Getting Back in the Seat? Here’s How to Get Your Flying Skills Up to Speed

There are plenty of things to brush up on if you haven’t flown in a while. [File Photo: Adobe Stock]

Editor’s note: This article is the fifth in a six-part series examining the aviation industry’s pilot shortage and what can be done about it.

Jan. 14: An overview of the issue | Jan. 17: How the military is dealing with its shortage | Jan. 18: Recruiting right from the flight schools | Jan. 19: Outreach programs doing their part | Jan 20: The role of flight schools in creating pilots | Jan 21: Want to get your chops back? Here’s how.

Are you one of those pilots who earned their certificate and made it a point to fly at least three times a month, and then—dramatic pause—life got in the way? It's a big club, my friend. Work, family life, financial challenges, all these things can pile up until you realize that it’s been months or even years since you exercised those hard-earned pilot-in-command privileges.

The good news is, you don't have to repeat all the training to regain your flying mojo. Once those hours are recorded in your logbook, they’re there to stay. You do, however, need to demonstrate a certain level of skill and proficiency to regain flying privileges.

For most pilots, regaining currency begins with dual instruction. Leave your ego at home for this.

There is a saying: be humble in aviation or else aviation will humble you. Nowhere does that manifest more prominently than in the cockpit for the pilot who seeks to return to flying after a hiatus.

“There is a saying: be humble in aviation or else aviation will humble you.”

It doesn't matter if you earned your pilot certificate (insert impressive number) years ago and have (insert even more impressive number) of hours in your logbook, or have flown (insert names of challenging airplanes, approaches, and destinations). Regaining pilot currency and proficiency will likely be a challenge. Check yourself for macho, anti-authority, and invulnerability attitudes when you show up at the flight school.

FAA Rules

FAR 61.56 states that in order to exercise pilot-in-command privileges of an aircraft, every 24 calendar months the PIC must accomplish a flight review that consists of a minimum of one hour of flight training and one hour of ground training. (There are a few ways around this, such as

adding an additional certificate or rating to reset the clock, so to speak, or participating in the FAA's Wings Program). The flight review consists of the current general operating and flight rules per Part 91 and flight maneuvers that at the discretion of the person giving the review are necessary for the pilot to demonstrate the safe exercise of privileges of their certificate.

If it has been more than two years since you flew, the flight review will probably take longer than one-and-one. The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), which has done extensive research on helping rusty pilots return to flying, has noted that for every year the pilot was out of the cockpit it takes about 45 minutes to one hour of dual instruction to regain flying skills. You may want to think of the dual training as the mother of all flight reviews. You are flying until you demonstrate a certain level of proficiency as set forth in the airman certification standards for the level of certificate that you hold.

What to Expect

If you are a flight instructor and have never administered a flight review before, check out Advisory Circular 61-98D covering flight reviews. While not regulatory in nature, the AC offers guidance on what items should be covered during the review. The CFI and pilot seeking to return to the cockpit should create a plan for the review, noting the performance metrics in the Airman Certification Standards so that there are clear expectations before the review begins.

Be ready to offer up a metric when you are asked: “How long has it been since you acted as pilot in command? Has it been more than two years? 10? 20?”

“A while” and “a really long time” are not an answer, anymore than “looks pretty good” is a PIREP. The length of hiatus is important because some rules may have changed since you last flew—is there more controlled airspace where you are? Did the airport have VFR departure procedures? When the CFI learns how long it’s been since you flew, he or she can better tailor the training experience.

Some even ask the CFI for specific training, such as night flying or cross-country flight planning and execution, because they have a trip in mind, and they want to be sure their flying chops are up to standard.

Remember, the ACS represents the minimum standards for certification. Be gentle with yourself as you get the rust off your certificate. It didn't get there overnight, so it won't disappear overnight. Take your time.

The Common Soft Spots

Muscle memory—no matter what skill you are dusting off—usually comes back quicker than knowledge. Remembering FARs, airspace, and aircraft systems often takes a bit more effort. It behooves you to study the sectional, the FARs, and the pilot's operating handbook or Airplane Flying Handbook before you show up for the review. Read over the procedures for engine start and emergencies, use the checklist, and once in the aircraft, be prepared to make radio calls.

Bring a current copy of the FAR/AIM to the session—and have it tabbed to the pertinent subjects such as weather, FARs for pilots, Part 91 airspace, and so forth. A good CFI will turn these knowledge soft spots into a teachable moment, allowing you to find the information with a minimum of coaching— because a big part of being a pilot is knowing where to look for information.

Study the VFR sectional ahead of time, referring to the legend to verify symbology. Note the floor and ceiling of the controlled airspace near you, and refer to Chapter 3 of the AIM if you have questions. Just because you do not routinely fly into and out of a particular airspace does not relieve you of the responsibility for knowing about it.

The "I don't fly there" argument comes from two camps: the pilots who trained at towered airports and are intimidated by pilot-controlled, non-towered fields, or the pilots who trained at non-towered airports and are put off by having to talk to the tower.

To the CFIs who are reading this: suggest to the client that part of a flight review is getting out of their comfort zone, which may mean going to a towered/non-towered airport with the help of the CFI. Create a scenario, such as a disabled aircraft has closed the pilot's home airport and the only safe course of action is to divert to a particular field.

The ‘Just’ Factor

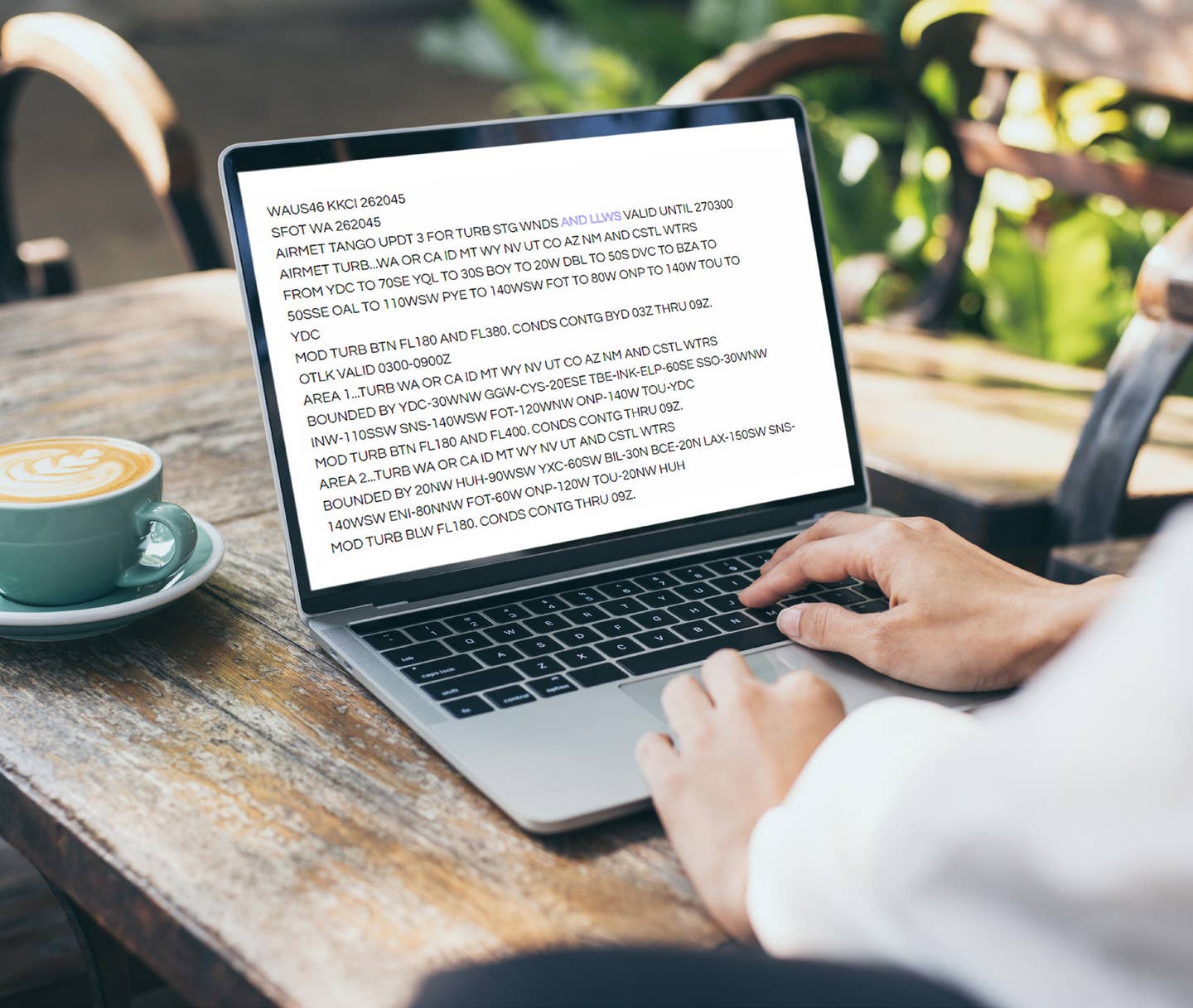

Weather, specifically obtaining a weather briefing and interpreting the weather, is another area that can be a challenge, as many pilots “just fly on good days.” Chapter 7 of the AIM is a great resource for weather knowledge, and there are details on the symbology and abbreviations found in weather reports. There is even a page on giving a weather PIREP, which can help you craft a better response than the non-informative “looks pretty good.”

Weather is often a factor in aviation accidents and incidents. Put in the time to learn to obtain and interpret weather briefings so you do not become a statistic. This is more than being able to read a TAF and METAR—you should understand the causes of weather where you are flying. For example, when the winds come from the east over the mountains, anticipate turbulence and snow; when the winds come from the north and pass over the lake, lake effect snow may be a possibility.

The ability to calculate weight and balance also tend to wane when not used on a regular basis. The "it's just me" or "just me and (insert name of favorite passenger) in the airplane" excuse has bitten many a pilot who accidentally overloaded their airplane.

Determining aircraft performance is another skill that can quickly fade. Ideally, performance should be calculated before every flight. How much runway are you going to require on takeoff? If you do not calculate this, how will you know when the aircraft is not performing adequately?

Takeoff calculations are particularly poignant when density altitude is present, as the pilot may fail to recognize a density altitude situation and the corresponding poor aircraft performance. This can be deadly when the pilot runs out of runway and options at the same time. Pilots learn that high field elevation, high temperatures, and high humidity result in density altitude, but some do not realize that it only takes one of these three things to create density altitude. You can have density altitude at sea level on a hot day. Be conservative with the performance numbers in the POH, as they were likely based on a brand-new airplane with a test pilot at the controls.

Getting Back in the Cockpit

Once you have regained flying privileges, try to build time in your life for both flight and aviation study. Aim to fly at least once a month and do an online course or watch a training video once a month (or more) to keep your knowledge fresh. You might also try to find an aviation club and/or organization that encourages their members to stay current and proficient.

Above all else, enjoy the time in the sky!

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox

![[PILOT AND SNELLEN CHART PIC]](https://www.flyingmag.com/uploads/2022/11/2022-FlyingMag.com-Native-Advertising-Main-Image--scaled.jpeg?auto=webp&auto=webp&optimize=high&quality=70&width=1440)