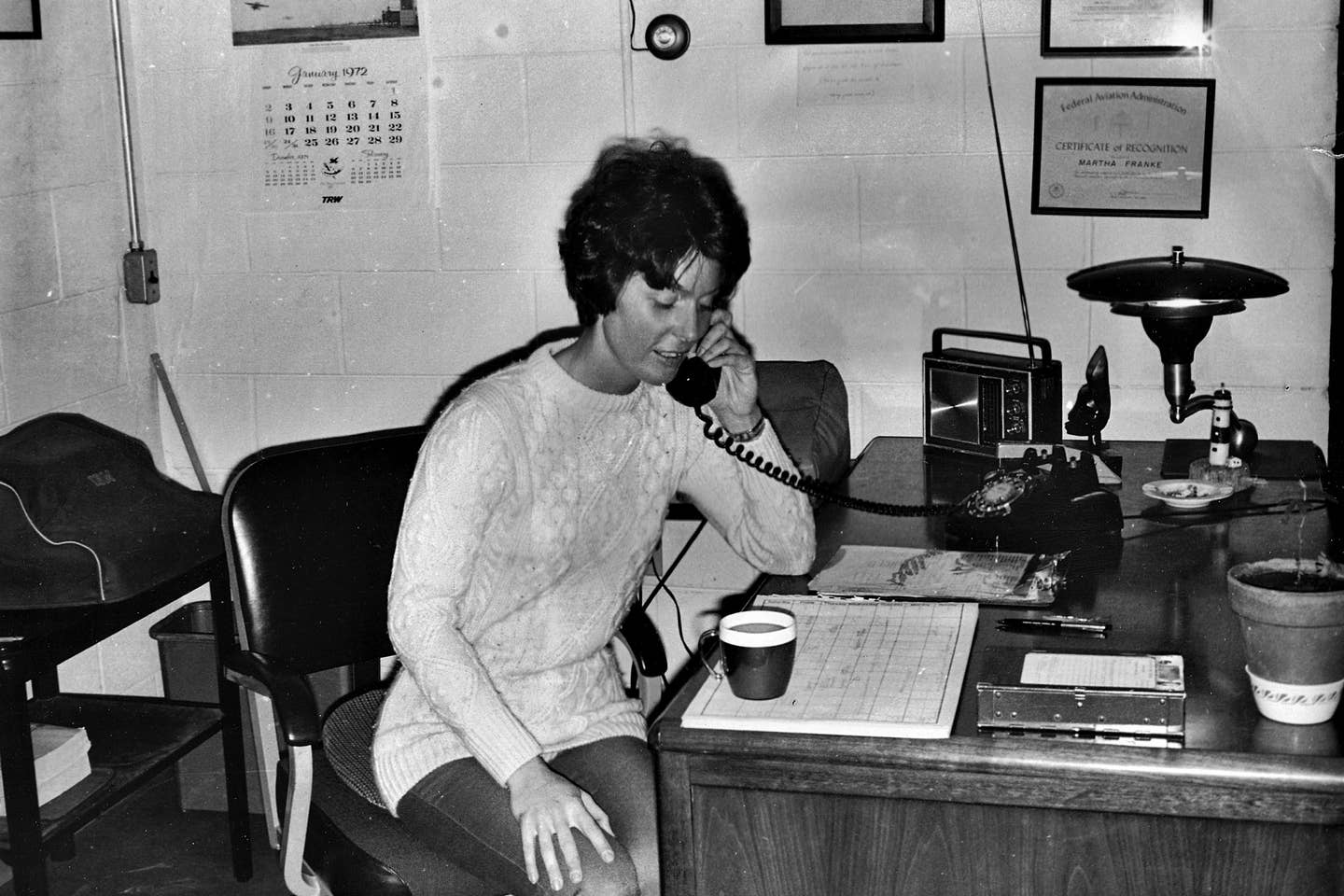

Martha in 1972 running Midwest Flight Center (aka Miss Martha’s Flying School). Courtesy Martha Lunken

OK, this is a little out of character, but last night, I “joined” (I think that’s the term) an aviation webinar—mostly because it was presented by the son of my friend Barry Schiff but also because the subject was intriguing.

Brian Schiff is an interesting guy. Longtime captain for a major airline, Brian was soloed by his famously prolific aviation dad on his 16th birthday. At heart, he has always been a GA guy who owns and flies a Citabria and is an active, accomplished flight instructor. His presentation, “SoCal Airspace Anomalies,” dissected the intricacies of navigating the challenging (to put it mildly) Southern California airspace—legally. At some time after 11 p.m., glassy-eyed and numb-brained, I left the webinar for bed. But I was so impressed with Brian’s briefing and his low-key, fun and (deceptively) casual manner as an instructor that, before climbing into the sack, I emailed father and son Schiff, “Great presentation, learned a lot…mostly, ‘Stay the hell out of SoCal airspace.’”

Not surprising, I dreamed about flight instructing that night—real and mostly sweet memories of old students and airplanes interspersed with nightmare fantasies of being a flight instructor in Southern California and headaches about the current FAA airman certification standards licensing requirements. And I remembered (yeah, here I go again), years ago, before I was a CFI, when a local flight school operator and pilot examiner named Don Fairbanks had a well-attended monthly get-together for area flight instructors. They met on the second floor of the Lunken Airport terminal building in a clubroom/bar operated, to this day (usually for something more alcoholic than education), by the Greater Cincinnati Airmen Club.

My friend Steve Grote and I were disgruntled at being excluded, but as pretty newly minted private pilots, we weren’t eligible. We were even more pissed off when an instructor friend named Carl Hilker leaned over the second-floor balcony before the meeting began, taunting us about our lack of qualification.

It was midsummer, which probably explains why Steve had a cherry bomb in his pocket. Waiting until the meeting was underway, Steve lit the firework and raised his arm to lob it over the balcony near the clubroom door. At that moment, the door to the Lunken FAA flight service station opened, and a briefer on break came out into the lobby. Steve—rather nobly, I thought—held on to the cherry bomb, and then…well, then it got pretty ugly. We retreated into the Sky Galley bar where I wrapped his hand in handkerchiefs and napkins and bought something stronger than beer. Finally, in desperation, I called his dad, a formidable, no-nonsense man who lived in nearby Hyde Park. Mr. Grote told us to get ourselves to the house while he called a doctor friend who lived next door. It was the 1960s, so this truly eminent surgeon met us in the Grote kitchen, cleaned and performed minor hand surgery, and gave Steve a bunch of meds—and both of us a piece of his mind about stupidity.

Actually, I was well on the way to having the 200 hours necessary for a commercial certificate and a CFI rating. In those days, there was no instrument-rating requirement, and in fact, the way most of us paid for that rating was by instructing. So, within three years of getting a private certificate, I was “an expert,” instructing for the princely sum of $5 an hour—and only when the meter was running.

But I did supplement my income…

See, when I had presented myself for the CFI practical test at what was then the general aviation district office, Leo Wonderly handed me his version of the oral exam—several typewritten pages of questions—and sent me back to an exam room. When I finished, we broke for lunch before flying, and out in my car, I wrote down every one of the 30 to 40 questions. With the answers, I assembled the whole thing into a book called the Flight Instructor Oral Examination Guide, which was published and sold by Sporty’s. I was no Bill Kershner, but it was a minor hit.

Read More from Martha Lunken: Unusual Attitudes

The questions covered what you’d expect: reasonable and important areas of basic instruction theory, maneuvers, techniques, records and regulations. This was in a better time—before CFIs were expected to be pseudo-psychologists, assessing a student’s personality type, teaching risk management and decision-making processes.

In the next 10 years, eventually as a multiengine and instrument CFI, I would log well over 6,000 hours. After instructing for some local schools, I bought a 1966 Cessna 150 with a loan from my dad, leased a Citabria owned by a friend (for a half-baked aerobatic course), and launched Midwest Flight Center. By teaching evening ground schools at a local university for little or nothing, I attracted enough business to keep me and several part-time instructors busy. Surprisingly, after less than a year of operation, Leo suggested “Miss Martha’s Flying Emporium” become a Part 141 school, which would eventually grant me examining authority for our 141 graduates.

Now, getting 141 school approval is usually an onerous and lengthy process with manuals to be submitted and FAA inspections conducted. But an FAA district office gets “points” for having certificated entities—Part 135, 121, 141, etc.—and in those years, the Cincinnati (then) GADO must have been low on points. We were up and running a 141 school in record time. When I voiced concern about the required manuals, Leo handed me copies of Miami University’s 141 material and said: “Just copy it—and change obvious stuff like location, layout, aircraft, etc. Submit it, and within a few weeks, you’ll get it back for corrections.”

“But why corrections when it’s identical to already-approved manuals?”

“An office never approves a manual on the first try. It will always be returned for two or three or more revisions. It’s sort of a ‘job-security’ thing. But we’ll expedite the inspection process, and you’ll be in business.”

I guess this experience, along with a few type ratings and (doubtless and probably most important) being a female, put me on the FAA’s radar as a potential employee. C’mon, there were far more guys out there with far more experience and skill begging for FAA jobs. As far back as 1970, in the very early years of the flying-school venture, they offered me an inspector position in an FAA office, but I was weighing pressures to marry Ebby. I did, but the marriage crashed and burned some years later. So, faced with instructing or starving, I applied, and they hired me—a decision they probably rued for the next 28 years.

This story appeared in the December 2020 issue of Flying Magazine

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox