Understanding Tach and Hobbs Meter Numbers

These figures are critical for determining when aircraft inspections are due and how much to bill for a flight.

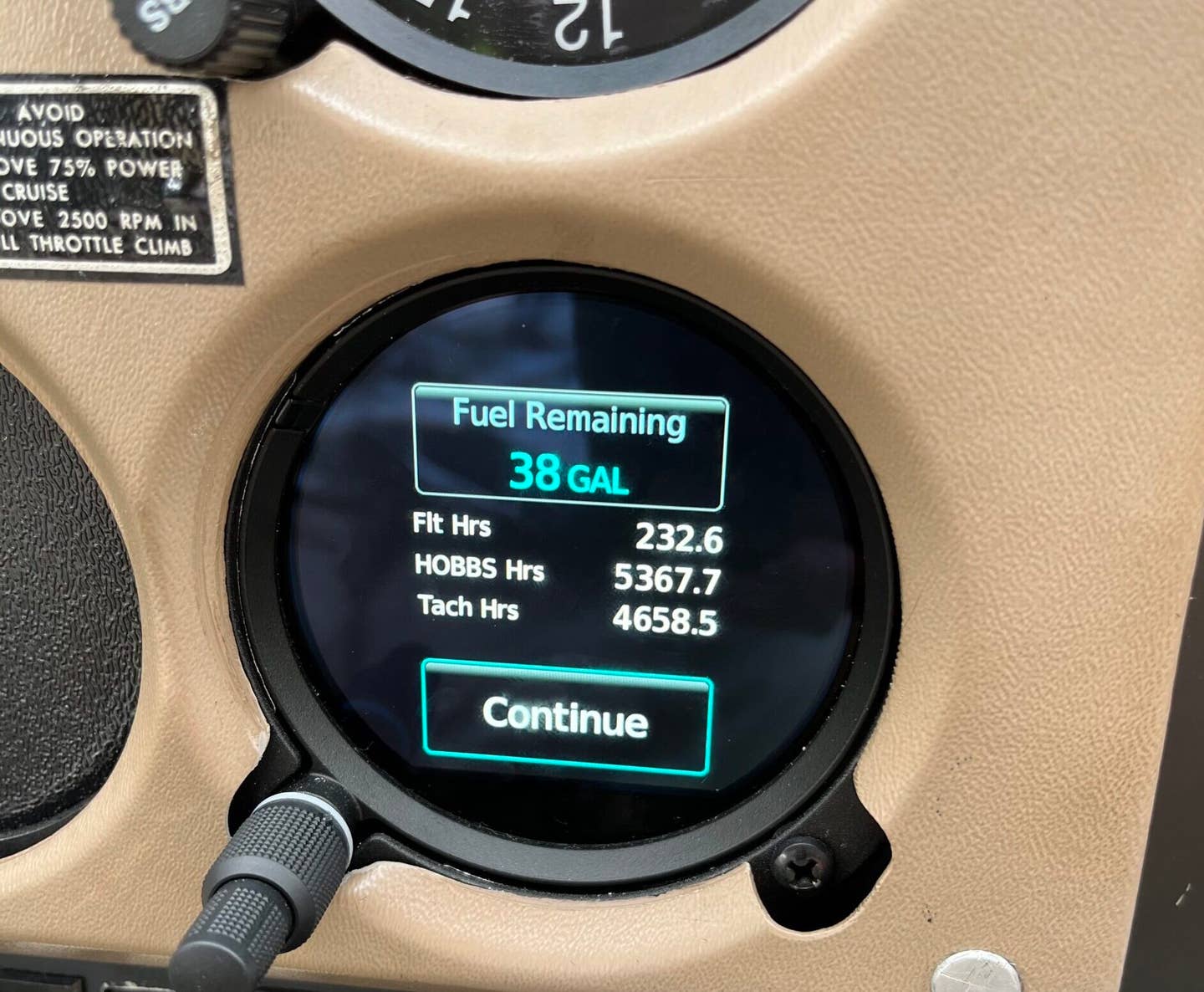

Tach and Hobbs meter numbers are critical for determining when certain aircraft inspections are due, when airworthiness directives need to be complied with, and how much the customer will be billed for the flight. [Credit: Meg Godlewski]

"Did you check the tach and the Hobbs numbers?"

I wish I had a dollar for every time I was asked this, or asked someone else this. These numbers are critical for determining when certain aircraft inspections are due, when airworthiness directives (ADs) need to be complied with, and how much the customer will be billed for the flight.

Yet, there are pilots who do not do even a perfunctory review of this information before a flight, such as looking in the dispatch sheet and comparing it to the instruments in the airplane, or vice versa. It can come back to bite you, especially if the flight school is very busy and the person who handles the aircraft dispatching gets rushed and numbers are copied down incorrectly.

Pilots may even end up paying for someone else’s flight time—or a portion of it, or worse, accidentally overfly an inspection or an AD. The latter can result in a slap on the wrist from the FAA or sanctions from the flight school, or both.

Hobbs Versus Tach Time

The Hobbs meter measures time in tenths of an hour. This is the one you want to pay attention to because it is where you get the time that goes into your logbook, along with how much you are billed for the flight. The tach determines the maintenance items such as the ADs and 100-hour inspections.

The Hobbs meter, like anything mechanical, can fail. I worked at a flight school where the Hobbs was tied to the aircraft master switch, and for reasons never explained to the CFIs, it failed at an alarming rate and in multiple aircraft.

In simplistic terms, the tachometer measures engine time. It can vary depending on how fast the engine runs, and is an approximation of time in service. The faster the rpm (more power), the higher the tach reading.

According to several mechanics I asked about this, the tachometer time is usually 20 percent below that of the Hobbs. That would mean that if the Hobbs reading indicates a flight of 1.0, the tach would indicate 0.8 of an hour. Given this nugget of knowledge, when the Hobbs failed, we multiplied the tach to get the "billable" time.

Juggling Maintenance Times

Operating a flight school with multiple airplanes can often be a juggling act. While the calendar determines the bulk of the required inspections, the ADs and 100-hour inspections are triggered by the tach meter readings.

Running out of airplanes due to airplane timing out can really impact the bottom line, and it happens at the busier schools where the CFIs are racking up 40 hours of flight time a week.

For this reason, many flight schools have software that flags an aircraft "coming due," and the school does its best to stagger the time-required inspections, operating around the workload of the maintenance team.

Some flight schools have a rule that if an aircraft is within 0.8 of the 100-hour or an AD coming due, it is grounded and removed from the rental fleet. Often there is a story behind it, like someone accidentally overflew something.

At my favorite flight school, the boss had a rule that if the aircraft was within 1.0 of inspection or an AD and there was no one on the schedule, a CFI was handed the keys and instructed to go out and fly approaches for proficiency until the aircraft was "timed out" so it could get into maintenance. The CFI logged coveted solo time and didn’t have to pay for it.

The 100-Hour Question

Here's a question often asked on check rides: If the airplane is still in annual but past the required 100-hour inspection and requires a 100-inspection because it is used at a flight school for training and scenic flights, can a pilot who is not being paid for the flight legally take the airplane into the pattern for a currency flight?

- READ MORE: The Art of the Subgoal

It appears the answer is yes, according to cFAR 91.409, which states "no person may operate an aircraft carrying any person (other than a crewmember) for hire, and no person may give flight instruction for hire in an aircraft which that person provides, unless within the preceding 100 hours of time in service the aircraft has received an annual or 100-hour inspection and been approved for return to service in accordance with Part 43 of this chapter or has received an inspection for the issuance of an airworthiness certificate in accordance with Part 21 of this chapter." There is no reference to single-pilot operations.

Provided the aircraft was not overflying any ADs (check those numbers!), flying could take place.

More Helpful Tools for Flight Training

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox