The Clandestine Legacy of the Helio Twin Courier

Designed during an era of twin fever, the expeditionary H-500 blended rotary-wing utility and fixed-wing speed.

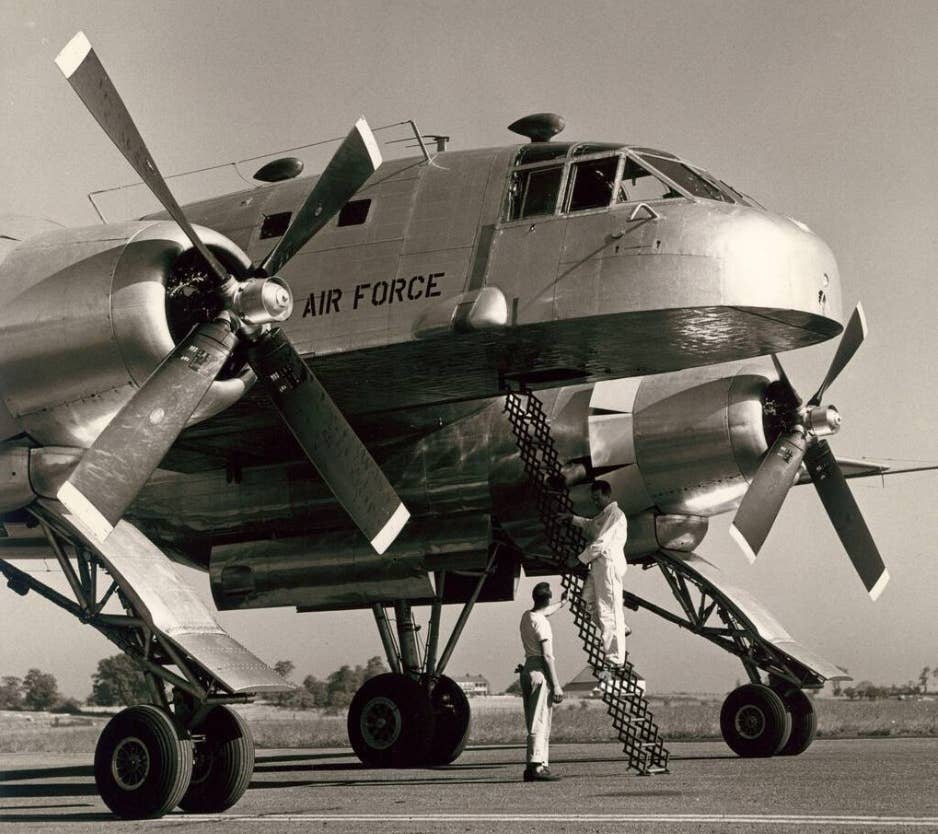

This angle of the Twin Courier shows the extreme forward placement of the main landing gear. While this would have helped to prevent any nose-over tendencies with the high center of gravity, it reportedly made the airplane quite tail heavy. [Credit: Stephen Miller]

During the 1960s and 1970s, many aircraft companies developed twin-engine derivatives of their existing single-engine offerings. Piper produced the Seneca, which was essentially a Twin Cherokee Six. Cessna produced the Skymaster, which could be considered a twin 210. And Grumman created a twin-engine version of the single-engine Tiger called the Cougar.

Whether the demand for twins was a function of a real or perceived lack of engine reliability, or whether it was simply a sign of the industry taking advantage of robust demand for aircraft across all categories is unclear. But what is clear is that aircraft owners and operators had twin fever, and in the rush for market share, even smaller, more specialized companies like Helio responded to the demand and began designing twins.

Starting with their successful short takeoff and landing (STOL) Courier, Helio engineers removed the original engine and placed two 250 hp Lycoming O-540 engines on the wing. With nothing remaining in the nose, they cleverly solved one common challenge among taildraggers—poor forward visibility—by incorporating a helicopter-style bubble window in the nose.

To improve forward visibility even further, they also shrunk the instrument panel, relocating many gauges, switches, and the throttle quadrant to an overhead panel. This had the added benefit of placing engine-related controls and gauges closer to the engines themselves. When combined with the glass nose, the tiny panel afforded pilots outstanding forward visibility.

To maintain the single-engine Courier’s utility in challenging, off-airport operations, they retained the tailwheel configuration as well as the traditional Helio wing design. Utilizing large flaps and slats for better performance at high angles of attack, the wing also incorporated roll control spoilers that deployed with the ailerons to improve roll response at low airspeeds. Helio added a thin, slotted airfoil spanning the two engine nacelles to later models, reportedly to improve boundary layer control over the center section of the wing.

First flight took place in April 1960, and it quickly became evident the engineering worked. Helio touted a 320-foot takeoff distance over a 50-foot obstacle, though it is unclear upon what weight this was predicated. A 1964 evaluation flight by Air Progress, however, reported a takeoff ground run of only 250 feet at a light weight with a 7 mph headwind.

Other performance specs were similarly impressive. The FAA type certificate data sheet lists a single-engine minimum control speed (Vmc) of 59 mph, and Helio claimed a minimum speed of 35.7 mph. Rate of climb with both engines operating was said to be 1,600 fpm, and single-engine rate of climb, 310 fpm. Range was listed as 808 miles.

FAA type certification was awarded June 11, 1963, and Helio gave the Twin Courier a designation of H-500. Foreseeing military use, the U.S. Air Force assigned the designations U-5A and U-5B to the naturally-aspirated and turbocharged versions, respectively. But despite the certification and preparation, only seven examples would ever be produced.

The operational history of these seven aircraft is as unique as their appearance. While Helio publicly stated that all Twin Couriers were delivered to the CIA, they would go on to operate in clandestine operations under various entities of the U.S. military and government. Over their operational lives, some would be given USAF markings, while others would wear civilian paint schemes and civilian registration numbers. The N-numbers were registered to entities speculated to be shell companies for the CIA.

Tracing their operating missions, locations, and agencies is no small feat. Dr. Joe F. Leeker of the University of Texas, Dallas, has compiled what might be the most comprehensive history of the Twin Courier. In it, he traces the progression of each airframe through its respective history, noting that they saw service in Nepal, Bolivia, Peru, and the U.S. before being transferred to—and disappearing in—India. From there, the trail goes cold, and no Twin Couriers are known to exist today.

We can speculate, however. Given the rugged, remote areas in which the aircraft were known to operate, demanding airstrips and conditions likely claimed more than one aircraft. It’s plausible that one or more examples went down in inhospitable terrain and were swallowed by nature and the elements. Others were probably cannibalized for their rare parts. And given their shadowy history, it’s also possible that every trace of the type was intentionally scrapped and concealed from public view.

Considering the clever engineering and intriguing history of the Twin Courier, it’s unfortunate none exist today to be admired in person by future generations. Despite being certified by the FAA, it’s unlikely more will ever be built. In the meantime, we’re left with a small handful of photos, tiny scraps of unclassified U.S. government documentation, and a five-second cameo in the 1965 Jean-Paul Belmondo film, Up to His Ears.

Ultimately, the Twin Courier was an example of the long-standing effort to blend rotary-wing utility and fixed-wing speed, able to operate into and out of tiny, unimproved clearings while still providing relatively brisk cruising speeds. Today, tiltrotors fill the role admirably, but had the Twin Courier been given more of an opportunity to prove itself, it’s possible it would have provided similar functionality in a smaller and considerably less expensive package.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox