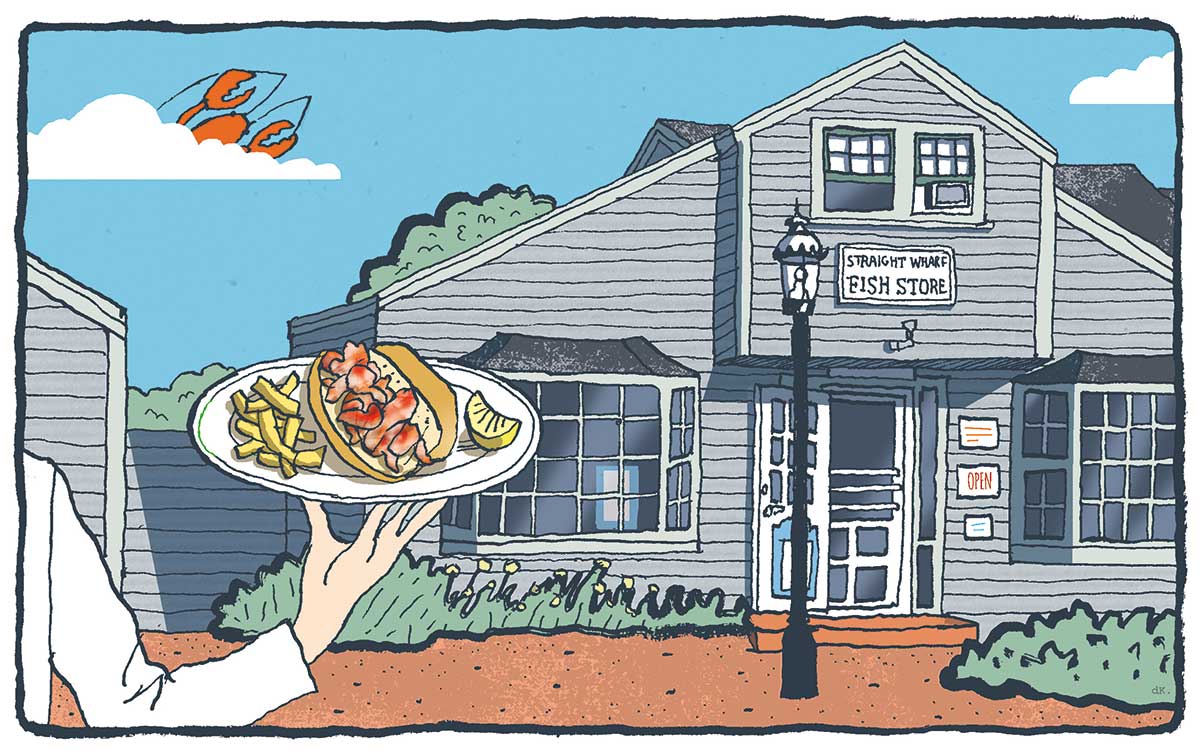

Straight Wharf Fish Store Illustration by Philippe de Kemmeter

The airplane looked absolutely the same. It was the same Piper Arrow II with the blue-and-silver accent ribbon that flowed from the tail to the nose against a white background. It was the same airplane that was displayed on almost 200 hours of my logbook pages. I smiled knowing that my former career as an airline pilot had paid for the shiny paint scheme.

So, what was different? A simple realization: The airplane would now be the only one I would fly. And I would fly the Arrow not because my livelihood depended on it, but for the simple pleasure of operating it.

Approaching the airplane from the ramp, my mind momentarily flashed to the intricate cockpit of the Boeing 777. I remembered embracing the pure enjoyment of knowing the difference between the operational norms of my professional flying and my general aviation flying. The fact that they were once an integral part of my life afforded me the opportunity to appreciate both. And that opportunity still existed except for the fact that one airplane would soon become a fond and distant memory.

It was the first time the realization began to resonate. I wasn’t depressed by any stretch. As a matter of fact, the thought was pleasing. No uniform. No review of a flight plan in the form of a milelong computer printout. No TSA. No Customs. No long hours of boredom across a vast ocean. No backside-of-the-clock fatigue. No schedule. What wasn’t there to like?

As I plopped down into the pilot’s seat, a new revelation reached my psyche. I had become that retired airline guy flying a GA airplane. Would people think of me as a “been-there-done-that” kind of pilot with thousands of hours who knew it all?

Or would I be considered an overqualified pro who has only fractional knowledge of flying small airplanes? Or perhaps others would assume that I was one of those overconfident airline pilots with a cavalier attitude.

Honestly, it didn’t really matter how I was perceived, only that my operating practices followed good judgment and safe procedures for those who thought enough of my abilities to be passengers. That being said, despite the usual good-natured ribbing because of my airline background, I would still be setting an example. Reckless and cavalier could not be part of my repertoire.

After I scanned the instrument panel and began my practiced flow of checking switch positions and displays, I began to slide out of the airplane. But I paused for a moment. How about stepping up the game and being a little bit more methodical?

After all, my proficiency would no longer be reinforced through professional flying. I grabbed the checklist card out of the side pocket and carefully read, ensuring all the items of cockpit preparation had been accomplished. It wasn’t that a checklist was foreign to my procedures, it was just that I realized familiarity with a piece of machinery to which one is the sole operator sometimes lends itself to complacency.

But maybe I was taking myself too seriously. My departure would only be for a solo lunch flight, mostly to exercise the airplane after a month or more of inactivity, to an airport 35 minutes away. What could possibly go wrong as a result of an inadequate preflight?

Progressing through start, run-up and taxi, I realized that my fluency of motion was a bit rusty. My fingers moved about the cockpit displays and switches with an occasional hesitancy. Even my communication with ATC was slightly erratic as I uttered a sentence or two of non-standard phraseology. Was I already transforming into the retired-airline-pilot weekend warrior?

Despite my deficiencies, I managed to safely navigate the airways, locating the airport and the airport restaurant. It was a pleasant lunch mission. Knowing that I would have the freedom and flexibility for similar missions made the flight even more enjoyable. On that subject, for a month or two, the thought of lobster sandwiches at my favorite behind-the-scenes seafood shop in Nantucket became a background obsession.

I infected my wife with the thought. It would be a welcome break from the process of preparing our Connecticut home for sale. When a beautiful, clear blue VFR day arrived in the middle of the week, off we flew. The combination of our own airplane, a Nantucket destination and a lobster sandwich seemed to me the epitome of aviation opulence. It didn’t get much better.

But alas, the airplane had a mind of its own. Shortly after takeoff, the Aspen system began to offer a goofy display of various parameters. The electronic PFD was becoming a jumbled pixilation of colors. Apparently, it was time to test the retired airline guy. No copilot to consult. No dispatch to contact. Abort the mission or continue? “Fly the airplane first, Mr. Professional,” I chided myself.

Through a combination of the errant Aspen display and the analog steam gauges, I managed to keep the blue side in the appropriate position while maintaining my best game face for the benefit of my wife. Within short order, I deemed the situation a non-event, especially in our severe VFR environment. All the primary flight instruments were available and the Garmin 430 offered us the opportunity to navigate via GPS, notwithstanding the old-fashioned VOR thingies. Our lobsters would still be quivering. Progressing toward Long Island Sound, test No. 2 began in the form of a reoccurring problem with which my mechanic buddy and I have become intimately familiar.

The amber gear-in-transit light illuminated. As per what had become my standard procedure, I glanced immediately at the ammeter gauge to confirm that the electrical load was normal, verifying that the hydraulic-power pack for the gear wasn’t activating. To spare you the intimate details of this ongoing annoyance, suffice it to say that as simple as the Arrow’s system is, the micro-switches and adjustments on the gear can be finicky. Regardless, the influence of my former professional life doesn’t allow me the luxury to stare at any type of warning light without squirming even if I diagnose the problem as a nonissue.

The above being said, I elected once again to continue with the mission. After all, even if gear extension proved to be a problem, we would have to land somewhere. And the proof of gear operation would ultimately be three green lights, whether the in-transit light was dark or remained illuminated … which it wouldn’t. Confident that I had a 99.9 percent chance of success, why not fly toward our awaiting lobsters?

My final challenge was much less dramatic. The iPad program linked to my GTX-345 ADS-B transponder was not providing FIS information for traffic and weather no matter how hard I mashed the appropriate selections. A switch to the Garmin Pilot app brought our electronic data reception back to normal. I wiped my brow.

At the end of a very pleasant day with my wife and our airplane, lunch was a complete success. Except for my flying proficiency in regard to landing, the return flight was flawless. I’m thinking that the old, retired guy can still do this.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox