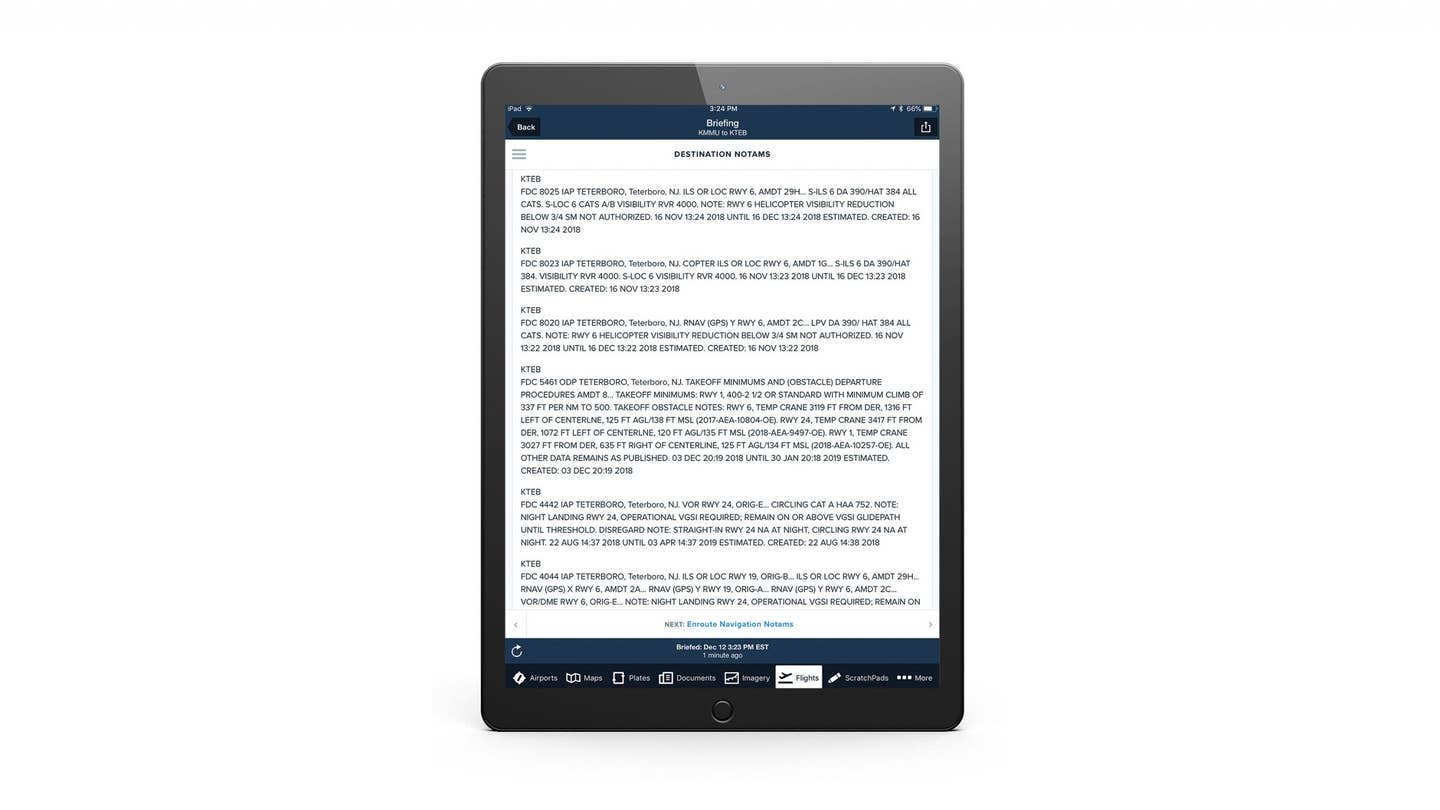

An example of a page of typical notam gibberish on an iPad that many experts believe compromises safety. Flying

"That’s what notams are. They are just a bunch of garbage that nobody pays any attention to.” It would be a dramatic statement regardless of who said it. But this was Robert Sumwalt, chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, speaking at a hearing.

Sumwalt had reason to be upset. An Air Canada jetliner had come within 13 feet of another airliner on a go-around after having made an approach to Taxiway Charlie at San Francisco International Airport instead of Runway 28R. The left runway was not illuminated, because it was closed. The pilots lined up with the right of the two remaining sets of lights.

The frustrating part is the notice to airmen (notam) system is in place to help prevent exactly this kind of mistake. And the pilots did have a warning of the closure — on page 8 of their 27-page notam report.

People who design cockpits have picked up on the need to guard against information overload. If there is a light or horn to warn about everything, then nothing stands out. It is the same as if there were no warnings at all. A first step in notam reform would be to review whether having fewer, more impactful notams might actually be an improvement in risk management.

Sumwalt isn’t the first person to complain about notams. After Oklahoma Sen. James Inhofe landed on a closed runway, he said that while “technically” pilots should “probably” check notams, it would be impractical for him to do so on the many flights he makes to small airports in Oklahoma each year. “People who fly a lot just don’t do it,” Inhofe told the Tulsa World.

His complaint was that notams should be more accessible and easier to find. So, after his experience, Inhofe championed the 2012 Pilot’s Bill of Rights. Included in its many provisions was a requirement for the “notam improvement panel,” which, among other things, created an online search tool to help pilots find notams. But the tool is clunky to use, and the FAA won’t allow you to use it until you have agreed not to make it your only briefing.

The FAA doesn’t consider the tool to be a “complete and accurate source.” The FAA wants you to contact Flight Service instead. So, Inhofe included a provision in last year’s FAA Reauthorization Act that all notams be posted in a publicly available, central online forum.

But there is another problem with notams. They appear to be written to serve the government rather than the reader. They often lead off with legalese stating their authority to place restrictions on airspace and the penalties for violation. We recently had an airshow at a nearby military field that closed our local airport intermittently. The FAA issued two separate notams that had to be looked at together to understand the closure times. That, plus the usual coded format, made them a real struggle to understand.

Of course, each notam started out by stating their legal authority for the airspace closure in all caps. Then, like all notams, they continued in the standard notam language only a computer programmer could love. First, they gave the closed area as a radius around a latitude and longitude (backed up by the seven-digit coded reference to a direction and distance from a vortac).

Next, they stated the date and Greenwich Mean Times (GMT) of the beginning and end of the time periods, each coded with six digits. Each notam continued in all caps with three ungrammatical nonsentences to describe the purpose of the closure, and to state the rules.

They finished with the telephone number of the “CDN facility” and the available hours, again using those six-digit date and time codes.

I had no idea what a CDN facility was, so I called the number to ask them what it meant. The person answering the phone didn’t know either. After about a 20-minute web search, he reported that CDN stood for “coordination facility.”

The fact that notams are extremely difficult to read once they do get in the hands of pilots is perhaps the biggest problem of all. The style stems from the 1850s, when communications were slow and expensive. It violates virtually every principle of good readability.

To reduce the number of keys needed on the teletype machines of the time, they used all caps, which, due to their uniform, blocklike shape, are difficult to tell apart from each other. Plus, to save space they used codes and abbreviations. All of this might have made sense in the 1800s, but today, in the age of huge bandwidths and practically free communications technology, there is absolutely no excuse for it.

Being stuck in the 1800s also means that notams don’t make use of the many very basic tools that the rest of the world uses routinely to make our written communications user-friendly. Even something so simple as varying type fonts and headlines to show the organization of a communication helps make understanding much easier. Plus, of course, with the availability of images that can easily be captured and displayed on our handheld devices, there is no reason not to back up a description with a graphic every now and then.

With the availability of computers, we should go even further and adopt “smart” notams. If a runway is closed, the system should, at a minimum, tell me about the runway closure before it tells me about the rest of the implications, such as the localizer, glideslope and lights all being out of service — if it tells me about them at all.

Another feature of smart notams might be to give me information grouped in the context of how I will use it. There are some notams that would only be important in instrument or night conditions. If I am going to fly on a daytime VFR trip, an unlighted tower 3 miles away wouldn’t hold a high probability of being a problem.

Considering the importance of their messages, notams should be the ultimate in accessibility, readability and ease of use. In the rest of our lives, the tools we all use on a daily basis — the internet, cellphones, tablets, digital maps — are improving continuously. The fact that notams have remained so substandard in this era reflects profound indifference and is a breach of faith and trust.

The great strides being made by commercial flight planning programs are largely compensating for this abject failure, but it is the government’s responsibility to get this right in the first place. It’s time for the folks who run the program to demonstrate they have the interest of pilots at heart. No longer should notams be, as Sumwalt says, “just a bunch of garbage that nobody pays any attention to.”

Sign-up for newsletters & special offers!

Get the latest FLYING stories & special offers delivered directly to your inbox