The Short, Unconventional Life of the Curtiss XP-55 Ascender

Unlike more traditional aircraft of the time, the XP-55 design mounted a 1,275 hp Allison V-12 powerplant behind the pilot.

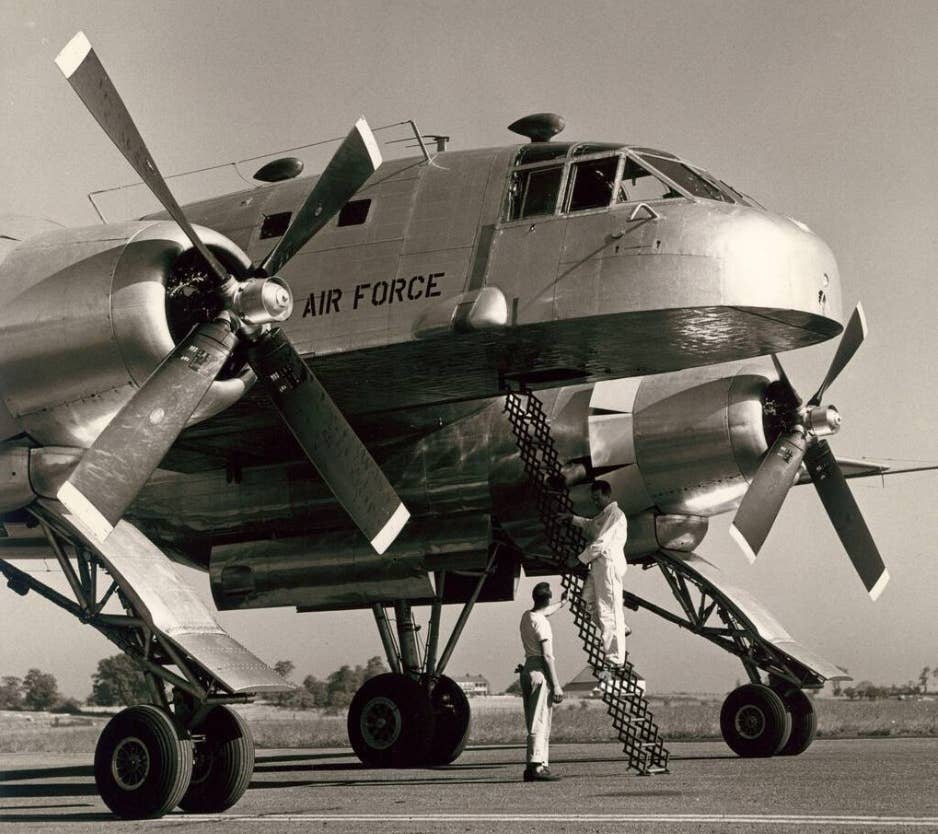

The sole remaining Curtiss XP-55, on display at the Air Zoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan. [Credit: Jason McDowell]

In the world of aircraft design, the late 1930s and early 1940s were defined by rapidly-expanding technologies and open minds with which to pursue them. Tricycle landing gear had recently surfaced, and retractable landing gear enjoyed new popularity. All-metal airframe construction quickly gained traction as well, replacing fabric coverings.

As aircraft designs advanced, engineers pushed the limits ever further. In late 1939, when the Army requested a new fighter that performed better than any existing fighter at a lower price, the Curtiss engineers indeed challenged convention. They responded to the Army proposal with a swept-wing canard, powered by a 1,275 hp Allison V-12 as found in P-38s, P-40s, and P-51s. Unlike these more conventional aircraft, however, the XP-55 design mounted it behind the pilot and drove an aft-mounted pusher propeller.

Curtiss reasoned that the XP-55 would provide many benefits over traditional designs. They claimed the unusual configuration would achieve equal or better speeds, better maneuverability, and superior outward visibility. They also touted design aspects that would make the XP-55 a safer aircraft for the pilot, including the superior ground handling characteristics afforded by the tricycle gear and engine placement that would help protect the pilot from engine fires.

One unique safety-related feature was a jettison system for the propeller. In the event the pilot was forced to bail out, they could first pull a lever that would detach the propeller entirely. The propeller would depart the aircraft, thus providing a clear exit path for the jumping pilot.

The Army awarded Curtiss the contract, and Curtiss proceeded with building a flying testbed to test flight characteristics. Designated the CW-24B, it utilized a diminutive Menasco C6S-5 Super Buccaneer 6-cylinder inline engine that produced 275 horsepower—1,000 less than the XP-55. Because of the lower power rating, Curtiss engineers reduced weight wherever possible, utilizing a fabric-covered steel tube fuselage and fixed landing gear that occasionally sported wheel pants.

Although the CW-24B could reportedly only attain 180 mph, it sufficed for testing purposes and produced valuable data. As a result of 169 flights between December 1941 and May 1942, engineers determined the need for various aerodynamic modifications. They increased the wingspan, added larger vertical stabilizers to the wingtips, and added dorsal and ventral fins to the engine cowl—all to improve stability and controllability.

The first of three XP-55s made its maiden flight in July 1943, only to reveal significant controllability issues that the CW-24B failed to uncover. In addition to insufficient pitch authority on takeoff, the first prototype struggled with inflight stability—so much so that when a test pilot entered a stall, the aircraft flipped over and entered an unrecoverable, inverted descent. The pilot managed to bail out, but the first prototype was destroyed.

Curtiss proceeded to build and fly the second and third prototypes, and testing continued. Despite significant efforts to address the aircraft’s deficiencies such as poor stall recovery, insufficient engine cooling, and performance that remained inferior to existing, conventional designs, these issues would remain unsolved. In addition, the jet-powered Bell P-59 Airacomet had, by this time, been flying for nearly two years, and it was becoming clear that jets would replace propeller-driven fighter aircraft. The XP-55 program was, therefore, discontinued.

In 1945, the third XP-55 was chosen to fly in an airshow held in Dayton, Ohio. Tragically, while performing a roll in front of the crowd, the aircraft dove into the ground, killing the pilot and leaving the second prototype as the sole remaining example of the type. Today, that XP-55 is on display at the Air Zoo aviation museum in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox