trying to stay clear of clouds and terrain for a few more minutes until they start closing in again. You’re too low, too fast and so consumed in what you’re doing you don’t have time to formulate a plan. You start to rely on your instincts, and when you’re a new pilot, the problem is, you haven’t developed many instincts yet. Or, if you have, they might be bad instincts.

Another problem is keeping track of terrain height. While it’s easy to do when you’re on an airway or along the path you drew with a pencil on the sectional while doing your preflight, it’s not easy when you start deviating to avoid the clouds, as often that deviating takes every ounce of attention you have.

The IFR Version

Let’s back up to that departure again and imagine an IFR flight plan — filed for 5,000 feet. You take off and realize the cloud deck is a little lower than forecast. You climb to 5,000 feet, join the airway as cleared and proceed en route, moving in and out of wispy clouds as you go. On that day, that’s as hard as it gets, and you know the altitude you’re flying at will keep you well clear of the rocks below.

While it’s true that thunderstorms and icing can play havoc with what seems a solid IFR plan, the same can be said, and then some, about VFR flight plans. In general, IFR makes the whole process easier and safer.

Experience the Hard Way

If it sounds as though I know what that scary VFR flight is like, you’re right, because I lived it. The scariest event was a flight home to the high desert in Southern California from Scottsdale, Arizona, the second leg in my commercial cross-country, which I’d decided to fly with my older nonpilot brother as a passenger. Though it’s been 30 years, I remember the details quite clearly. If you’ve flown much in the Southwest United States, you know that clear weather is the norm. On that day, however, there were clouds forecast. I was just a teenager working on my commercial certificate and realized the weather looked nice for the flight out but that at some time after I’d be returning, clouds were going to move in and there would be a ceiling.

The trip out took longer than I’d anticipated, the service at the diner was slow, and when we got back to the airplane, it hadn’t been fueled, so that added to the time delay. It was winter, so we had less daylight to work with than usual, and I was getting understandably anxious. One thing was in our favor: It was unseasonably warm, so ice wasn’t a factor.

We took off from Scottsdale, and I managed to get us about three-quarters of the way home before we flew into the high desert and made the turn toward our destination along the high side of the San Bernardino range, over Twentynine Palms, Yucca Valley and westward. As we flew, the ceiling continued to drop. I was just below the bottom of the ceiling, navigating by pilotage, having made a few slight diversions, when I noticed things looked very different from 800 feet agl than they did at 3,000 feet agl. At that point, I made a turn through a shallow sloping pass that followed a road I thought would take us safely home. Very soon, the terrain started to rise precipitously, and I started wondering where I was, though I kept right on going. My brother was the first to speak up, saying he thought we were headed up a mountain road and not along the desert highway we’d both thought we were following.

|

The one smart thing I’d done already was slow down. I slowed even more and carefully made a smooth and level 180-degree turn. I retraced my steps, found the right road and made it home under a low ceiling that I would argue was still VFR.

When we arrived at our home base, I was greeted by my flight instructor and my dad, both of whom were clearly worried about what might have become of us. I never told them the whole story, and it’s possible my dad is learning this story for the first time here.

Training Fail

The saddest part of this risk matrix is we put new pilots in harm’s way by not properly preparing them for the very real challenges clouds can bring, especially when terrain is a part of the mix.

The sad truth is, we do a miserable job of preparing new pilots to deal with the very hard decisions that otherwise-harmless clouds will very likely force upon them on some flight in the near future. After my scary near-disaster, I felt a mix of emotions, the first of which was relief, followed soon by shame that I put myself and my brother in that situation. I felt somehow that I was less of a pilot for making the mistakes that led up to near-disaster. What I didn’t realize was that I was set up to make those mistakes and that any pilot with my experience and training would have performed the same. I should have been proud that I asked for help, listened and then made a really good 180 when I needed to.

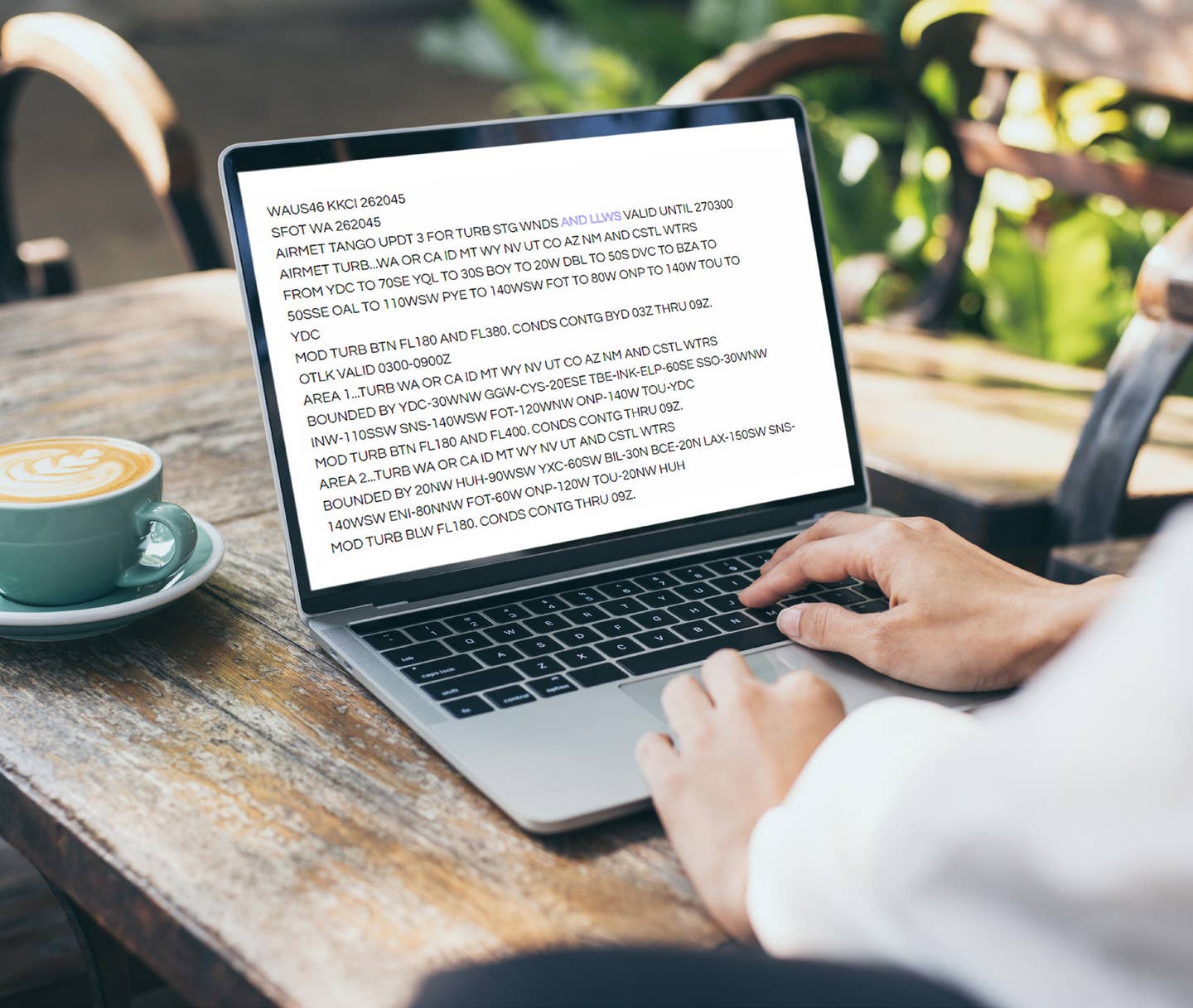

I was in over my head, and this is the case for many new pilots facing clouds. Think about it. As a new pilot, I was expected to be able to gather and translate weather using an arcane teletype language, figuring out in the process what the weather was, what time it was for, what altitudes and areas it regarded and what the special hazards were, all as it applied to a flight that would cross a wide region of the country over treacherous terrain. Then, I was expected to know how to deal with changing weather mixed with rising terrain and growing darkness. Should I, by regulation, have been prepared for all of this? Yes. Is it realistic for us to expect new pilots to have this kind of knowledge? Clearly, it’s not.

What we should do is talk about the risks of clouds very directly, talk about thunderstorms and ice and terrain and loss of control so new pilots know what to expect. We need also to practice these things. The one thing I could have done on my flight was simply land at another airport and call it a day. I should have. I just wasn’t confident enough to divert. I hadn’t done it before, and I didn’t believe that’s what you do when things go south. You land and everything is immediately better.

The other thing we have going for us is technology. I’ve intentionally avoided talking about how new cockpit safety gear could help in these situations, but it can in a dramatic way. Good autopilots are standard equipment on many newer airplanes, so keeping the wings level even with a high workload is easier than ever. With moving maps, situational awareness is easy. Terrain awareness utilities can tell you with a glance where you are in relation to high ground. With tablet computers you can instantly get updated graphical weather via ADS-B or satellite weather. The tablet can also tell you where the nearest good alternate is. Teaching technology is teaching options. We owe it to new pilots to do that.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox

![[PILOT AND SNELLEN CHART PIC]](https://www.flyingmag.com/uploads/2022/11/2022-FlyingMag.com-Native-Advertising-Main-Image--scaled.jpeg?auto=webp&auto=webp&optimize=high&quality=70&width=1440)