The Unconventional, Bizarre Bell Airacuda

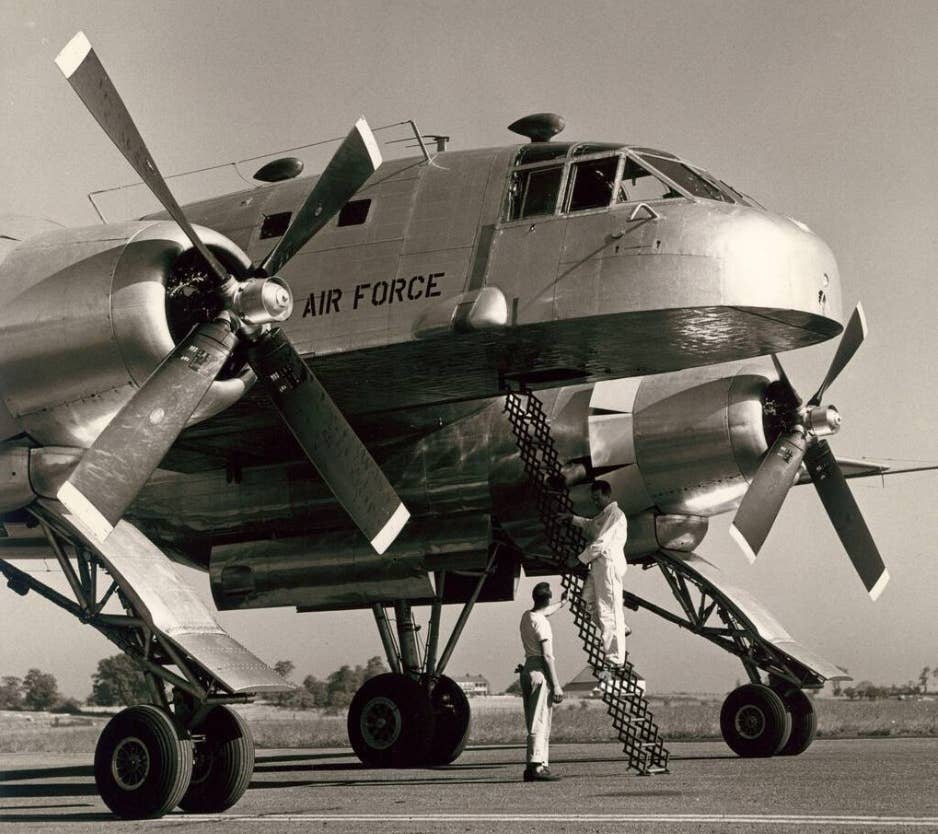

The Bell YFM-1 long-range and heavily armed escort fighter featured twin pusher engines housed in glazed nacelles.

An Airacuda in flight, with vacant nacelle seats and the second control yoke in the stowed position. [Credit: U.S. Army Air Forces]

Larry Bell, founder of the Bell Aircraft Corp., now known as Bell Helicopter, entered the aircraft manufacturing industry with a unique bang. After dropping out of high school in 1912, Bell worked for various aircraft companies, including Martin and Consolidated, before starting his own company in 1935. Rather than beginning with a conservative, basic aircraft type, he opted to respond to a military contract by proposing one that was so unconventional it bordered on bizarre.

That aircraft was the Bell YFM-1 Airacuda, a long-range and heavily armed escort fighter designed as an interceptor and bomber escort. It was part of a newly emerging category of aircraft containing models described by FLYING in 1941 as “virtually impregnable fortresses of themselves, yet maintaining considerable maneuverability and striking prowess which the big bombers lack.”

The design and configuration of the Airacuda was like nothing the industry had ever seen. The twin pusher engines were housed in glazed nacelles, each of which contained a crewmember, for a total of five. And while most of the 15 examples built were taildraggers, three incorporated tricycle gear—a cutting-edge aircraft development at the time.

In the fuselage, the pilot was accompanied by two other crewmembers. Seated in close proximity was an individual who handled three duties—copilot, navigator, and fire control officer. This multitasking expert was provided with a stowable control column and pedals to help fly the aircraft and was typically the one in charge of aiming and firing the various gyro-stabilized cannons and machine guns bristling from the airplane. In the back, a third crewmember handled radio communications and manned .50-caliber machine guns mounted in side pods to protect the aircraft from aggressors approaching from the rear.

Out in the engine nacelles, the remaining two crewmembers had somewhat simpler tasks. While they had the ability to aim and fire the .30-caliber machine guns in their respective nacelles, their usual duty was simply to reload them. Of somewhat more significant concern was what they would do in the event they had to bail out and fall through the path of the propellers churning the air immediately behind. While various sources refer to explosive bolts intended to jettison the propeller blades prior to bailout, the flight manual only refers to an emergency feathering procedure in which the electric props would feather and stop in six to eight potentially very long seconds.

Almost immediately upon making its first flight in September 1939, it became clear the Airacuda engineers had perhaps bitten off a bit more than they—and the flight crews—could chew. With 1,150 hp Allison V-1710 V-12 engines, the 21,625-pound aircraft could achieve 268 mph in high-speed cruise and reach a service ceiling of 29,900 feet. However, the flight control characteristics and single-engine handling were atrocious and would now be considered far too dangerous to approve for production.

The flight manual made no attempt to hide the unforgiving handling characteristics from pilots, warning that “due to close proximity of propeller to tall surfaces, a sudden reduction of power of one engine either through an engine failure or excessive movement of one throttle will result in a much more violent and immediate control reaction than on multiengine, tractor-type airplanes. Failure of one engine may result in a spin unless the other engine is retarded or trim tab control adjusted immediately.”

It went on to include some concerning limitations: “In case of failure of one engine the other engine should be retarded immediately and the throttle of [the] good engine advanced gradually as trim tab control is adjusted to counteract turning moment. With proper adjustment of [the] trim tab, airplanes can be safely flown on one engine. Single-engine practice flights will not be engaged in below [10,000] feet. This airplane should be flown only by experienced multiengine pilots.”

To provide sufficient electrical power for the various power-hungry systems, such as the targeting gyros, Bell designed the airplane around a 13.5 hp, 2-cylinder, four-cycle piston auxiliary power unit (APU) mounted in its forward belly. It ran at a constant speed of 4,000 rpm and powered the majority of systems, including the aforementioned propellers. Contrary to many reports, the APU was, in fact, not the sole source of electrical power—the right side engine was fitted with a backup generator to provide emergency electrical power to the aircraft in the event the APU failed.

Compounding the challenges of the Airacuda’s unconventional design was insufficient engine cooling. When idling on the ground for extended periods, the aircraft required special fan units with custom ducts that fed into the wing leading-edge intakes to prevent the engines from overheating. This also led to some operational difficulties in flight.

Ultimately, no further examples of the Airacuda would be manufactured, as the combination of long-range bombers, such as the B-17, and traditional fighter escorts, such as the P-51, proved effective in the war. Two Airacudas were lost in accidents, and unfortunately, all remaining examples were scrapped by 1942.

While the small fleet never directly contributed to the war effort, Bell learned valuable lessons from its design, testing, and production. To keep the engines positioned forward, for example, and thus maintaining a proper center of gravity, each Airacuda engine incorporated a 64-inch driveshaft extension. The vibration and harmonics involved in such an extension are not trivial, and this experience likely helped refine similar extensions utilized in the later P-39 Airacobra and P-63 Kingcobra, both of which were manufactured in the thousands.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox