The Craft of Providing Variety in Airplanes

Miles and Rutan found a way to master diversification in their designs.

In one of his books, German novelist W.G. Sebald describes the mesmerizing sight of the familiar constellations overhead. [iStock]

German novelist W.G. Sebald liked to salt his fiction with photographs. They illustrated his scenes so well that I had to wonder whether he staged the photos to match his text or shaped his story to match photos he happened to have.

In one of his books, Austerlitz, the title character goes flying at night with pilot friend Gerald Fitzpatrick in a “Cessna.” He describes the mesmerizing sight of the familiar constellations overhead. Now, looking up at the stars from an airplane is an entrancing experience, but no one ever had it in a Cessna.

If you're not already a subscriber, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today to get the issue as soon as it is released in either Print or Digital formats.

Subscribe NowThe corresponding photograph, though somewhat distant and blurred, is clearly not of a Cessna but of a small twin-engine, twin-finned airplane that does, however, have a transparent canopy. I got the explanation for this apparent authorial fumble from a Swiss friend: Among nonpilots in Germany, “Cessna” would simply mean a private airplane, no particular brand.

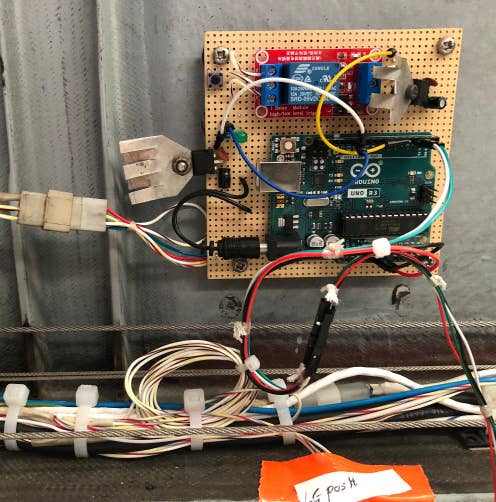

The twin was actually a Miles Gemini, an airplane brought into being, like the original Beech Bonanza, by the anticipated postwar explosion in demand for personal air travel. It had four seats and was equipped with two 100 hp engines of the inverted in-line variety, housed in those nice narrow cowlings that many British and French aircraft of the 1930s and ’40s had. One of its unusual features was a big external airfoil flap.

Despite the flap, however, the published stalling speed of 35 knots cannot have been a calibrated airspeed—45 is more plausible.

Whatever its real landing speed, the fictional Gerald Fitzpatrick crashed fatally in his Gemini. His friend Austerlitz gloomily comments that this was bound to happen, since he was so fond of making sightseeing flights in the south of France.

- READ MORE: Looking at the Physics of STOL Drag

Novelists just won’t give private planes a break.

I wondered how the 3,000-pound Gemini would do on one engine. Late designer John Thorp, contemplating a trip to Europe with his wife, Kay, once propped up a couple of small Lycomings in front of his two-seat Sky Skooter. His friend George Wing, creator of the ubiquitous Hi-Shear rivet, happened to walk in, and thus was conceived the Wing Derringer.

Wing was not taking any chances on O-235s, however. The two-seat Derringer, with 160 hp O-320s, could definitely climb on one engine. The question of how a twin with 100 hp engines climbs on only one was answered, however, by the Champion Lancer, whose woeful single-engine performance was, like Sir John Falstaff, a cause of wit in many men.

Like many other early aviation enthusiasts, Frederick George Miles began in the 1920s as an amateur builder. Miles then started manufacturing small airplanes and eventually turned out a series of products that recalls, in its variety and inventiveness, the career of another homebuilder-turned-professional, Burt Rutan. Like Rutan, who started the Rutan Aircraft Factory with his then-wife Carolyn, Miles found a business partner in his remarkable wife Maxine, nicknamed Blossom, who, in addition to being his beloved, was a pilot, aeronautical engineer, stress analyst, and businesswoman.

In some respects, the paths of Miles and Rutan were different. Miles made airplanes for military and commercial use. Rutan, after leaving the homebuilt plans business that had launched his career, mainly produced one-off prototypes and never certificated any of his designs. (Beech ruined the Starship, he complained, in the process of certificating it. Beech engineers naturally took a different view of the matter.) But the two shared a wide-ranging versatility. Some designers, like Thorp and Dick VanGrunsven, turn out incremental variations and improvements on a basic theme.

With Miles and Rutan, you never knew what might come next. In Miles’ case the variety may have been due in part to his employing other designers, whereas Rutan designed all of his airplanes himself. Both men mastered the art of fast prototyping: Scaled Composites, the company Rutan founded, exploited foam-cored composites for that purpose; Miles’ medium was resin-bonded wood.

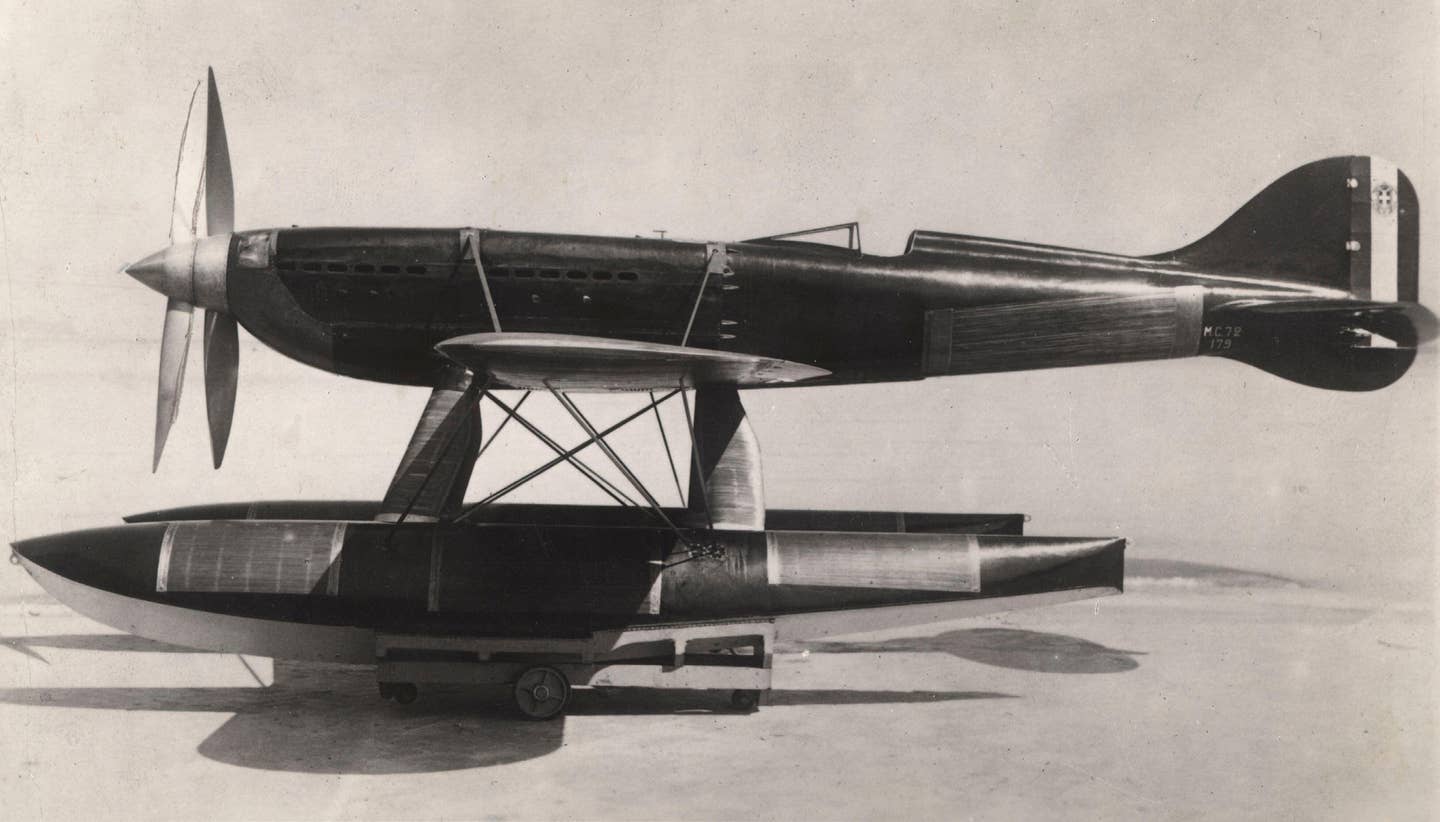

Miles’ greatest commercial success came during the pre-World War II years. He developed a number of training and transport airplanes and manufactured them in large numbers for the Royal Air Force. His efforts to produce a fighter were less successful. A 1940 prototype of a small wooden “emergency” fighter, proposed to stop the gap in the event that Hurricane and Spitfire production were hampered by German bombing, had a bubble canopy and a stock Merlin “power egg,” and looked just like a miniature Hawker Typhoon. Despite fixed landing gear, it rivaled the Hurricane in armament and performance, but it was never produced, mainly because the anticipated emergency did not materialize.

During the war, Miles produced a design remarkably similar in conception to Rutan’s first homebuilt. Like the VariViggen, Miles’ original Libellula—Latin for dragonfly—had a single pusher propeller, low wing, and high canard. The configuration was supposed to solve several problems associated with shipboard fighters, but the British Admiralty didn’t bite. A second version, this one with a high wing and low canard, was conceived as a bomber, with the idea that the tandem wing arrangement would provide an unusually large CG range. That airplane also ended up on the scrap heap.

The little Gemini twin, the one illustrated in Austerlitz, was a commercial success, as was a side venture the resourceful Miles got into: ballpoint pens. But the most striking Miles design from the wartime period was something completely different.

The M.52, born in 1943, is said to have been the offspring of a ridiculous error. An intercepted German communication referred to the 1,000 kph speed of one of the jets then being developed. Someone failed to perform the conversion, and the belief took root that the Germans were perfecting a 1,000 mph airplane. Inevitably, the British felt they needed to follow suit, and Miles Aircraft earned the contract. (If it isn’t true, at least it’s a good story.)

The result was a 5-foot-diameter cylinder with thin, straight wings and a then-unprecedented, and prescient, powered all-flying stabilizer. Air for its centrifugal-compressor jet engine came in through an annular intake surrounding a shock cone, à la the MiG-17 or SR-71. The pilot sat inside the shock cone. In retrospect, the design looks sound except for its lack of area ruling, and it could probably have gone supersonic, given sufficient thrust. But in 1946, with the first prototype nearly complete, the U.K.’s Air Ministry suddenly canceled the project.

The abrupt cancellation, which was never persuasively explained, fueled a persistent notion among British airplane buffs that their government had abjectly bowed to U.S. insistence on being the first to “break the sound barrier.” Indeed, the Bell X-1 rocket aircraft, which did so in 1947, was being developed at the same time as the M.52.

However, the M.52 may have been shelved simply because of the distinct possibility that its still-unproven afterburning turbojet might not be powerful enough to propel it past Mach 1 in level flight—let alone to 1,000 mph.

This column first appeared in the May 2024/Issue 948 of FLYING’s print edition.

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox