Martha Lunken tries to get to the bottom of why an experienced pilot fatally crashed a Cirrus SR22. Jim Koepnick

I’d just sunk my hands into a gloriously gluey lump of flour and water when the wall phone rang. Yes, I still have a landline, bake bread, can pickles, put up preserves and make mud pies. I grabbed the receiver with my grossly sticky hand and spent most of a half-hour listening to a young student pilot who wanted advice about her attempts to get an FAA medical. Because of those years on the dark side I guess people think I have the inside scoop on medicals, violations, accidents, airplane certifications and unscrupulous mechanics. While that’s rarely true, I can often come up with a suggestion or point them in some direction. But this lady’s situation was as sticky as the wad of sourdough I was kneading.

It was a textbook example of finding yourself in a world of hurt with the FAA’s online MedXPress process. I can’t say often enough that you should consider any condition, syndrome, diagnosis, surgical procedure or prescription medication — something as seemingly benign as allergies, childhood asthma, ear infections or sleep apnea — that might raise a red flag before hitting “send” on your application. If you’re at all unsure, schedule a consultation with a good aviation medical examiner (AME). The cost of an extra pre-medical office visit could save you time, money and grief if something might be disqualifying or require review and a special issuance. The grapevine or the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association is the best way to find a “pilot advocate” AME in your area. AMEs can OK some medications and conditions on that form, but others have to be referred to the FAA for review.

This lady’s situation was gnarly because her MedXPress application was in the system and she had taken the exam with some serious issues that no AME could defer. The AME’s only option was to send it on to the FAA for review and, hopefully, a special issuance. The FAA denied the request, advising that she could appeal the decision, and she wanted me to recommend a “more cooperative” AME. The AME wasn’t the problem, and doctor shopping at this point wasn’t an option.

Knowing of similar cases, I told her she could try, but the time and expense of the required tests and procedures were usually prohibitive and ultimately fruitless.

She had taken nearly 100 hours of dual and was absolutely devoted to her instructor, which was, I think, the real reason for her call because he’d been killed earlier that week on an approach into his home airport.

I hadn’t heard about the accident, but I recognized the name because, a few months before, I’d given him a rather unusual practical test; he held a multiengine ATP but wanted to remove the “commercial privileges single engine land” limitation on his certificate, so we flew a Cessna 172. He had several thousand hours of military helicopter and fixed-wing experience and was currently picking up odd flying jobs and instructing.

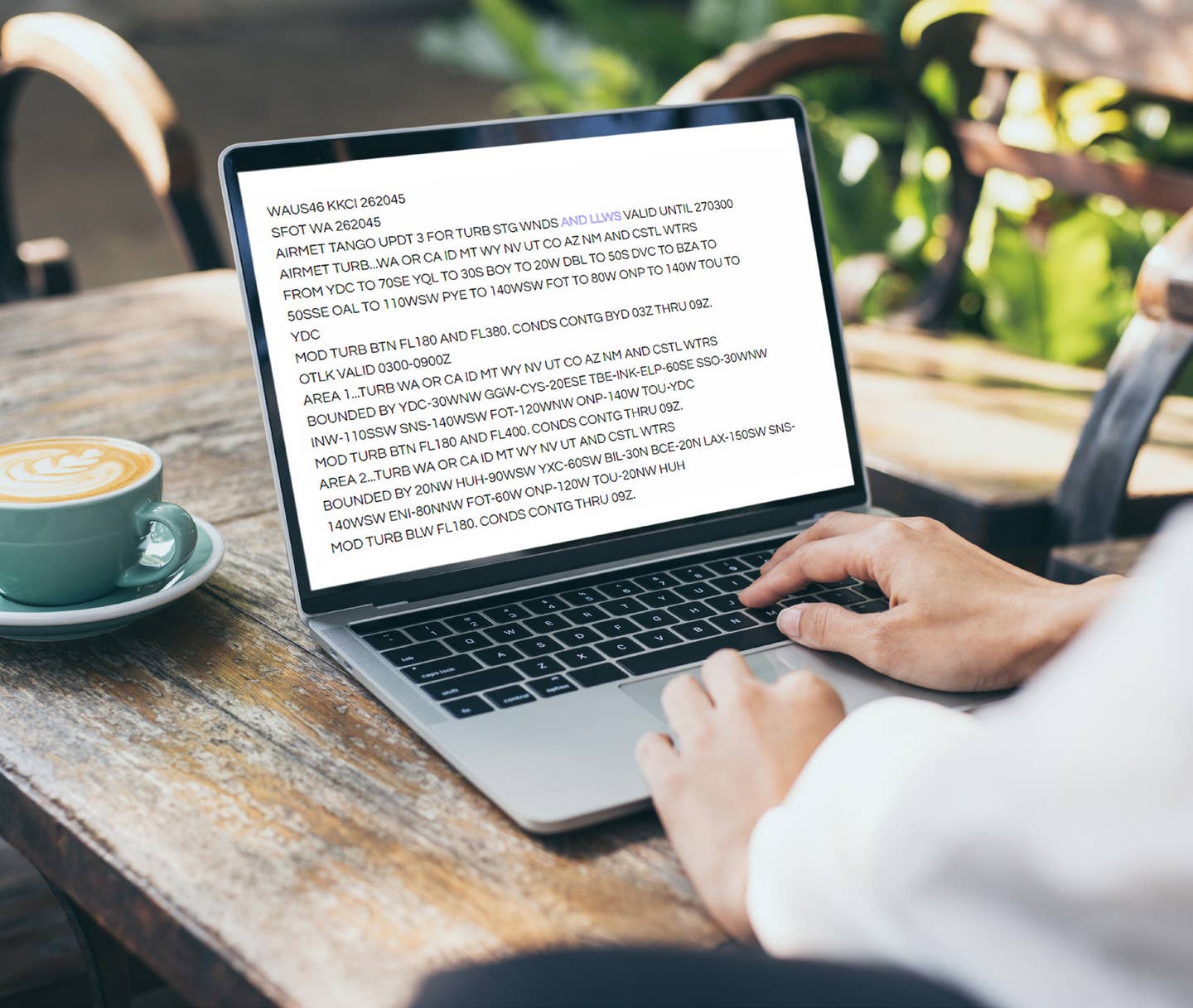

The accident happened when he was bringing a Cirrus SR22 back to his home airport near Dayton, Ohio — a 100-mile flight he’d made many times in this same airplane. He’d filed IFR but broke out of the cloud base with good visibility and was circling to land on Runway 25 with a strong, gusty west wind. The lady told me the airplane had been in maintenance and “they” had determined the cause of the crash was fuel-pump failure.

That sounded a little odd, so I dug into it and read statements from a number of pilot and nonaviator witnesses who said the airplane had approached the field going very fast, was very low and had made an unusually steep turn onto final.

It didn’t seem rash to suspect a classic stall-spin event, and in fact, the NTSB preliminary report stated: “The aircraft apparently experienced a stall-spin and subsequent impact with airport terrain … [with] one fatal injury.”

This has been happening since Orv and Wil flew out of nearby Huffman Prairie. I have an early World War II training film with Clark Gable in the role of an angel welcoming young pilots at the Pearly Gates — guys who stalled and spun AT-6 trainers turning onto final. And, yes, the Cirrus has seen its share.

I am not saying airplane design was a factor in this accident and don’t want to — again — piss off the people in Duluth, Minnesota, who build this marvelous machine. In a column I wrote about practical tests with pilots who learned to fly in Cirrus airplanes, I said I didn’t (and still don’t) think the Cirrus makes a good basic trainer. The school where I hang out is a Cirrus training and service center, and I was amazed and amused when Cirrus told the owner to remove my name and picture from the school’s website. There’s no doubt if I stalled my Cub in a turn to final at 250 feet agl with the controls crossed that I’d make a hole approximately the same size in the ground. But I’m convinced that pilots who learn to fly from the get-go in “technically advanced” airplanes rarely understand or develop the art of airmanship and often aren’t aware when they get too close to the edge.

The Cirrus is challenging to hand-fly because it wasn’t designed to hand-fly. The sidestick is sensitive, and the amount of stick travel, even for large pitch changes, is minimal. It’s amazingly efficient and fast, and that emergency chute has saved lots of lives, but that ballistic parachute is useless if the airplane stalls and spins out of a maneuver at 300 feet.

But I’m bothered because this pilot didn’t fit that mold. He had plenty of experience in lots of flying machines and did well on the check ride we flew. But the loss of control and crash on the low final turn seems like a classic “yank and bank” stall-spin.

FAA inspector Mike Puehler, a good pilot and my “boss” when I was a designated pilot examiner, made a comment at a recent meeting about practical-test failures:

“I’ve felt badly about failing an applicant when his performance was ‘almost’ OK; I’d feel a lot more badly about passing somebody on the edge and finding out they hurt or killed themselves and others in an accident.”

Was there something I missed on that check ride?

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox

![[PILOT AND SNELLEN CHART PIC]](https://www.flyingmag.com/uploads/2022/11/2022-FlyingMag.com-Native-Advertising-Main-Image--scaled.jpeg?auto=webp&auto=webp&optimize=high&quality=70&width=1440)