The ‘Colossal Mistake’ May Lead to a Colossal Bill

A first-lesson faux pas caused damage, although it wasn’t readily apparent.

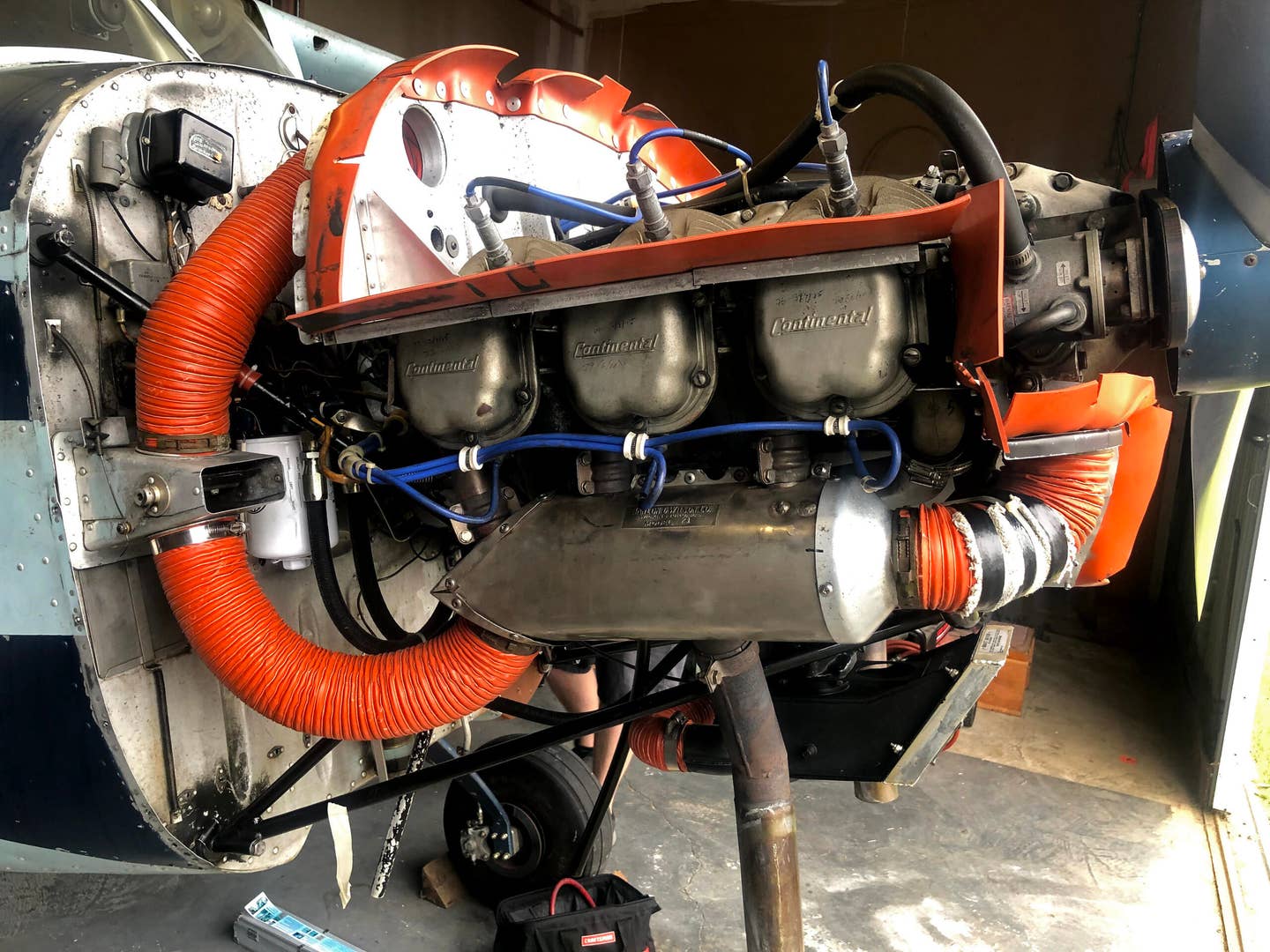

When undergoing routine maintenance, the sight of an uncowled engine is interesting. When undergoing unexpected maintenance, it can be chilling. [Photo: Jason McDowell]

Editor's note: This is part two of a three-part series. You can read the first part here.

One of my favorite writers is an adventure travel writer named Tim Cahill. He has made a career of getting into precarious situations in remote corners of the globe, deftly extricating himself from danger, and then writing about it so we can experience his adventures from the comfort of our living room couches.

Intimately familiar with dangerous animals, sketchy border crossings, and angry men with guns, Tim once observed, “An adventure is never an adventure when it happens. An adventure is simply physical and emotional discomfort recollected in tranquility.” It was this mantra with which I consoled myself as I faced the reality that I might have just ruined my newly purchased airplane.

As described in last week’s column, I made a colossal mistake in my first lesson, mistakenly departing with the cowl plug still in place. The cylinder head temperature had reached a sickening 550 degrees for a few minutes, and we made a precautionary landing at a nearby grass strip. After cooling down, the airplane performed flawlessly for the trip home, so I went ahead and scheduled a second lesson with my instructor for the next day.

Despite there being no obvious signs of damage to the Continental C-145 engine, I drove home from the incident in a pretty depressed state. For nearly seven decades, multiple previous owners had all worked hard to ensure the airplane would be passed on to the airplane’s next caretaker in good condition. I envisioned all of them standing together next to the hangar, slowly shaking their heads in pity and lamenting how the idiotic new owner had just ruined their former pride and joy. I felt wholly undeserving of the airplane for letting them all down.

“Despite there being no obvious signs of damage to the Continental C-145 engine, I drove home from the incident in a pretty depressed state.”

The following morning, I checked the forecast. It had changed, and the winds were now expected to be quite strong and gusty. I generally hold a fairly low opinion of my own skill and proficiency, and as this would be only the second lesson in my new airplane, I phoned my instructor to cancel. I reasoned that initial lessons should be conducted in calm winds, and that I’d feel much more comfortable working up to such conditions rather than diving right in.

My instructor disagreed. He contended that it would be beneficial to get out of my comfort zone, and reasoned that the best time to do so is with an instructor at your side. I grudgingly acknowledged his logic, and after some back and forth, I finally agreed to go ahead with the lesson.

As it turned out, he was entirely correct. Though I was pretty intimidated by the wickedly gusty winds, I fought through and wrangled the airplane reasonably well. On the last landing of the day, a wild gust struck as I was in my flare, about 3 feet off the ground. I rode it out and set it down nicely without any porpoising or bouncing, and my instructor’s loud cheer capped the lesson off nicely.

Throughout the lesson, the engine had performed flawlessly. Cylinder head temperatures were stable and normal, and there was no discernable reduction in power after the previous day’s cowl plug incident. Still, I wondered whether there was any internal damage hidden from view and in an abundance of caution, I decided to seek out a mechanic to perform a thorough inspection.

As the old saying goes, “Small hinges swing big doors.” Similarly, brief introductions spark valuable relationships. I recalled meeting a local corporate jet mechanic a few months prior. In our 90-second conversation, he mentioned in passing that he spent many years rebuilding piston engines at the most highly regarded engine shop in the region. I decided to give him a call.

His name was Dave. He was local, and after hearing about my concerns about potential damage to my engine, he agreed to perform a compression check and borescope inspection for a reasonable price. We set up a time and met up at the airplane the following week.

Though he had been maintaining corporate jets for the previous decade or so, Dave evidently hadn’t lost much proficiency when it came to piston-powered GA aircraft. He quickly removed the cowl and dove right in, first checking the compressions. This was the first bit of bad news—the compressions were notably reduced from when they were checked a few months prior as part of the prepurchase inspection.

Dave explained that the rings had probably been affected by the high cylinder head temperatures, and were the most likely reason for the low compressions. At this point in the inspection, it appeared that all the rings would have to be replaced. I held out hope that the problems would end there, and we moved on to the borescope inspection.

I watched over Dave’s shoulder as he inserted the camera probe into each cylinder and prodded around for a closer look. The camera view was displayed on a handheld monitor, and we were able to have a clear look at the inner workings of the engine. He provided a guided tour, pointing out various items like valves, spark plugs…and cracks.

Sure enough, there were small cracks in three of the cylinders, up by the valve seats. They were small, but they were there. We located another crack near the threads of a spark plug. Dave explained that because of their locations, the internal cracks would most likely be impossible to repair—new cylinders were the only option.

Dave wrapped up the inspection, apologized for the bad news, and headed home. I tidied up, got into my car, and sat there for a while, assessing the situation in silence. New cylinders were around $1,100 each. At a minimum, I’d need to replace three of them, as well as all the rings in the engine. With labor, my stupid mistake was shaping up to cost nearly $5,000.

Later, I reached out to some trusted friends for advice. More than one suggested replacing all six cylinders to be safe, reasoning that if three of them had visible cracks, there was a good chance the other three were also in less-than-perfect shape. That would bring the total cost up around $8,000—not too far away from the cost of an entire used engine.

A look at the usual classified sites online revealed very few used engines available. The handful that were listed for sale had suffered prop strikes or were well past due for a full overhaul. A call to the aforementioned highly regarded engine shop revealed that a full overhaul of the engine, with engine removal and reinstallation, would amount to $35,000—nearly what I paid for the airplane itself. Other engine shops were less expensive, but certainly not cheap.

I was beginning to think that my new airplane would most likely have to sit in storage for the next six to 12 months while I saved money. I’d planned to build and maintain a healthy maintenance fund for instances like this, but my aviation account was nearly depleted after the purchase of the airplane. Things looked bleak.

Thinking back to Tim Cahill’s quote, I reminded myself that today’s physical and psychological discomfort will someday be looked back upon as adventure. As I was recalibrating myself to view the entire ordeal as one part of the grand adventure of ownership, my phone rang. It was my instructor, Pete.

He was calling to inform me that he vaguely remembered something about Dan, the nice gentleman who drove out to check on us after our precautionary landing the previous day. Dan used to have a 170 of his own, and Pete seemed to recall that he might still have a 170 engine sitting in a crate. Pete had no idea about its condition or whether the engine was even still there, but he recommended giving Dan a call.

I decided to do just that.

Next week: Jason McDowell continues this story.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox